FT

FT

Inside and outside: a history of the early years of ACT UP New York.

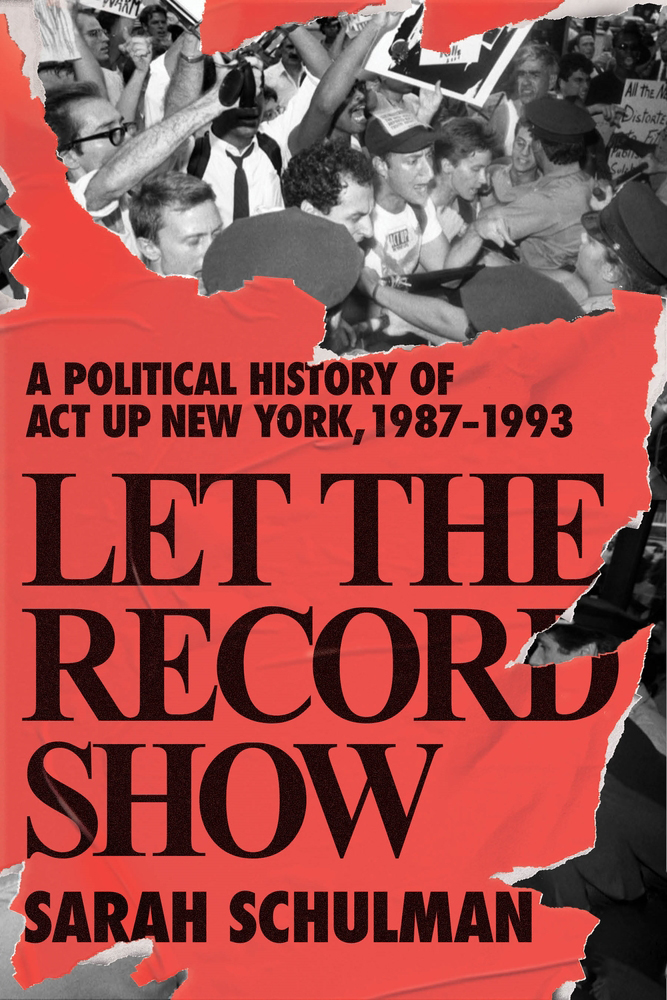

Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993, by Sarah Schulman, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 702 pages, $40

• • •

Sarah Schulman’s new book, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993, is the remarkable, timely capstone to her decades-long labor of documenting the improbable miracle that was and is ACT UP. A legendary name in the story of HIV/AIDS activism, the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power turns thirty-five next year and is still going strong, but the full scope of its achievements remains widely underappreciated. Schulman and fellow ACT UP veteran Jim Hubbard spent seventeen years collecting 188 long-form interviews with current and former ACT UP members. The interviews have previously been condensed into the documentary United in Anger (2012), and now serve as the book’s raw material.

Between 1987, when the group came together in the wake of an incendiary speech by Larry Kramer, and 1993, when Schulman’s record ends, ACT UP changed the world. It transformed the response to HIV/AIDS in every branch of the United States government, changing the FDA’s drug-approval process, pushing the CDC to revise their definition of the disease, and winning crucial judicial victories. It produced a haunting and indelible iconography and a significant body of creative work. It compiled and disseminated life-saving information in clear and accessible form in a time before email and social media. And it rewrote the playbook on direct action and civil disobedience in the US. Staging some of the most memorable demonstrations in American history, ACT UP revived tactics learned in the feminist, anti-war, and civil rights movements but blended them with an ingenious gaming of the American media establishment and tenacious direct pressure on key government officials, most prominently America’s then de facto AIDS czar, one Dr. Anthony Fauci.

The anger and growing desperation of the epidemic forged an improbable coalition of strangers. Many still had boots on from earlier political struggles: the expertise of these veterans was crucial to early successes, and a link to earlier traditions of direct action. Joining those veterans were novices on the stage of political activity, white gay men with Ivy League degrees and connections on Wall Street, at City Hall, and at the New York Times, men with access to Connecticut and Hollywood money. Among the marvels of ACT UP in its early years was its success at fundraising. It’s easy to forget in light of his greater legacy that Kramer was nominated for an Oscar before he was an AIDS activist. This access made possible what Schulman calls the “Inside/Outside strategy”: “one arm of the movement in direct, personal relationship to government or corporate officials . . . having intimate interactions, and creating identification. . . . At the same time, a different sector of the organization provided backup and pressure through street actions . . . playing the role of Outside. . . . In 1987, most people in power were white males . . . and this determined which AIDS activists had the potential to be Inside and which ones would be relegated to Outside.”

In Schulman’s telling, this approach was both the key to ACT UP’s success and the root of its disintegration. The access that made the Inside half of the strategy possible generated a visible divide once treatments for HIV/AIDS became available; by 1992, it was clear that some “members were overwhelmingly healthy in comparison to other groups of people with AIDS in ACT UP.” The Inside/Outside strategy is how white gay men, many of them young and attractive in their desperate rage, came to be the historical face of ACT UP, and how ACT UP came to be remembered primarily for agitating on treatment and drug access, as opposed to other crucial issues, like needle exchange and access to health insurance for women with HIV/AIDS.

Without polemic or resentment, the book is explicit in its corrective intent. It rejects the common attribution of leadership to Kramer and the crudely gendered myth that lesbians participated in the AIDS activism movement as “caretakers” of the gay men who were doing the fighting. Schulman counters with crucial examples of overlap between AIDS issues and reproductive-rights issues, giving richly deserved credit to the strategists behind ACT UP’s interventions on these topics, many of them lesbians with extensive political experience. There were and are women with AIDS, and many people who weren’t gay men played crucial roles in the movement.

Neither traditional scholarly historiography nor a proper oral history—much of the story arrives by way of a semi-omniscient first-person narrator—the subtitular “political history” is apt: Let the Record Show is a guide to the politics of the archive. Having done the immense labor of collecting these testimonies, Schulman wants to make sure you hear them in their full and sometimes contradictory complexity, and to understand why some of the names are more familiar to you than others. Offered an archive of nearly two hundred in-depth interviews, many viewers no doubt gravitate to the names they already know and unconsciously repeat the biases the archive means to correct. (The complete videos are publicly archived at the New York and San Francisco Public Libraries, and at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; clips and full transcripts are available at actuporalhistory.org).

The archive is deep, and the book’s tasks are many. The fact that Let the Record Show only scratches the surface is not a critique but a sad acknowledgment of historiography’s realities. It took countless hands and feet to realize the grand vision behind ACT UP’s activity, hundreds and later thousands of committed members putting their bodies and time and careers on the line. Even the Outside had an outside: the photocopying and flyering and travel booking and phone banking and all the endless labor that went into doing what the group did, which frequently included caring for members as their health declined and arranging their funerals. In the early ’90s, ACT UP members in their devastated fury made the funerals themselves into political spectacle. Death is everywhere in the book, but in the early parts the action develops swiftly and mortality wears a grim, stoic face. In the final chapters, death and pain roar out with brutal and lyrical precision.

The opening note begins: “Let the Record Show is a look at the individuals who created ACT UP New York.” But what emerges as the framing narrative is Schulman’s own memorializing, her effort to make sense of what she experienced. The book’s arc reproduces with masterly pacing the experience of those tumultuous early years: the disorienting introductory rush dropping us into the middle of ACT UP’s most famous actions; the shift in attention from an initial focus on the biggest names to the everyday members; the alphabet soup of medications that starts with nothing but AZT and eventually spirals into a flood of abbreviations and treatments; the incandescent rage giving way to exhaustion and frustration and pent-up grief; and the funerals, the funerals that started in the 1980s and still haven’t stopped.

AIDS is not over; and ACT UP is not over; and the death and grief and remembering aren’t over, either. This isn’t the only book on ACT UP, or the definitive book on ACT UP. It’s Sarah Schulman’s book on ACT UP, a powerful document of a harrowing and enduring tragedy, and of the relentless determination to act up, fight back, and fight AIDS.

FT isn’t a real person, but that doesn’t seem to stop them from having a lot of opinions. You can find their work online.