Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

From keychain Jesus to plaster Mao: a veteran artist explores the psychology of things.

Liliana Porter: Other Situations, installation view. Image courtesy El Museo del Barrio. Photo: Martin Seck.

Liliana Porter: Other Situations, El Museo del Barrio, 1230 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through January 27, 2019

• • •

In his 1853 essay “The Philosophy of Toys,” the French poet Charles Baudelaire noted children’s propensity to see animation in those inanimate objects. Watching youngsters’ pleasure in talking to their playthings and their ability to overlook the shift in scale required to imagine a tiny figurine as an actual breathing soldier, he said, we see children’s “great capacity for abstraction and their high imaginative power.” Children, he argued, have an “infantile mania”—their first “metaphysical tendency”—to see the souls of their dolls and games; the reason so many kids tear apart their toys as soon as they receive them is that they’re searching out this life force. (Imagine: that graveyard of headless Barbies in my toy box was actually the result of me seeking my god.)

The Argentina-born, Mexico-educated, and New York–based artist Liliana Porter has moved, in her long career, from work in printmaking (she was a cofounder, with Luis Camnitzer and José Guillermo Castillo, of the New York Graphic Workshop in 1964) to, in the last decade or so, tapping into such “infantile mania” as Baudelaire describes. Though including works dating back to 1969, the exhibition Other Situations, organized by Humberto Moro for the SCAD Museum of Art and now on view at El Museo del Barrio, focuses largely on this latter tendency in her oeuvre. Over the years she has scoured antique stores, junk shops, flea markets, airport concessions, and so on, gathering the raw materials for her explorations of the inner lives of toys. In photographs, drawings, small installations, canvases, film—and most recently, theater—she uses these resonant objects to reveal the psychology of things, our investment in commodities, and the fine line that separates incessant labor from comical, if Sisyphean, play.

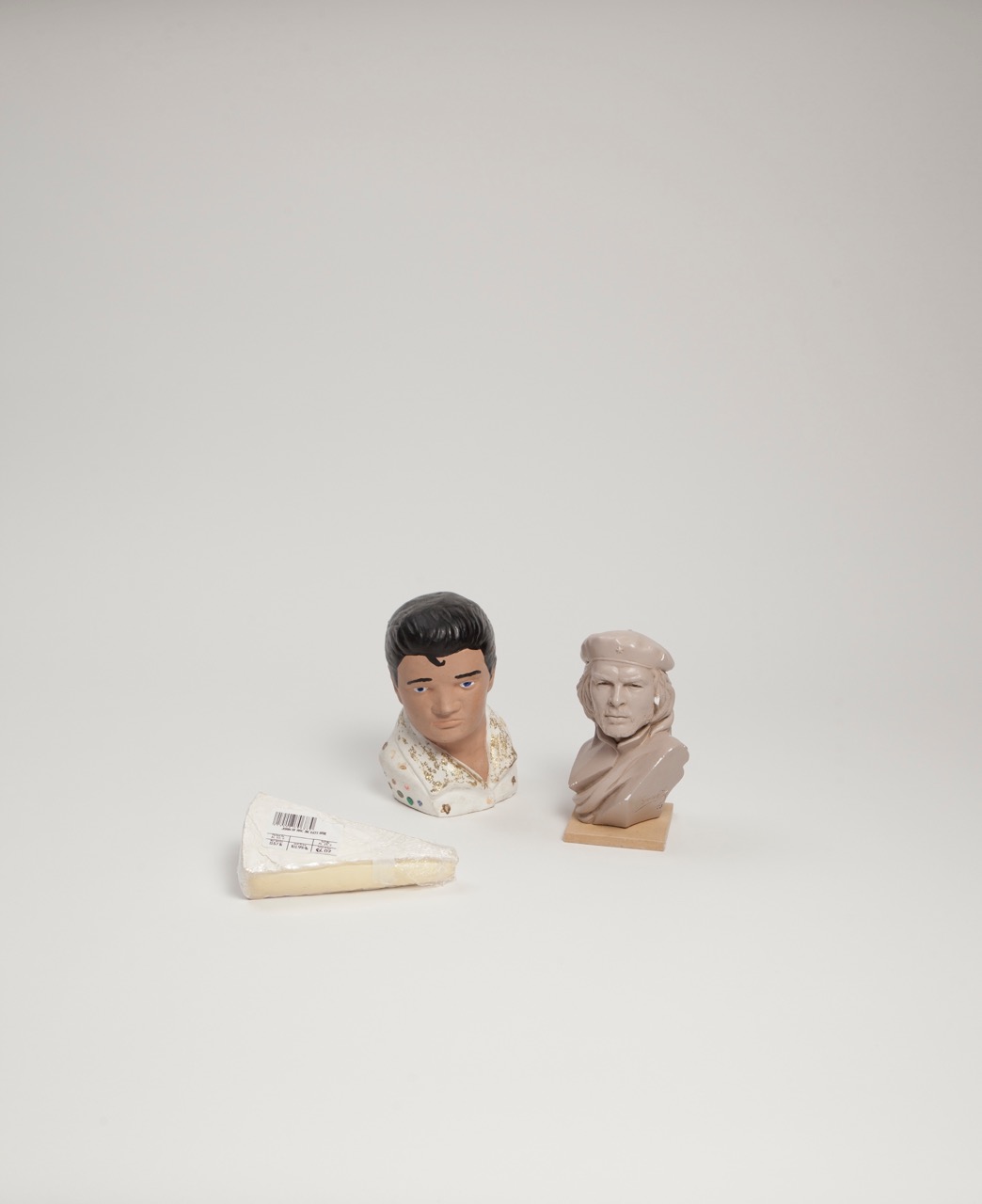

Liliana Porter, Joan of Arc, Elvis, Che, 2011. Digital Duraflex. Image courtesy the artist.

The first work on display is Joan of Arc, Elvis, Che (2011), in which stand-ins for the three icons are photographed against an unmodulated, white background. We are given no context, no sense of scale, nothing to indicate why the saint, the star, and the revolutionary are brought together. Elvis, in the middle, is a souvenir effigy, his doughy face and sparkly jumpsuited shoulders painted with a plodding hand; Che is a plaster bust mounted on a small piece of wood, all piercing gaze and chiseled cheekbones and fashionably voluminous scarf; and Joan of Arc is . . . a plastic-wrapped hunk of Brie. Yes, the cheese—this particular brand name has delusions of epic martyrdom, apparently.

Liliana Porter: Other Situations, installation view. Image courtesy El Museo del Barrio. Photo: Martin Seck.

The image is a light-handed demonstration of the ways in which our objects of veneration become—quite literally—objects of consumption and vice versa, and the sometimes laughable degree of leveling that occurs as a result. Porter delights in bringing together the most unlikely bedfellows in photographs of her collected treasures. The Intruder (2011), for example, assembles a plaster Chairman Mao, a Japanese porcelain doll, a small plastic Pinocchio, a sow and her piglet in the form of a clock, a Jesus keychain, a fuzzy duckling, a saucy poodle, a creamer illustrated with Lassie and a sugar bowl with George Washington, and, eerily, a small toy car—a replica of the black convertible the Kennedys were riding in, with teeny-weeny figures representing JFK and Jackie, on the day of the president’s assassination. All these characters look happy to be together, even though, by virtue of differences in their style, functionality, temporality, politics, and even species, they would never share the same space except in Porter’s whimsical collection. The effect reminds one of Borges’s description of a (fictional) Chinese encyclopedia—The Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge—which offered an unconventional, if hardly disputable, alternate taxonomy of animal classification: those that belonged to the emperor, embalmed ones, those that are trained, suckling pigs, fabulous ones, stray dogs, etc.

A series of eight photos, printed on metal, form the 2005 piece For Instance/Por ejemplo, in which a mass of found figurines appears as a huddled crowd from different vantages, ranging from mid-distance to close up. Here, Porter’s keen curatorial eye becomes apparent: it’s clear that she chose her toys for their facial expressions, their ability to communicate something like fear or unease or discomfort or melancholy. No matter what the vast disjuncture of scale on display—babies are huge and miniscule by turn—it is the mix of types that is most jarring. Where else would you find grouped a sad SS officer rubbing shoulders with a slightly maniacal Noddy (a beloved character from Enid Blyton’s children’s book series, and a toy himself), a pie-eyed Mickey Mouse, and some slightly apprehensive, banner-waving Chinese revolutionaries? The only thing that connects them is their wary eyes and a high-keyed palette typical of the visual world of children—and yet the pictures have all the psychological intensity of the best crowd photography.

Liliana Porter: Other Situations, installation view. Image courtesy El Museo del Barrio. Photo: Martin Seck.

In the handful of galleries that make up the elegantly hung and expansive-seeming show, we are confronted with several small installations centered on tiny people-substitutes undertaking impossibly huge tasks. A small man in a white smock is mounted on a wooden block on one wall; from his paintbrush seems to emanate a French blue swath of paint that grows bigger and bigger, enveloping a good part of two walls of the room (Man Painting, 2018). Nearby, another figure begins the herculean job of painting a leg of a full-sized chair, many, many times his height, that same shade of blue (Untitled [Man Painting Chair III], 2015). In Man with Pickaxe (2017), a miniscule man chips away at the long wooden plinth on which he stands (it must be at least eight feet long to his inch or so height), presumably intent on destroying his own foundation. Forced Labor (Sweeping Woman) (2004–18) has a woman in a green skirt and straw hat cleaning up a spill of blue sand that stretches almost endlessly before her. Another woman, all in pink, sits on a tiny bench, knitting; the result of her efforts is the delicate mound of pink fabric that covers most of the large white box on which she is installed (The Weaver, 2017). One man tries to tune a smashed toy piano many times his size (The Task [Black Piano], 2016), while another tries to wind a crushed clock (To Fix it 3:30, 2016).

Liliana Porter, To Fix it 3:30, 2016. Figurine on clock and shelf. Image courtesy the artist.

In 1853 Baudelaire decried the play of little girls—it was not imaginative, he insisted, and was more invested with training them for their future roles in the household (though why he thought boys playing with soldiers were any freer in their activities is anyone’s guess). Porter’s scenarios remind us that work and play have always been more closely aligned than their false opposition in language might suggest. As we descend deeper into what some call “ludic capitalism”—a moment in which video games both model and train us for functioning in the real world of economic relations—Porter’s act of détournement seems especially hopeful, thanks to her capacity to transform base commodities back into objects of wonder, and to turn images of work against themselves and back toward the ends of art.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her new book, Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts, was published by Badlands Unlimited in May 2018. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns, and editor of two forthcoming volumes: Making It Modern: A Linda Nochlin Reader, and Writing in Space: Lorraine O’Grady, 1973–2019.