Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

An empathetic lens: the Whitney Museum hosts a retrospective of the photographer’s career.

Dawoud Bey, Untitled #1 (Picket Fence and Farmhouse), from Night Coming Tenderly, Black, 2017. Gelatin silver print, 48 × 55 inches. © Dawoud Bey.

Dawoud Bey: An American Project, curated by Elisabeth Sherman and Corey Keller, Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York City, through October 3, 2021

• • •

In 2017, Dawoud Bey created a series of velvety, shadowy photographs of the sites and routes in Ohio that people likely traveled to flee enslavement—elusive, sometimes imagined, traces of the Underground Railroad. He called it Night Coming Tenderly, Black. These nighttime images are made from the point of view of those trying to escape unimaginable horrors, for whom darkness was a form of safety and protection. The series’ title comes from a poem by Langston Hughes, “Dream Variation” (1926), in which the poet imagines a world in which he is both free “To fling my arms wide / In some place of the sun, / To whirl and to dance / Till the white day is done,” and later to find comfort in the “Night coming tenderly / Black like me.”

Dawoud Bey: An American Project, installation view. Photo: Ron Amstutz. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art.

The full quotation of the verse seems crucial when looking at the work of this MacArthur-winning artist and educator, who is the subject of a career-spanning, traveling retrospective, Dawoud Bey: An American Project, which originated at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and is currently on view at the Whitney Museum. The show, the majority of which is installed on the Whitney’s eighth floor, is organized around eight major series, created from the mid-1970s to today, that depict Black life in cities and landscapes, make connections between history and the present, and give visual space to those who most often go unseen and unrecognized. In all of these photographs, the two words from Hughes’s poem that Bey leaves out of his title, “like me,” seem to hover in the background nevertheless. The deep empathy that Bey cultivates in his work feels like an act of self-definition, and, touchingly, of self-love.

Dawoud Bey, Four Children at Lenox Avenue, from Harlem, U.S.A., Harlem, NY, 1977. Gelatin silver print, 11 × 14 inches. Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, Stephen Daiter Gallery, and Rena Bransten Gallery. © Dawoud Bey.

Though he grew up in Queens, Bey and his family had extensive ties to Harlem. In 1975, shortly before he turned twenty-two, he took his 35mm camera and started photographing life in that neighborhood. He had both positive models to emulate—Roy DeCarava, James Van Der Zee, even the largely anonymous photographers whose work was featured in Harlem on My Mind, the controversial 1969 exhibition at the Met that made a deep impression on him—and negative ones. In an excellent video interview on the Whitney Museum’s website, Bey talks about wanting his series Harlem, U.S.A. (1975–79) to stand “in relation to the more . . . pathologically driven representations of African Americans.” He refers here, I presume, to depictions that focused on what was wrong with Black communities, motivated by activist desires to promote change or by racist stereotyping. The people in Bey’s gelatin silver prints—whether they are caught unawares, like the schoolgirls in Four Children at Lenox Avenue, or pose flamboyantly for the camera, like the youngsters in Two Girls at Lady D’s—don’t need your help or your pity. All Bey’s Harlem subjects take up space, command it, even, thanks in part to their own composure and in part to the photographer’s careful framing and respectful distance.

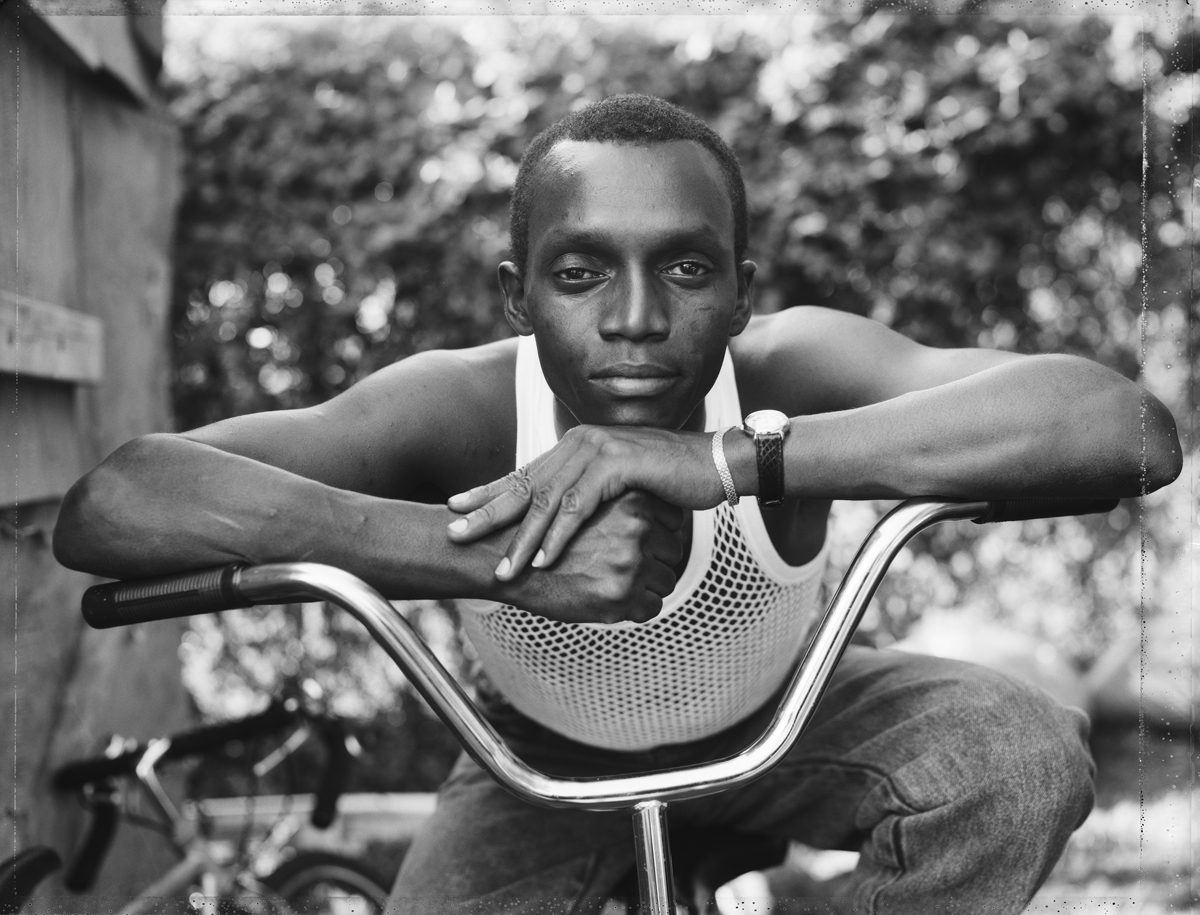

Dawoud Bey, A Young Man Resting on an Exercise Bike, from Type 55 Polaroid Street Portraits, Amityville, NY, 1988. Pigmented inkjet print, 30 × 40 inches. Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, Stephen Daiter Gallery, and Rena Bransten Gallery. © Dawoud Bey.

Bey’s early forays into candid street photography—Harlem U.S.A. and the 1985 suite of photos Syracuse, NY, made during a residency at Light Work, a storied artist-run nonprofit there—quickly morphed into street portraiture. Bey began to develop a more transparent relationship with his subjects, allowing them the opportunity to decide on their own self-presentation. In 1988, this led him to set aside his handheld camera and adopt a tripod-mounted 4×5-inch-format camera for his Type 55 Polaroid Street Portraits, taken in Brooklyn; Washington, DC; Amityville; and other places. The results are extraordinary. The arms and shoulders of the relaxed but alert adolescent in A Young Man Resting on an Exercise Bike (1988) echo perfectly the curved cycle handles on which he leans. The teen in A Girl with a Knife Nosepin (1990)—despite the bad-assery of her jewelry—gazes vulnerably at us, looking even more a child than her apparent age, while the subject of A Young Woman between Carrollsburg Place and Half Street stands in a bold contrapposto, arm akimbo, looking confident and poised.

Dawoud Bey, A Girl with a Knife Nosepin, from Type 55 Polaroid Street Portraits, Brooklyn, NY, 1990. Pigmented inkjet print, 40 × 30 inches. Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, Stephen Daiter Gallery, and Rena Bransten Gallery. © Dawoud Bey.

Bey would have been almost ten years old on September 15, 1963, when the Ku Klux Klan bombed the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four Black girls; racists murdered two Black boys later in the day. He was just shy of sixty when he went to that city to commemorate Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley, Johnny Robinson, and Virgil Ware half a century later. The result of his visit, and others that followed, was The Birmingham Project. (The piece is installed in the street-level gallery of the Whitney, free to the public; it is a suitably chapel-like space for the paired, black-and-white inkjet prints and the video, 9.15.63, that accompanies them.) Bey’s strategy for marking the horror is to understand it in the most human terms possible. By creating diptych images of children who were the ages of the six victims paired with images of people of the ages the victims would be had they survived, history is turned into a bodily experience, measured by his, and our own, sense of aging and mortality. The Birmingham Project thus evokes an almost visceral comprehension of what was lost and what could have been.

Dawoud Bey, Mathis Menefee and Cassandra Griffin, from The Birmingham Project, 2012. Pigmented inkjet prints, each 40 × 32 inches. © Dawoud Bey.

In a quietly brilliant curatorial move, Harlem, U.S.A. is not the first thing you encounter in the otherwise chronologically organized eighth-floor galleries. Hung on the walls to either side of the entrance is Harlem Redux, a series that Bey began in 2014 to highlight the ways in which the neighborhood, like so many in our cities, has changed under the pressure of global capitalism and the gentrification that results. These are not the portraits for which Bey is so famous—the community that had found favor with his camera in the past has been significantly diminished, replaced by well-to-do white professionals priced out of other parts of the city and the new upscale businesses that follow their money and taste. Using a medium-format camera and color film to emphasize the contemporaneity of the photos, he pictures ruins, like the Lenox Lounge, and construction sites. When people appear, they are anonymous and shot unawares, like the white man who sits at a sidewalk café oblivious of his surroundings, or the tourists—including a white man whose disembodied arm leans against a tree centered in the frame, functioning as a visual and literal barrier—who stand across the street from the Abyssinian Baptist Church, obscuring access to that rare survivor of an earlier era.

Dawoud Bey, Tourists, Abyssinian Baptist Church, from Harlem Redux, 2016. Pigmented inkjet print, 40 3/8 × 48 1/4 inches. Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, Stephen Daiter Gallery, and Rena Bransten Gallery. © Dawoud Bey.

The decision to forefront these photographs functions as a subtle reminder to exhibition-goers not to get lost in nostalgia for the past, in a too-easy identification with or celebration of the power and beauty of those pictured inside the galleries. In starting with these images, the curators ask us to consider the ways that racism and economics have robbed some of their own history, and to recognize the Black life that Bey records through this lens of survival. We are asked—not only by this work, but by all the work in the show—to see ourselves in others, but in doing so, to also confront our responsibility to them, to their pasts, and to their futures.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. She is co-curator of Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And at the Brooklyn Museum of Art; editor of Lorraine O’Grady’s book Writing in Space, 1973–2019 (Duke University Press, 2020); and a contributor to the New York Times. In 2020, she received a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant for short-form writing.