Erika Balsom

Erika Balsom

In Lizzie Borden’s 1986 film: sex and labor.

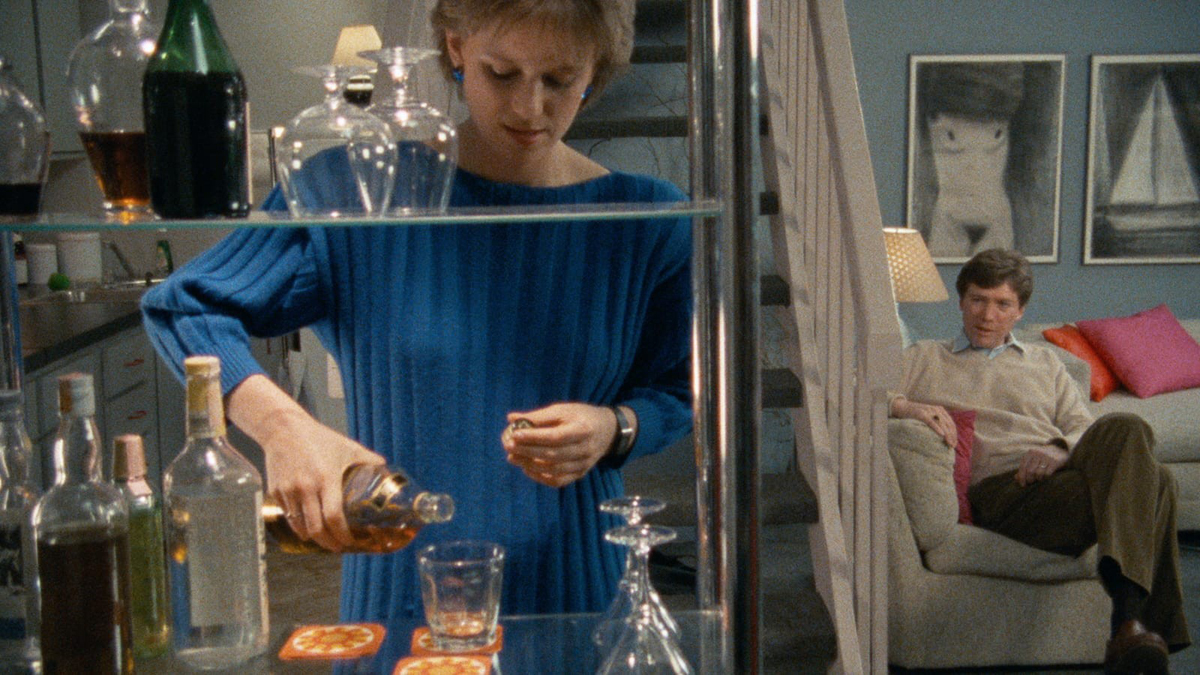

Louise Smith as Molly in Working Girls. Courtesy Janus Films.

Working Girls, directed by Lizzie Borden, opens June 18, 2021, at the IFC Center, 323 Sixth Avenue, New York City; available on DVD and Blu-Ray from the Criterion Collection July 13, 2021

• • •

Made with sangfroid during the heat of the 1980s sex wars, Lizzie Borden’s Working Girls (1986) is a film preoccupied with the know-how of women on the job. Molly (Louise Smith), a Yale-educated photographer, tricks part-time to pay the bills. Unexpectedly, she ends up working a double shift under pressure from Lucy (Ellen McElduff), the hoity-toity madam who insufferably tries to coat the pill of exploitation with the cloying sweetness of feigned friendship. In a Manhattan apartment, decorated in a strange but telling blend of the domestic and the impersonal, a picaresque of sex work unfolds. Molly’s time is measured out in the repeated alternation of client meetings and the spells of sociality that fill the gaps between them, when she and her coworkers sit downstairs in the living room, chatting and bickering, juggling practicalities and colluding to stiff the boss lady. The drag of this day blots out the rest of life. Is it all worth it? Costs and benefits make up the calculus of survival, and Working Girls is all about keeping track of the ever-changing tally, without passing judgment.

Amanda Goodwin as Dawn, Ellen McElduff as Lucy, Marusia Zach as Gina, and Louise Smith as Molly in Working Girls. Courtesy Janus Films.

Near the beginning of their 2018 book Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights, Juno Mac and Molly Smith make an important observation, one that throws into relief the critical move made by this smart, enjoyable film: many who have not sold sex themselves tend to think about the activity principally in symbolic terms, such that its weighty cultural meanings overwhelm any consideration of the material realities of sex work. “Sex workers have long noted with ambivalence the interplay between prostitution as a site of metaphor and as an actual workplace,” they write, pointing to how feminists of different stripes have enlisted a generic notion of “The Prostitute” to fight ideological battles at a distance from sex workers’ own priorities. She might stand united with the housewife, as the hyperbolic emblem of the exploitation of all women under patriarchy; she might be deemed abject, little more than “vaginal slime,” as Andrea Dworkin memorably put it; or she might be held high as a sex-positive avatar of empowerment. No matter how she is cast, these abstractions eclipse a concern with the particularities of sex work as work. Working Girls—winner of a Special Jury Prize at the 1987 Sundance Film Festival and now circulating in a new restoration—redresses this balance with humor and care, delving into the unspectacular grind of selling sex while never entirely giving up a foothold in metaphor.

Louise Smith as Molly in Working Girls. Courtesy Janus Films.

The film was a leap into the mainstream for Borden, the director of Regrouping (1976) and Born in Flames (1983), feminist classics that also explore the social dynamics of female collectivity, albeit in more experimental idioms. Working Girls has a curious feel to it, somehow gelid and bustling at the same time, mixing naturalistic detail with a fondness for stereotype. It catalogs the gestures and routines of a single day’s labor with anthropological perspicacity, taking inventory of an array of events and personalities too heterogeneous to congeal into any blanket moral message. The pleasure of the film derives less from the thrill of spying on explicit encounters (although these are presented) and more from the ways it makes explicit all that it takes to get the job done. The contents of the supply closet, the answering of the telephone, and the circulation of cash receive ample attention, embedding the sale of sex within a repertoire of administrative tasks that possess none of the salaciousness of genital contact. At the same time, Borden is wonderfully allergic to a euphemistic view of embodied existence, picturing a bloody diaphragm washed out in the sink and ketchup squeezed onto a hamburger with the same frank regard. When she films sex, it is as no special peak (or pique) of interest, but as a desublimated act that is frequently milked for comic value. The men’s orgasms? Beside the point.

Louise Smith as Molly in Working Girls. Courtesy Janus Films.

All this close observation of professional protocol occurs across an onstage/backstage divide that gives the film shape and rhythm. A different movie would carve out an easy split along architectural lines, with the “backstage” interactions tidily revealing the face behind the mask, supplying a reassuring dose of authenticity. Working Girls toys with this idea only to reject it, making an argument about the social field it depicts in the process. Here, the real and the fake not only coexist; they can be hard to tell apart. There are moments of seeming genuineness upstairs with clients, while codes and scripts saturate the backstage moments downstairs. In the bedroom and outside it, these women squeeze to fit the roles they must play, in ways that are at times worth it and at others not.

Working Girls. Courtesy Janus Films.

Borden shows the strain of type, but she also works with it, populating her film with stock characters. There is Molly, the college girl; Dawn (Amanda Goodwin), the self-proclaimed whore; Mary (Helen Nicholas), the reluctant first-timer. The men, even more so, are sketched in broad outlines. It would be easy to see this as a concession to mainstream convention, and perhaps it is. Yet it is worth recalling that when Claire Johnston laid out a vision of “women’s cinema as counter-cinema” in 1973, what she had in mind was not avant-gardist experimentation but an infiltration of the entertainment film—one that might appropriate stereotype as a weapon. By foregrounding the constructedness of representation, stereotype marks out a distance from reality, breaking with the impression of naturalness that many films strive for. Working Girls revives this idea, orchestrating a fascinating collision between schematic artificiality and ethnographic proceduralism. Each mode undercuts the claims of the other, allowing the film to push back against the abstraction of “The Prostitute” while tempering any claim to sociological truth.

Like so many people, the women of Working Girls have conflicted feelings about what they do for money. If there is an antagonist here, it is not the clients; it is the madam, who reaps her reward off her employees’ backs. By displacing the primary site of exploitation from the patriarchy to the female proprietor, Working Girls punctures the myth of sisterhood and reconciles the opposition that Mac and Smith underline, between the material reality of sex work and its treatment as metaphor. In this film, sex work is work and an allegory for life in the service industry, whatever the service may be. As Borden put it in an interview, “Actually, the greatest compliment I ever got for Working Girls was when some guy said to me afterwards, ‘I had a boss just like that.’ ”

Erika Balsom is a Reader in Film Studies at King’s College London. Her book on James Benning’s TEN SKIES (2004) is now available from Fireflies Press as part of its Decadent Editions series.