Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

In an exhibition of twelve artists reflecting on the Great Migration, a distinctively Black-centered gaze.

A Movement in Every Direction: Legacies of the Great Migration, installation view. Photo: Mitro Hood. Pictured, left on back wall: Mark Bradford, 500, 2022; center foreground: Torkwase Dyson, Way Over There Inside Me (A Festival of Inches), 2022.

A Movement in Every Direction: Legacies of the Great Migration, curated by Jessica Bell Brown and Ryan N. Dennis, Baltimore Museum of Art, 10 Art Museum Drive, Baltimore, Maryland, through January 29, 2023

• • •

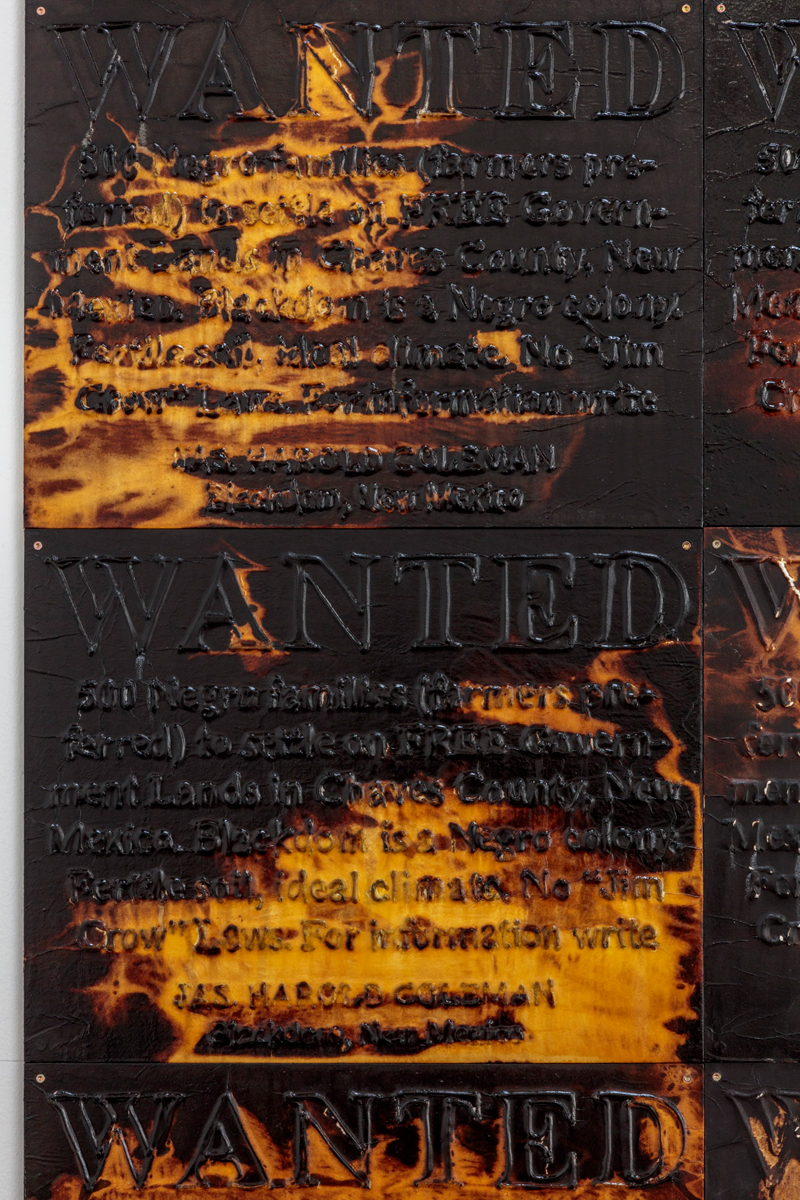

One of the first works you see upon entering A Movement in Every Direction: Legacies of the Great Migration is a large wall-mounted piece by Mark Bradford titled 500 (2022). Each of its sixty panels is embossed with text, part of which reads: “WANTED 500 Negro families (farmers preferred) to settle on FREE Government Lands in Chaves County, New Mexico. Blackdom is a Negro colony. Fertile soil, ideal climate. No ‘Jim Crow’ Laws. . . .” (The lines are reproduced from an advertisement that appeared in a 1913 issue of the NAACP’s quarterly magazine, The Crisis, where such postings were common throughout the early twentieth century.) The word wanted is larger than the rest, all in capital letters, evoking both threat (think of posters identifying hunted Black men, from those escaping enslavement to those fleeing from often unjust laws) and desire (don’t we all want to live on fertile soil in an ideal climate?). The panels are colored with browns and golds and yellows, as if they were remnants of a fire—one by turns destructive and purifying.

Mark Bradford, 500, 2022 (detail). Mixed media on panel. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Joshua White. © Mark Bradford.

The painting encapsulates many of the ideas that run through this ambitious show, organized by Ryan N. Dennis of the Mississippi Museum of Art (where the exhibition made its debut) and Jessica Bell Brown of the Baltimore Museum of Art. The curators commissioned twelve artists to conceive works that reflect on the Great Migration, a period lasting from the 1910s to 1970, which saw six million African Americans move from Southern states to the North, Midwest, and West, and from rural existences to urban ones. (Prior to 1910, over ninety percent of Black Americans lived in the South; by 1970, just over fifty percent did.) As suggested in Bradford’s 500, the movement was spurred by multiple factors, including both the oppressive (economic privation, environmental disasters, and racist violence) and the hopeful (the promise of better paying jobs and new, more peaceful lives).

The invited artists were encouraged to think about the historical event in terms of their own family chronicles and movements, a maneuver that makes the show feel deeply intimate. The curatorial focus on the personal has another important consequence: there is only occasional reference to the white-perpetrated violence and injustices that triggered such an exodus—the focus of the exhibition is foremost on the agency of those who left and those who stayed in place. White supremacy is a given, but it’s not the story.

Akea Brionne, An Ode to (You)’all, 2022. Jacquard tapestry, Poly-Fil, rhinestones. Photo: Mitro Hood.

The resulting works, all from 2022, vary in form and approach. Portraiture, not surprisingly, has a strong presence. In her series An Ode to (You)’all, Akea Brionne has woven six jacquard tapestries based on photographs of her great-grandmother and great-aunts who remained in Mississippi so that the menfolk could move North and ensure prosperity for future generations; she has sewn delicate rhinestone haloes around the heads of the relatives who appear in some of the snapshots and has reverentially adorned the women’s skirts. Robert Pruitt’s affectionately funny, mural-size drawing A Song for Travelers likewise starts with a family photo—of a family reunion—in which he has replaced the figures, some with his own ancestors and others with archetypes from generations of Black communities that prospered in Houston, where the artist grew up: a soldier (a reference to Houston’s 1917 Camp Logan uprising), a female high school athlete, church ladies of various eras, his grandfather, who wears a Mason’s hat, and his mother in her beauty-queen era. The seated figure in the foreground of the composition, wearing a strange Afrofuturist mash-up of a robotic suit of armor topped by a traditional African American face jug, is a traveler—a stand-in for Pruitt himself.

Robert Pruitt, A Song for Travelers, 2022. Charcoal, conté crayon, and pastel on paper mounted on aluminum. Photo: Mitro Hood.

But there is also conceptualism. Torkwase Dyson’s Way Over There Inside Me (A Festival of Inches) is a dynamic, abstract construction whose forms derive in part from her study of the blueprints for Tougaloo College, a historically Black institution near Jackson, Mississippi. Four smoked-glass enclosures are connected by steel joists that rise, descend, and turn corners, creating indirect routes toward those provisional places of safety. Leslie Hewitt’s three related untitled sculptures, which appear in different galleries, consist of hot-rolled steel beams laid on the floor at right angles with curved red-oak shapes and vintage glassware positioned carefully within the space they delineate. (The placement of those beams was inspired by the floor plan of Hewitt’s grandmother’s house in Macon, Georgia, which also served as an upholstery shop and a grocery store.)

Leslie Hewitt, Untitled (Slow Drag, Barely Moving, Imperceptible), 2022. Hot-rolled steel, red oak, inherited glass objects. Photo: Mitro Hood.

Landscape plays an important role in the show—not only in terms of histories of dispossession and the effects of climate change, both of which drove people from the South, but as a sign of longing for origins. An extraordinary three-channel film installation by Allison Janae Hamilton titled A House Called Florida takes us to Apalachicola Bay and the Blackwater Lakes of Florida’s Big Bend, suggesting the ways that the South—its rivers, forests, homes, roadways—is both shaped and haunted by the past. Permanent Change of Station by Zoë Charlton complicates the idea of starting point and destination by reminding us that the military—no less than factories up north—offered opportunities for economic mobility to those in the South, including generations of her own family. Her installation includes a large drawing of a woman in military dress looking out over a verdant landscape that ranges from Florida’s Spanish moss to Southeast Asian rice paddies, flora from the multiple global sites where she and her family have been stationed. Arranged in front of the drawing are rows of standing wood panels collaged with images of foliage culled from craft-store sticker books (the effect is something like a children’s pop-up book); tucked within the leaves is a representation of her grandmother’s Tallahassee bungalow, which was lost to foreclosure, and Thomas Kinkade bungalows—two very different dreams of home.

Zöe Charlton, Permanent Change of Station, 2022. Collage on wood panel, graphite, gouache, and collage on paper. Photo: Mitro Hood.

In addition to removing whiteness from its curatorial conception, other subtle strategies also demonstrate the exhibition team’s refreshing and even radical approach. Look closely—at the wall texts, at the handsome booklet that is free for visitors to take away, and at a digital storytelling booth tucked in one of the galleries—and you will realize that the assumed viewer is Black, or at least is someone whose life has been inflected by the Great Migration. “We hope this exhibition inspires a profound sense of possibility for you, especially in the reflection upon your own family histories and the way those legacies move through the present and guide towards the future,” says the opening wall text. In the digital storytelling booth, visitors are welcomed to share tales of their “roots and routes,” which will be available on Greatmigrationlegacies.org during the exhibition’s run. (Importantly, the exercise is not an extractive one of building an archive out of individuals’ family lore—at the end of A Movement’s tour, those who contributed stories will be sent their digital files to do with as they please, and the online platform will be shut down.)

Allison Janae Hamilton, A House Called Florida, 2022. Three-channel film installation, color with sound, 34 minutes 46 seconds. Photo: Mitro Hood.

The show, that is to say, is not organized around the white gaze. It doesn’t offer up Black history as an object to be consumed by hungry visitors but rather as a process of thoughtful creation, over time, in and for community. That this can happen at a predominantly white institution like the Baltimore Museum of Art—whose visitor demographics do not reflect the fact that the city is sixty-four percent Black—is an important intervention, both for the poetry it produces as well as for its consequential shifting of the museum to a more and truly public mission.

Aruna D’Souza is the 2022–23 W. W. Corcoran Professor of Social Engagement at the Corcoran School of Art and Design in Washington, DC and a contributor to the New York Times and 4Columns. She was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.