Mark Sinker

Mark Sinker

Wandering the Wonderland: an ambitious exhibition dives into a character and her influence.

John Tenniel, Alice at the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party, illustration for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, 1865. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser, Victoria and Albert Museum, Cromwell Road, London, through December 31, 2021

• • •

On a hot July 4 in 1862, in the heart of the widest-flung empire in history, an oddball virginal bachelor took three daughters of one of this empire’s great classical scholars on a boating picnic just outside Oxford. The daughters were Lorina (thirteen), Alice (ten), and Edith Liddell (eight); the oddball (thirty) was Charles Dodgson, lecturer in mathematics, soon known to the world as Lewis Carroll. And Alice? Alice is also known to all the world, and a current exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum sets out the evidence of this reach, gathering what went into Carroll’s two books (1865’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1871’s Through the Looking Glass), and much that has filtered back out, into film and fashion, theater, politics, pop, and briefly even some vanguard science (a large ion-collider experiment that took the playful acronym ALICE).

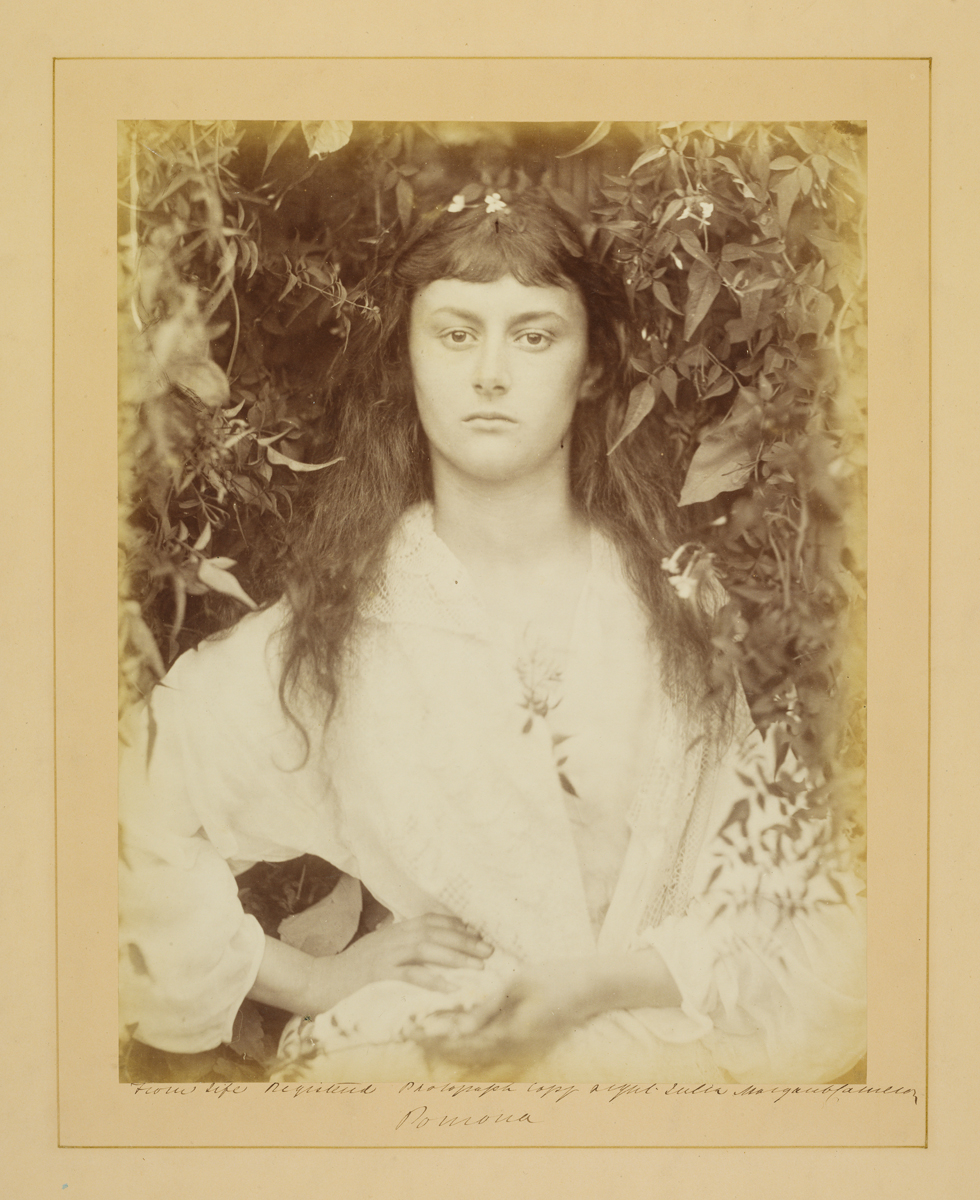

Julia Margaret Cameron, Pomona (Photograph of the “real” Alice Liddell), 1872. Albumen print. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

It’s a lot—perhaps too much. As an institution predating the Liddell picnic by a decade, and housed in many-roomed nineteenth-century splendor, the V&A has enormous resources and gravitas to draw on, its extensive collections of fashion and design taking pride of place in shows like this. As an exhibition, Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser has scope and ambition—though perhaps not enough connective tissue, or will to make the viewer stop and delve.

Still, the opening section, “Creating Alice,” is promising in its profusion, hinting at the Alice-sounding premodern Wunderkammer (or cabinet of curiosities). Here in old-style vitrines are sepia photos of Carroll and his milieu, this shy logician cushioned within the upper bohemian-Victorian cultural layer, with Tennyson, Ruskin, the Pre-Raphaelites, and the Arts and Crafts movement all close at hand. But if Wonderland began life as a rarefied private gift, adult to child, its transformation into a best-selling book came via illustrator John Tenniel of the smart-set satirical periodical Punch.

Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser, installation view. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Carroll’s own rough illustrations, handwritten notes, and diagrams are on view in this section, alongside Tenniel’s preparatory sketches and other professional commissions. Out of the friction of the two men’s sensibilities would press parodies, poems, and tales, involving tears, rage, and madness. Alongside dance, games, education, mirrors, fallings and vanishings, the two volumes portrayed memory and its failure, the conundrums of identity, nested dreams, bizarre cuisine, and perverse domesticity. Familiar clichés writhe into self-mocking life; via stubborn adherence to literal meaning, conversations become tussles of insult. The books constantly circle the childhood fascinations of eating and mortality. A death sentence hangs over the trial of the stolen tarts. For all its happenstance companionships, the chess-game world is a war zone studded with one-on-one battles, climaxing in a queenly feast where the food itself explodes into revolt.

From the second section, “Filming Alice,” onward, we see well-loved characters, scenes, images, and ideas as they transfer beyond the books. The exhibition is roomier now, the dozen or so films displayed as loops on monitors, and the rabbit holes feel more siloed: where the Wunderkammer style perhaps encourages an unstructured speculation, the will to explore—whether we linger or hurry on—begins to brigade us a little away from the jarringly disparate lines of philosophy we might discover with a deeper compare-and-contrast. For example, there’s a huge unexamined gulf in sensibility between Jorge Feliu’s Alicia en la España de las maravillas (Alice in Spanish Wonderland, 1978) and the Czech animator Jan Švankmajer’s Něco z Alenky (Something from Alice, 1988). Both are political satire, but while the kids attending this show will likely identify with Švankmajer’s wide-eyed, fearful protagonist, surrounded by alarming taxidermy animals, all teeth and nails and leaking sawdust, Feliu’s more unpleasant content will not be seen in the clips used—the assaults on several teen Alices by glib Franco-ite businessmen.

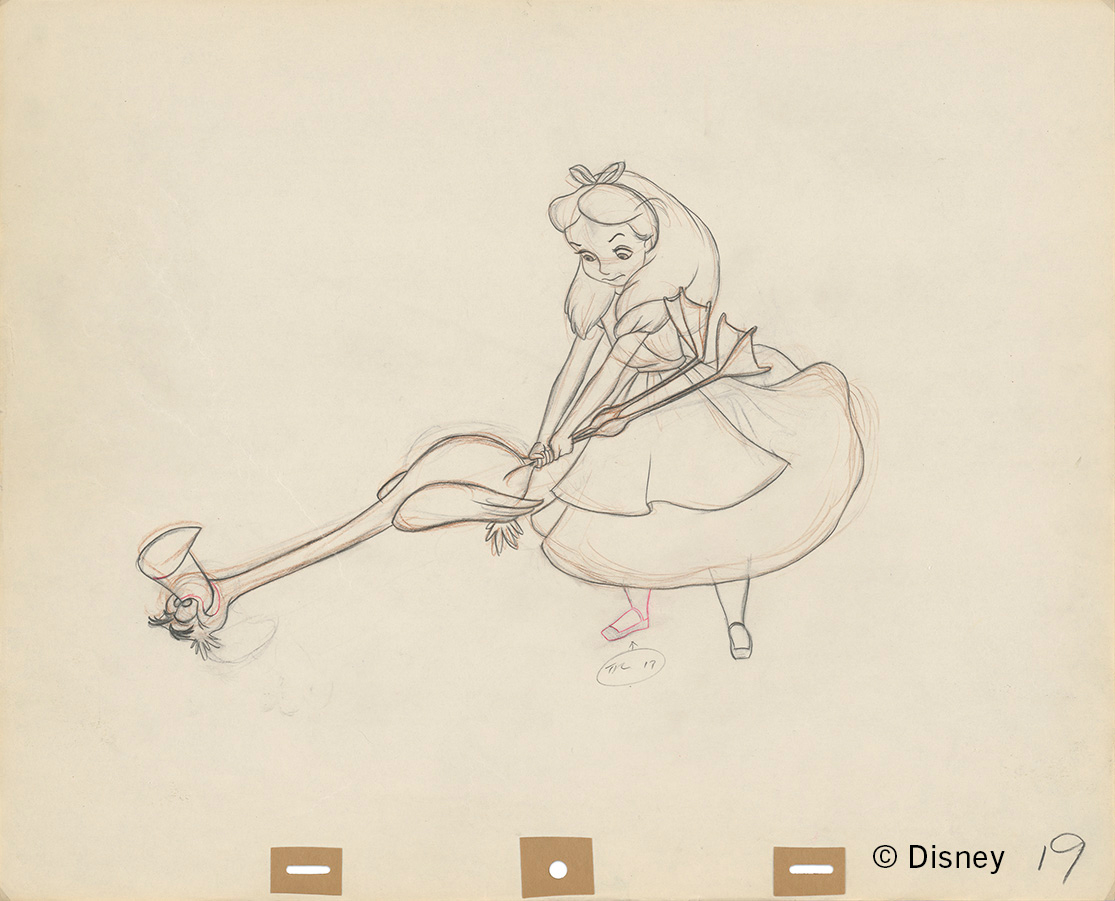

Mary Blair, concept art for Walt Disney’s animation of Alice in Wonderland, 1951. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum. © Disney.

Remakes from the movie mainstream take us from the very first Alice in Wonderland on film (a ten-minute silent movie directed by Cecil Hepworth and Percy Stowe in 1903) to the full-length Disney cartoon of 1951. Often seen as favoring Tenniel’s iconography over Carroll’s subversive depths, these too cannot avoid engaging with the absurd rigmaroles of growing up, of royalty, rules and the law—if only because so much of their cinematic technology is reserved for shifts and reversals in size. Walt’s Alice was in plan for some twenty years, and we see character and scene designs, as well as fragments of un-filmed script, that reveal its in-studio progress as an abandoned succession of high-concept projects deemed too complex or scary, some by intriguing staffer artists like David Hall and Mary Blair, some from such avant-celebrity guests as Aldous Huxley and even Salvador Dalí.

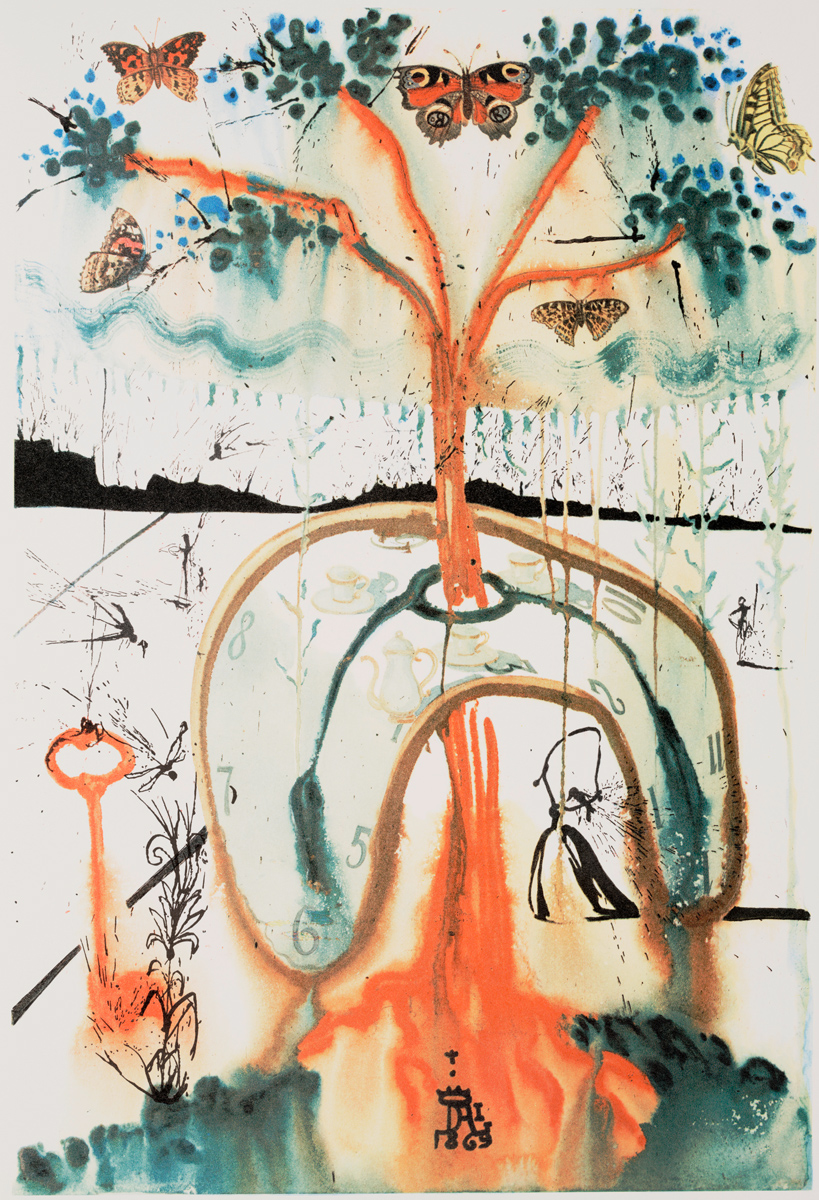

Salvador Dalí, A Mad Tea Party, 1969. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum. © Salvador Dali, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS 2019.

The next V&A section is “Reimagining Alice,” featuring two contrasting avant-gardes, the Surrealists and the Psychedelic Underground. Leaders of the former explicitly cited Alice as their precursor in dream-mining and the bricolage of bric-a-brac to reframe civilization as a mere veneer over dark primordial urges: a single page from Max Ernst’s collage novel Une semaine de bonté (A Week of Kindness, 1934) uncovers the weird brooding threat in Tenniel’s image of Alice in the railway carriage. Psychedelia rejected such pessimism: sex was now the unspoiled desire-reality of the young, Alice as the first hippie would conquer war and cruelty, all of Carroll was an amazing druggy head trip, and Disney too. (These are the kinds of connections and contrasts that a gallery show does well.)

A wall of mainstream political cartoons blocks our way—but its borrowings are tiresome and normative, and we can fly past them straight into the closing sections, “Staging Alice” and “Being Alice,” for what theater, fashion, and pop find in Alice . . . and won’t find.

Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser, installation view. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Because it turns out our heroine is often a rather passive sidekick. To ignite the drama in these narratives, an Alice must act on grown-up appetites and instincts, her age now as uneasily mutable as her size once was in Wonderland. The Alice cosplay of such featured pop stars as Lady Gaga or Janelle Monáe begins with an outspoken sexuality. If what they wear is the armor of empowered twenty-first-century feminist identity, it’s also the mad-hatter bread-and-butter of present-day stage and fashion designers and milliners. Carroll was infatuated with preteen innocence, and it’s unsettling to imagine him processing the twenty-first century’s very different sexual shibboleths—but nevertheless, the capacious wardrobes at the V&A are today hung deep with Alice-related items, as we now see, from the hands of Vivienne Westwood, Viktor & Rolf, the street fashions of the Japanese Lolita cult.

Viktor & Rolf, haute couture autumn/winter 2016—Vagabonds. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum. Photo: Team Peter Stigter.

Of course, this show (like this review) can barely scratch the surface, many puzzles remaining untouched. With the exhibition’s plenitude comes a hint of panic—and one great omission or failure of nerve. Language is never really tackled as a theme. Think of the poem “Jabberwocky,” in which a fabulous monster surges through dense bestiaries of made-up words, to be slain by a child warrior: “The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!” Yes, explanatory text and detail are often off-putting, but in that case, why not use Carroll’s approach as a guide? His boldness is video-game vivid here because he recognizes and enjoys the power behind the unfamiliarity—and look how he’s trusting his seven-year-old heroine’s curiosity! Think of we visitors as frabjous child warriors, wide open to the perils of play-conflict and to the uncanny and demanding strangeness of words. Sometimes they bite, but that’s part of the adventure we’re looking for.

Mark Sinker has written about music, film, and the arts since the 1980s, at outlets including Sight and Sound, Crafts magazine, the Face, and the Village Voice. In the early 1990s he was editor of the Wire, and in 2019 published an anthology of essays and conversations about UK music-writing, A Hidden Landscape Once a Week: The Unruly Curiosity of the UK Music Press in the 1960s-80s, in the words of those who were there.