David Cote

David Cote

In Will Arbery’s play, four characters in a Texas town walk the line of mourning, redemption, and weirdness.

Deirdre O’Connell as Justice, Will Dagger as Christopher, and Jamie Brewer as Ginny in Corsicana. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

Corsicana, by Will Arbery, directed by Sam Gold, Playwrights Horizons, 416 West Forty-Second Street, New York City, through July 10, 2022

• • •

Accepting the Best Actress Tony Award two weeks ago for playing a terrorized yet sympathetic hostage in Dana H., Deirdre O’Connell stumped for the strange. “Should I be trying to make something that could work on Broadway?” the veteran performer rhetorically queried in her speech. “Or should I be making the weird art that is haunting me, that frightens me, that I don’t know how to make, that I don’t know if anyone in the whole world will understand?” Her conclusion: “Make the weird art.”

Deirdre O’Connell as Justice in Corsicana. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

A couple days after the ceremony, O’Connell returned to the Land of Odd in Will Arbery’s Corsicana as Justice, a kindly librarian dreaming of a dead, benevolent stranger. Justice is one in a quartet of static pilgrims in Arbery’s diaphanous murmur of a play, named after the small Texas city, lightly dusted with its lore, and obsessed with notions of community and gifts. The other figures scotch-taped to this sere and desolate landscape are Christopher (Will Dagger), a depressive thirty-three-year-old film teacher; his older half-sister, Ginny (Jamie Brewer), who has Down syndrome; and Lot (Harold Surratt), a stone-faced recluse who makes found-art sculpture and songs. Ironically, O’Connell-as-Justice is the least conventionally weird element in Corsicana, staged with pronounced aridity and earnestness by Sam Gold. She’s warm, endearingly off-kilter, doggedly loyal to friends. The production around O’Connell, though, strains for its bizarre reverberations.

Jamie Brewer as Ginny and Will Dagger as Christopher in Corsicana. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

In the past decade, “weird” has become shorthand among reviewers for non-naturalistic work that doesn’t fit historic slots such as Surrealism, absurdism, or Expressionism (although it grows on their graves). New York critic (and past 4Columns contributor) Helen Shaw has written most eloquently about the slippery genre, in which “we find elements of the Lovecraftian uncanny—whether in pursuit of delight and wonder . . . or as a way to convey a kind of metaphysical terror.” Weird dramaturgy may use realism, as a parasite uses a host, to achieve shivery effects or plunge audiences into a world of ghosts, codes, or ritual. The weird’s Euro-American genealogy includes Strindberg, Pinter, and Albee, all the way up to Mac Wellman and the generation inspired by his neo-Dada lingo tricks.

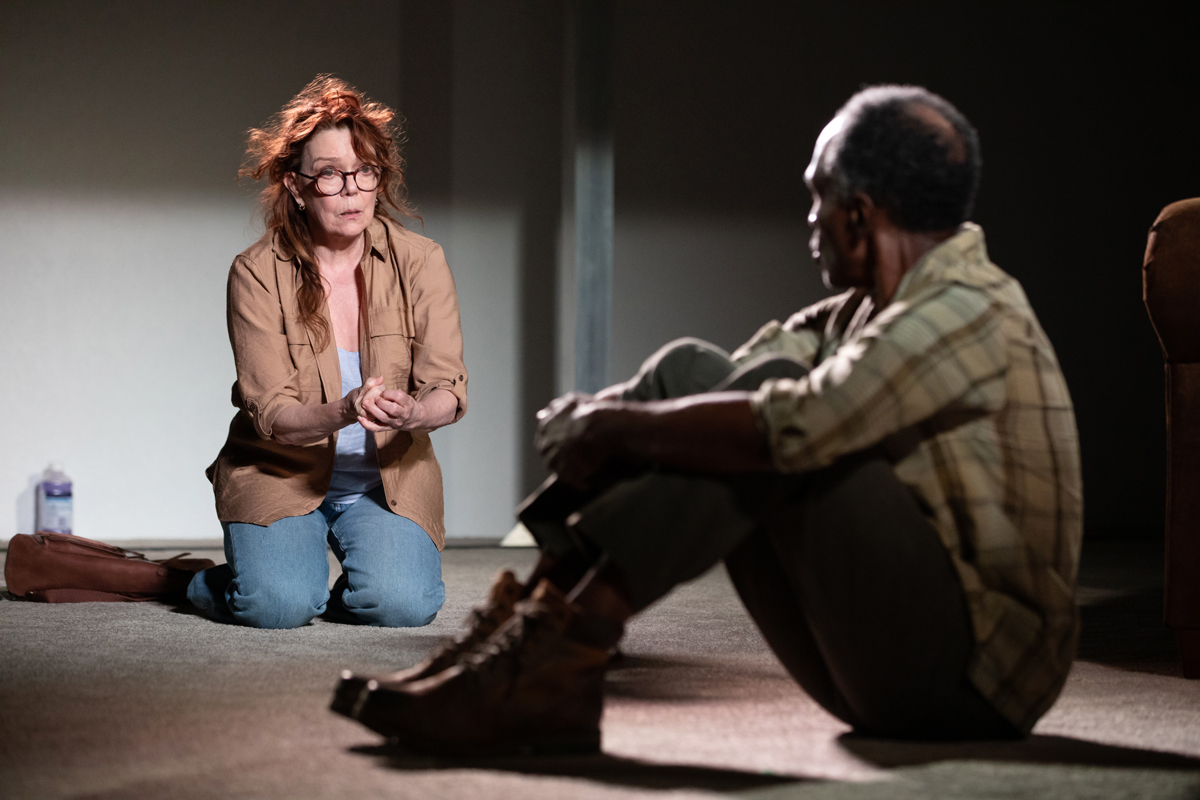

Deirdre O’Connell as Justice and Harold Surratt as Lot in Corsicana. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

The word itself pops up in Corsicana about two dozen times. Lot says Justice is weird. Justice playfully calls Lot “weirdo.” Lot pens a song called “Weird.” “Weird” is how Ginny describes Lot’s bluesy croon. Such aggressive (excessive?) patterning may be Arbery signaling his awareness of the discourse around his theatrical niche, staying on-brand. But while weird can be fairly specific when used by critics, in the mouths of characters it accrues vagueness, a groping for mysteries beyond understanding. Much of Arbery’s dialogue evinces awkwardness or wariness, lousy with fidgety fillers: like, um, or uh. “I’ve been testing the idea that language is inherently always a bit of a lie or a compromise,” the playwright said in a talk with the Paris Review. Conversation is dust subject to the winds of confusion, as in this early exchange between Christopher and Lot:

CHRISTOPHER: Okay right uh—my name is Christopher and I was wondering if you’d want to um—if you were in the position to—like if you were looking for—I was wondering if I could give you a little work?

LOT: Your work?

CHRISTOPHER: What?

LOT: Work you made? You want to give it to me?

CHRISTOPHER: Oh—no—what I meant was I was wondering if I could, like, employ you.

Such deadpan negotiation would not be out of place in a Richard Maxwell piece circa 2005. As Christopher, Dagger has the runty, hangdog appeal of a young Harry Dean Stanton, and Surratt’s stiff-jointed as Lot, a character who probably lives on the autism spectrum. Their energy mismatch—Christopher’s nervous politeness, Lot’s dour literalism—has a gently comical effect.

Harold Surratt as Lot in Corsicana. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

Christopher and Ginny have been mourning the loss of their mother, and the brother thinks Ginny would be cheered by writing a song in collaboration with Lot. The folk artist has risen in local prominence due to a magazine profile arranged by Justice, who realizes (too late) she has a crush on Lot and might have exploited him for her own ends. Ginny and Lot meet a couple of times to discuss the song, and between her sweet but circumscribed behavior and his recessive personality, they both repel and attract each other. When Ginny talks about a fourteen-year-old “boyfriend” (she’s thirty-four), Lot suffers a panic attack, which gets worse when Ginny mentions inappropriate touching in her past. As an adolescent, Lot had a traumatic experience with special-needs classes and an intimate friendship that attracted the attention of the police.

Will Dagger as Christopher in Corsicana. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

These narrative bones have the making of a Texas gothic about disability and small-town intolerance, but Corsicana takes an emo-minimalist tack: two-and-a-half hours of candid, if halting, conversations in kitchens, living rooms, and Lot’s art-strewn house. We never see his work. At the top and bottom of the play, Surratt laboriously opens and closes Lot’s “gate”—the upstage-right intersection of adobe-like walls designed by Laura Jellinek and Cate McCrea.

Everyone here has one foot in reality and the other in a liminal zone of grieving, dreaming, or spirit-watching. “I’ve been desperate for a numinous experience,” Justice says apropos of Christopher describing a trip on ’shrooms. Justice communes at the dinner table with her deceased friend, an unnamed dead man, and her own future shade; Lot can scent questions in the air and knows that dinosaur ghosts walk the streets of Corsicana. Christopher has a sprawling, second-act monologue about making peace with his bullying father and passive mother that features a postal worker who may be an angel. The play is capacious, winding, sometimes frustrating in its simultaneous tweeness and profundity. (By contrast, Arbery’s 2019 Catholic-right talkfest Heroes of the Fourth Turning was a perfectly proportioned and brutally coherent vision of spirituality imposed on the social.)

Jamie Brewer as Ginny in Corsicana. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

Providing relief from the mystical fug of specters and omens, Brewer’s Ginny is a clarifying agent: a Zac Efron–infatuated imp, her bright fuchsia leggings a defiant splash of color against the muted earth tones of the rest of the ensemble (costumes by Qween Jean). Ginny can be bratty, mean, wise, or funny, and the integration of this unique actor with the rest of the cast is quite organic and convincing. As ever, the nervy O’Connell finds endless variations on empathic wryness to create another portrait of battered but unsinkable womanhood.

The play’s a bit of a slow cooker into which Arbery dumped several obsessions: his relationship to a real-life sister with Down syndrome, how a failed utopia is like a family, gift economies versus monetary transactions, and his habitual fascination with ghosts and topography. The ending (a bit too drawn out) comes with a group sing-along, each character warbling their woes away. The finale a song of redemption. Nothing very weird about that.

David Cote is a theater critic, playwright, and librettist based in Manhattan. He reviews theater for Observer. His work has been produced in New York, Cincinnati, Chicago, and London.