Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

At MoMA PS1, an “anti-retrospective” of the AIDS activist artist.

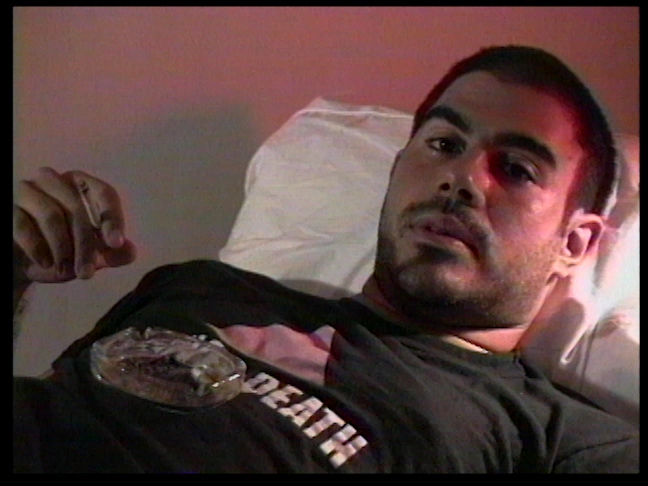

Gregg Bordowitz, Fast Trip, Long Drop, 1993, still. Courtesy the artist and Video Data Bank at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Gregg Bordowitz: I Wanna Be Well, MoMA PS1, 22-25 Jackson Avenue, Long Island City, New York, through October 11, 2021

• • •

In a slow panning shot close to the beginning of Gregg Bordowitz’s Fast Trip, Long Drop—the 1993 experimental autobiographical videotape that is perhaps his most famous work—the artist’s distorted reflection appears on the screen of a television set. The image doubles, disintegrates, and flares as the camera passes over the convex surface before stopping on his reclining figure; he lies on a bed in white briefs and a SILENCE = DEATH T-shirt, a thermometer in his mouth. Bordowitz, who learned he was HIV-positive five years earlier, at the age of twenty-three, says, speaking directly to the viewer, that he hopes he has the flu. It’s better than the other potential causes of his present high fever (among them tuberculosis, hepatitis, or a reaction to an experimental medication). Bored from staying home sick, he seems more detached than despondent in this proto-vlogger’s Brechtian address—though the vintage appropriated footage he cuts to offers a contradictory visual metaphor for his psychological state. In it, a high-diving daredevil, whose bodysuit is in flames, plunges into a pool lit on fire.

Another kind of blazing rupture greets visitors to Bordowitz’s retrospective—or anti-retrospective—at MoMA PS1. Titled I Wanna Be Well, after the Ramones song, the exhibition begins outside. A hazard tape–yellow banner, printed with crimson text, hangs above the museum’s main entrance, a blaring addition to the façade that reads “THE AIDS CRISIS IS STILL BEGINNING.”

Gregg Bordowitz: I Wanna Be Well, installation view. Pictured: Gregg Bordowitz, The AIDS Crisis Is Still Beginning, 2021. Courtesy MoMA PS1. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

The artwork, which is from 2021 (though it’s not the first time Bordowitz has employed the phrase), is a more emphatic and broadly allusive version of the healthcare-justice slogan “AIDS ISN’T OVER.” While both statements refer to the enduring inequalities of access to life-saving treatment, Bordowitz’s stands as a more pointed and poetic rebuke to the official AIDS narrative, to any single narrative with a fixed beginning and an end in sight, even as it recalls, for those old enough to remember, the ominous medical mystery reported by the CDC forty years ago last weekend. News of five young gay men in Los Angeles, diagnosed with a rare form of pneumonia, came to stand for the start of harrowing era of suffering and loss. (Theirs were not the first AIDS-related deaths in the US, but media coverage of their illness would set in motion the myth of a gay plague.) Bordowitz’s banner, with its vibrant, all-caps refusal of the elegiac, is a fitting prelude to the materials gathered in the galleries—work that powerfully and poignantly demonstrates the personal and collective representational strategies forged in the crucible of the AIDS movement in New York City.

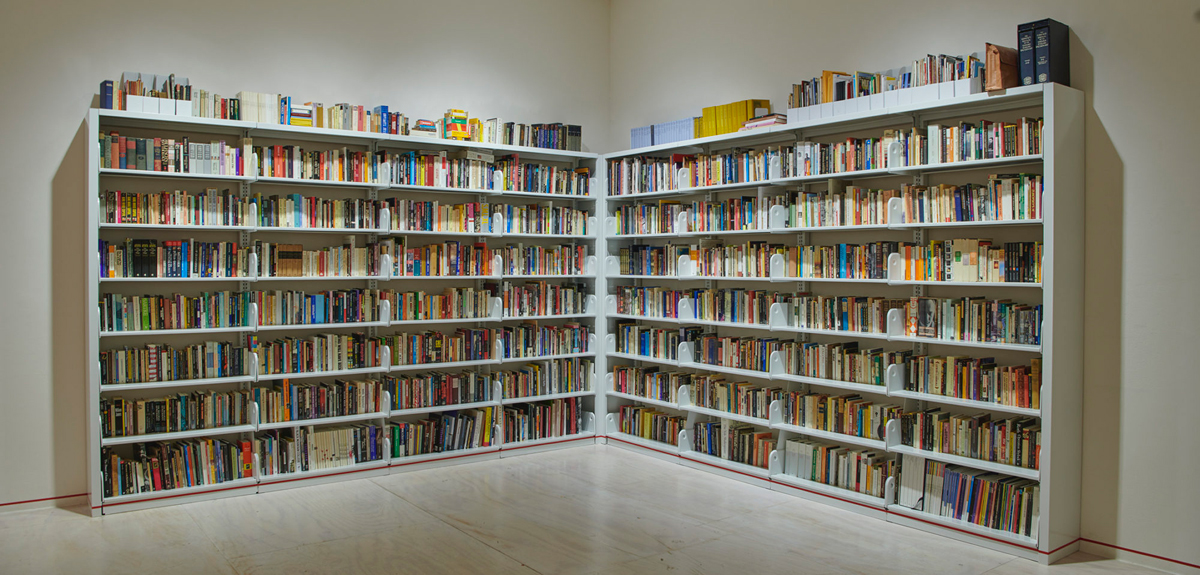

Gregg Bordowitz: I Wanna Be Well, installation view. Pictured: Gregg Bordowitz, Selections from Gregg Bordowitz’s library, 1983–2013. Courtesy MoMA PS1. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

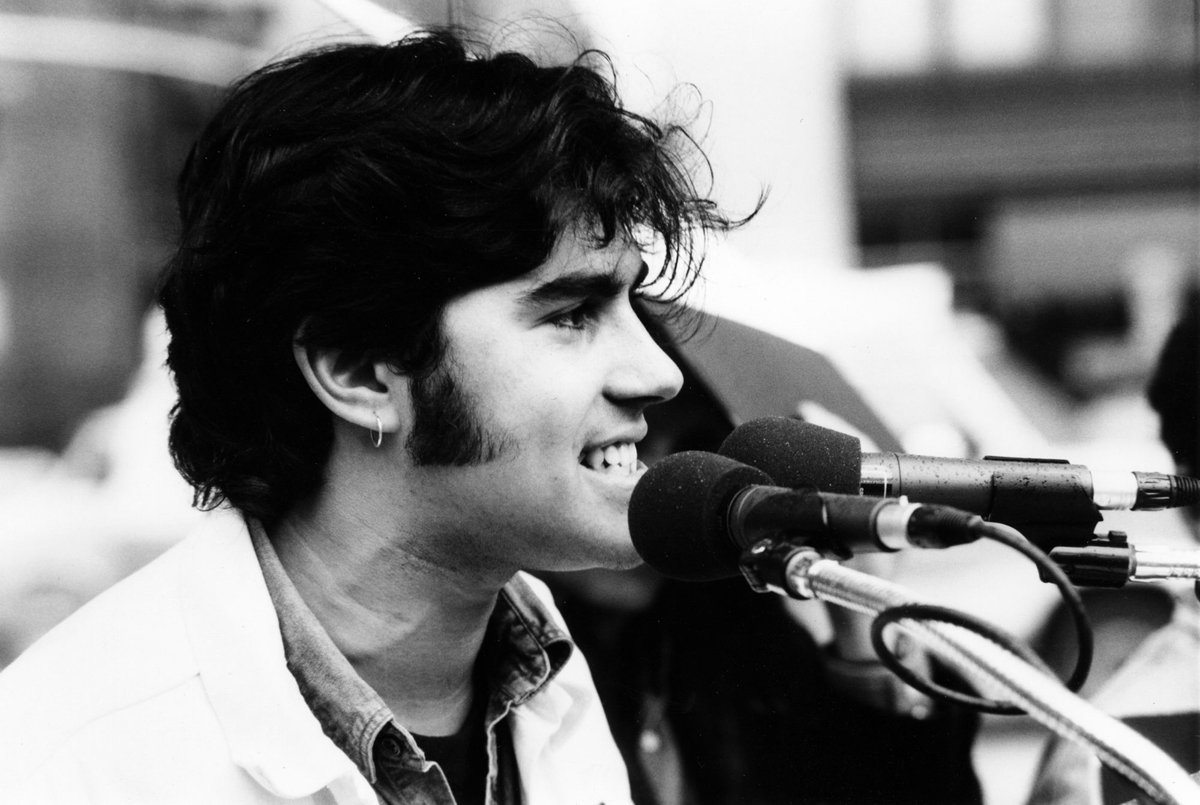

Described in the press release as a “record,” a term broad enough to be accurate, I Wanna Be Well lacks qualities I tend to expect from a survey—such as a roughly chronological presentation of a single artist’s evolution, or clear delineation between works of art and documentation or ephemera—which is fine, of course. (I was reminded of Julie Ault’s show-within-a-show in the 2014 Whitney Biennial, in which her sensitive grouping of works, also mostly related to the first decades of the AIDS crisis in New York, eroded stale historicizations of that time.) Here, Bordowitz is something of an organizing principle, a prominent through line in an exhibition that includes things as varied as a sweeping expanse of his personal library, a small abstract pastel-and-graphite work on paper by painter Jack Whitten from Bordowitz’s own collection, and a group of photos taken at AIDS demonstrations in 1988. There’s a shot of an irate fresh-faced cadre of protestors in Cher T-shirts, and an image of activists tracing their bodies in chalk in the street by Tom McKitterick; also a close-up by Lee Snider of Bordowitz addressing a crowd.

Lee Snider, Gregg Bordowitz addressing AIDS Activists during protest in NYC, 1988. Gelatin silver print, 8 × 10 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Bordowitz became a video activist in the eighties. He was a documenter of and participant in ACT UP New York’s direct actions, a member of the video collectives DIVA TV and Testing the Limits, and a producer of cable-access broadcast pieces for Gay Men’s Health Crisis. He was also a member of a group of queer artists who, as he wrote in his 1993 essay “The AIDS Crisis Is Ridiculous,” “took ideas current in the art world—appropriation, situationist strategies, institutional critique—and applied them to the struggle to wrest control of the public discussion of AIDS from right-wing fanatics who proposed homophobic and racist policies.”

Gregg Bordowitz, some aspect of a shared lifestyle, 1986, still. Video (color, sound); 22 minutes, 23 seconds. Courtesy the artist and Video Data Bank at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The early tape some aspect of a shared lifestyle (1986) is exemplary of an exhilarating strain of media critique. His own protest footage bleeds into found clips and satirical performances (Bordowitz in a lab coat challenging the biases of epidemiology, or in a blazer, playing a fear-mongering news anchor). In contrast, a series of vignettes from 1992–95, with the straightforward title Portraits of People with HIV, adopts an intimate and anti-sensationalist tone to counter prevailing mainstream depictions of people like his subjects. The aforementioned Fast Trip, Long Drop breaks from these activist modes. While, in it, he puts a person with HIV on television, literally—by capturing his own reflection on the set, in a sardonic nod to a principle of AIDS-movement media, the goal of depicting a coalition of self-determined protagonists—the piece is steeped in ambivalence and existential fear. It features him as an unreliable, role-playing narrator, foregrounding a kind of fractured truth-telling unconstrained by the mandate to be empowering or hopeful. “Political art must adopt the imperatives of an activist movement as its starting point, not its end,” the artist reflected later.

Gregg Bordowitz: I Wanna Be Well, installation view. Pictured: Gregg Bordowitz, Fast Trip, Long Drop, 1993. Courtesy MoMA PS1. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

Bordowitz’s historic tapes—longish single-channel pieces made for television broadcast or film programs—do not, alas, work well as installations, projected in large rooms with just a few seats (or on monitors, looping). So, though his moving-image work forms the core of the show, viewers will find it nearly impossible to see most of it in a single visit. Fortunately, the considered manner in which this material is contextualized or upset by endeavors in other media makes for a lasting takeaway. The understated, brusquely executed drawing series self-portraits in mirror (1996) tracks a period of self-scrutiny occasioned by the antiretroviral therapies that dramatically changed the prognosis for those living with HIV; a new mixed-media sculpture updates Vienna’s famous “Plague Column,” erected after the plague of 1679. Bordowitz brings the commemorative statue into the era of the AIDS and coronavirus pandemics, with his expressively rendered, un-celestial figures, including a protestor in a surgical mask with a blank picket sign. Savvy exhibition-design elements are used to quietly dramatic effect.

Gregg Bordowitz: I Wanna Be Well, installation view. Pictured: Gregg Bordowitz Pestsäule (after Erwin Thorn), 2021. Courtesy MoMA PS1. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

Installed throughout the show are the twenty-four poems of the artist’s 2014 cycle Debris Fields, emblazoned on the walls in vinyl lettering. The lines are formed by an unrelenting procession of nouns, banally or beautifully associative, capturing the textured monotony of consciousness (“SPELLCHECK REFLEX NERVE BUNDLE HAMMER”) or the language trail of a mind surveying—as the work’s bleak title suggests—wreckage of various kinds (“VEXATION EXHAUSTION PLANNING TERROR”). A red stripe racing along the bottom margin of the exhibition’s walls complements these airy columns of poetry, evoking an empty timeline, a boundary, a correction, as well as an endless bleeding incision. It serves to unite, or corral together, the exhibition’s unruly, refreshingly heterogenous contents; it encircles the output of a creative life and a radical community rather than that of a mere art career.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.