Margaret Sundell

Margaret Sundell

An anthology collects the Village Voice art writing of Gary Indiana.

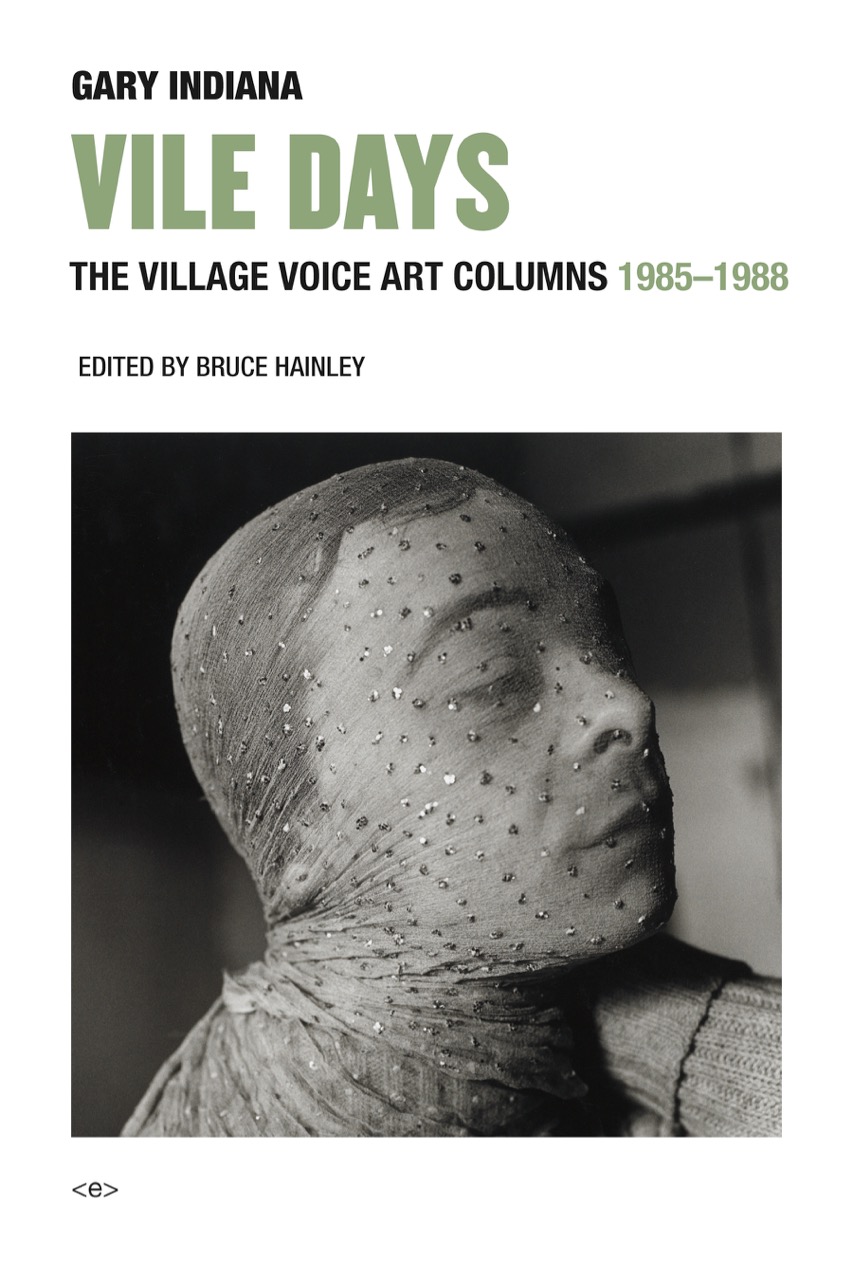

Vile Days: The Village Voice Art Columns 1985–1988, by Gary Indiana, edited and with an afterword by Bruce Hainley, Semiotext(e), 595 pages, $29.95

• • •

“To justify its existence, criticism should be partial, passionate, and political.” This injunction, which appears in the mission statement of 4Columns, was penned by Charles Baudelaire in 1846. But to anyone interested in art and reading the Village Voice in the mid-to-late 1980s, Baudelaire’s words can’t help but bring a second writer to mind: Gary Indiana, who served as the senior art critic of the storied weekly from 1985–88 and whose columns have been lovingly anthologized by Bruce Hainley in the recently published Vile Days.

What does it mean to consider Indiana, a novelist and playwright by trade, as an heir to the great French poet-critic? Not just that his columns were beautifully written; although, indeed, they were. Take his description of Kurt Schwitters’s collages as the “rescue of an exploded world’s passing debris,” or his characterization of Robert Mapplethorpe as an artist who “combines a preternatural refinement with an insatiable appetite.” His analysis of the now-forgotten Georgia Marsh arrests in its eloquence: her “landscapes deliver emotion gradually, like a Chopin étude, drawing one into a faintly deepening sadness, or a slowly numbing grief that this moment now already is becoming then.”

But the Baudelairean poet-critic is something more than a master of language: he is the writer charged, since antiquity, with conveying humanity’s noblest and most profound experience now forced to comply with the base imperatives of the fourth estate—its deadline-driven tempo, constraints of word count, demands of house style. In Indiana’s case, this tension results in a singular collision of high and low. Indiana elegantly elucidates contemporary art via an impressive range of philosophical and literary concepts. But then there are things like the Debbies (read debutantes; read Debbie Reynolds)—denizens of a “happy planet” who absconded from outer space to descend upon the galleries of a suddenly chic East Village. In Indiana’s prose, the Debbies appear breezily alongside Borges and Barthes, Freud and Flaubert.

Equally important, Indiana shares Baudelaire’s tendency to spleen. (An affinity Hainley notes in the book’s compact afterword.) And there was much in the mid-to-late-1980s to rouse his melancholic ire; for starters, that Debbie-infested gallery scene whose apex coincided with Indiana’s tenure at the Voice. As he scathingly observes, it was “an insignificant hiccup in the long burp of art history that created a seismic shift in the history of New York property values.” The writer has yet to forgive the gallery-led gentrification that destroyed his spiritual home: a bohemian enclave that flourished in the East Village, due in no small part to dirt-cheap rents.

The work shown in those galleries was also subject to his harsh scrutiny, especially the paintings known as neo-expressionist. Their monumental scale and lashing brushwork self-consciously evoked the “triumph of American painting” (to quote a phrase coined by art historian Irving Sandler) achieved by the likes of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. In Indiana’s view, “the mythos, and the bombast, have simply been leeched out of Abstract Expressionism and poured into neo-Expressionism.” But if Pollock and company starved for their aesthetic convictions, their 1980s avatars quickly grew rich in a new, corporate-backed art market.

Not surprisingly, Indiana detested these painters. To their macho grandstanding and seemingly soul-bearing angst, he countered and championed those mostly female practitioners who used photography and appropriation to interrogate the workings of power in an increasingly media-saturated society—Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Sherrie Levine, and Richard Prince chief among them. “The new photographic art,” Indiana extolled, “defines itself as an active, critical practice. It invites the viewer to evaluate pictures in terms of meaning and function instead of purely aesthetic gratification.”

But lest you think Indiana’s admiration is reserved for an art of critique, read his heartbreaking review of Ross Bleckner’s 1986 show at Mary Boone/Michael Werner. Bleckner’s poignant, mysterious paintings feature radiant motifs that are inscribed onto the canvas and then submerged in layers of paint, which obscure but fail to extinguish their smoldering presence. The objects depicted seem, in Indiana’s words, “to be crumbling apart; specks of brilliant luminosity suggest their imminent extinction.” The critic homes in on a series of canvases each featuring a trophy and a sequence of numbers, for example 8,122+ As of January 1986. As he explains, these pictures commemorate individuals who have died due to AIDS; Indiana lauds them as “brave acts of affirmation.”

AIDS, which ravaged the gay community in the 1980s—and by extension the art world—is the target of Indiana’s greatest spleen. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say that Indiana responded to AIDS with grief, and with fury at the paucity of medical research, public attention, and education that resulted in the AIDS crisis. “If you skim the papers this week,” he wrote in July 1986, “you’ll learn that an AIDS cure isn’t even being contemplated by ‘experts,’ because the condition hasn’t spread very dramatically into the white heterosexual population. If it ever does, it will become the nation’s health priority.” In fact, it was not until the following year, 1987, that President Reagan first uttered the word “AIDS” in a public speech. It is hard not to hear in his homophobic silence an intimation of our current administration’s effort to rescind the hard-earned rights of LGBTQ individuals.

The period Indiana describes had many parallels to our current one, and he nailed them with a prescience that is almost unnerving: the “liquidation of the middle class” effected by trickle-down economics, the “man-made ozone depletion” over Antarctica, “the scrambled quality of life in a media-jangled world.” Donald Trump, who was promoting his biography in 1987, even makes an appearance by way of a Vanity Fair photo spread. He “looks,” in the critic’s estimation, “like an especially virulent, shifty-eyed, loudmouthed accumulation of baby fat.”

In speaking truth to power, Indiana seems to be talking directly to us. Could his criticism serve as a primer for how to write about art now? This, I think, is an implicit question posed by the timing of Vile Days’ publication. Despite key differences between his moment and ours—the art world is no longer centralized in New York (or any locale); there are virtually no publications like the Voice (which folded this summer) to offer critics an ongoing, salaried platform—there is certainly much to learn from his example. Indiana analyzes; he never simply describes. He is unflinching in his views, but always open to being moved. He resolutely insists that art is made and seen by embodied beings—and that both it and they are enmeshed in broader political, social, and economic webs. He is partial, passionate, and political, indeed.

Margaret Sundell is the editor-in-chief of 4Columns.