Mark Polizzotti

Mark Polizzotti

Guitar heroes: a look back at Les Paul and Leo Fender.

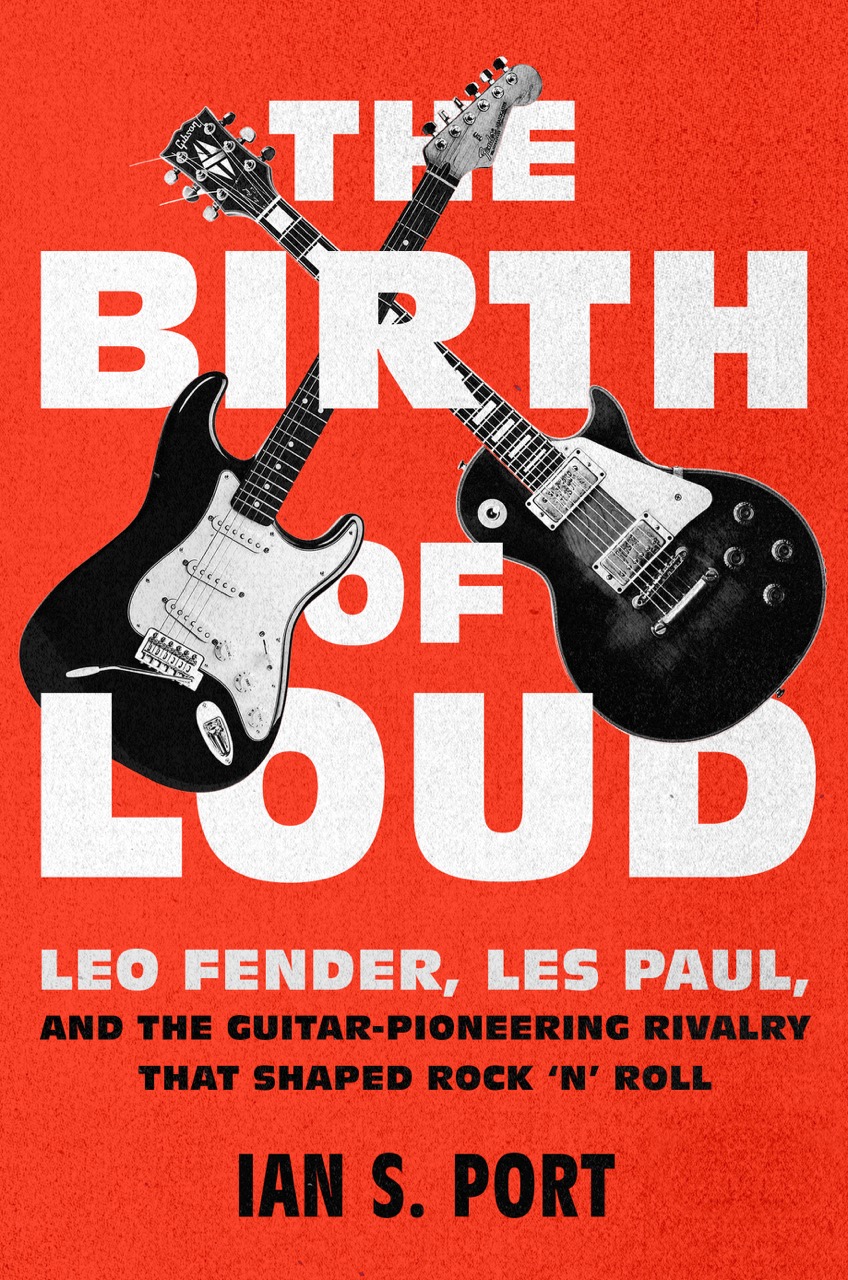

The Birth of Loud: Leo Fender, Les Paul, and the Guitar-Pioneering Rivalry That Shaped Rock ’n’ Roll, by Ian S. Port, Scribner, 340 pages, $28

• • •

Faced with the conundrum of writing about music without “dancing about architecture,” many, myself included, have simply blustered ahead, attempting, come what may, to explain why a given song or album is so (your adjective here). Others have offered up bios of the artists, producers, moguls, and love interests behind the catchy tunes. More recently, a third option has leapt onto the table: profiles of the instruments and instrument-builders that have made the music possible—an option somewhat less prone, at least, to the hyperbole that can dog the first two like screeching fans.

Ian S. Port’s The Birth of Loud presents a dual portrait of two men, Clarence Leonidas (“Leo”) Fender and Lester Polsfuss, a.k.a. Les Paul, whose names have become nearly synonymous with rock ’n’ roll. More to the point, it is a dual biography of the electric guitars that bear those names, whose distinctive tonalities, looks, and “auras” continue to define how we think of rock music, not only its sound but also the outsized images and innovations that have been central to its history.

Port, a music journalist, couldn’t have asked for better subjects, as Leo and Les form a god-given study in contrasts. Fender was quiet, frugal, averse to publicity, happiest when tinkering in a backyard shed in his overalls, and not himself a musician. An autodidact, he eventually expanded his hobby into one of the world’s largest guitar manufacturers (second only to Les Paul’s sponsor, Gibson), but his life was remarkable for its lack of remarkableness. Paul’s, on the other hand, was filled with drama, including a near-fatal accident just as his recording career was taking off and an extramarital affair with the young singer and guitarist Mary Ford—whom he then pushed into depression and alcoholism with his insistence on a punishing schedule of dates. He was gregarious, a virtuoso musician avid for stardom, more at home on society stages dressed in a tux than at a worktable. The two men’s guitars bespoke a similar divergence: while Les Pauls were manufactured to exacting old-world standards, a gentleman’s instrument, Fender’s goal—with such now-ubiquitous models as the Telecaster, the Stratocaster, and the Precision Bass—was to produce an inexpensive, easily repaired workhorse within every player’s reach.

In the end, Fender died a multimillionaire at age eighty-one, having sold his company to CBS decades earlier (making him, as one historian quipped, “one of the first people to get rich off rock ’n’ roll”). Paul, meanwhile, fell into near-obscurity after his peppy guitar stylings faded from vogue; his fame was ultimately restored by rock icons like Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, and Eric Clapton, who raised his guitar to cult status, even though he didn’t much care for their music. (For that matter, neither did Fender, who had spent his life trying to eliminate distortion and couldn’t understand why the longhairs intentionally courted it.)

The Birth of Loud is not the first book to describe the fabled rivalry of Fender vs. Paul. Les himself, ever craving the spotlight, published his own account in 2005, following Mary Alice Shaughnessy’s authoritative biography from 1993. Fender, more modestly, only gave interviews, but a biography of him (coauthored by his widow) was published in 2017. In addition, the guitars’ histories are related in such volumes as Richard R. Smith’s Fender: The Sound Heard ’Round the World (1996), Steve Waksman’s Instruments of Desire: The Electric Guitar and the Shaping of Musical Experience (1999), and Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound, and Revolution of the Electric Guitar by Brad Tolinski and Alan di Perna (2016). What The Birth of Loud does provide is the most comprehensive account to date of these two pioneers, while mercifully avoiding gearhead-level doses of minutiae. Written in pleasantly workmanlike prose, the book features some nice turns of phrase, though occasionally it also suffers from a rather breathless tone (“Doubt now filled Leo like his pens and tools filled his breast pocket”) and—a pet peeve—sloppy editing: “iconic” used twice in four lines, the guitars seeming to come “from outer space” over and over, “raving” (instead of “rave”) reviews, and so on.

Where I find the book most valuable is in its first-hand details, many of them culled from the author’s interviews with key figures, and in its debunking of some long-held myths—not least, the canard that Paul invented the Les Paul model, whereas it was designed and built by Gibson technicians and named after him as part of an endorsement deal. Port also highlights various individuals who were central to the evolution and promotion of these guitars—the salespeople, craftspeople, and early-adopter performers who not only brought the weird-looking creations to public notice, but helped improve them through their own enhancements and musicianship. In particular, he gives credit to the overlooked figure of Paul Bigsby, who might well have invented the first solid-body electric (on a design sketched out for him by country singer Merle Travis). And he finishes with a useful accounting of Fender’s and Paul’s actual achievements and legacies—which in Paul’s case include some very real innovations in recording technology, such as overdubbing.

Products “of the age of home inventors and backyard tinkerers,” Fender and Paul lived long enough to see the world they’d helped bring about grow alien to them: as Port nicely puts it, the guitars “had far outlived the dreams of their makers.” The country-western and jazz pickers the two men hung out with, and for whom they kept trying to develop better, cleaner-sounding instruments, gave way to a horde of raucous, feedback-loving ravers whose sounds and images, often with a Les Paul or a Strat firmly in hand, helped redefine popular music, and with it the attitudes of entire generations. Still today, those of us who persist in dancing about architecture are likely doing it to the sounds of Leo and Les.

Mark Polizzotti’s books include Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995; revised ed. 2009), Bob Dylan: Highway 61 Revisited (Bloomsbury, 2006), and Sympathy for the Traitor: A Translation Manifesto (MIT Press, 2018). He has translated over fifty books from the French, including works by Patrick Modiano, Gustave Flaubert, and Marguerite Duras, and his essays and reviews have appeared in the New York Times, New Republic, Bookforum, Wall Street Journal, The Nation, Parnassus, and elsewhere. He directs the publications program at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.