Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Bodies hybrid and policed: two artists confront the corporeal.

Mandy El-Sayegh & Lee Bul: Recombinance, installation view. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin. Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein.

Mandy El-Sayegh & Lee Bul: Recombinance, Lehmann Maupin,

536 West Twenty-Second Street, New York City, through April 10, 2021

• • •

The title of Mandy El-Sayegh and Lee Bul’s joint exhibition at Lehmann Maupin—Recombinance—is well chosen, given the way both artists work at the troubled intersection of bodies and technology, an intersection located at the border between utopia and dystopia. The term is related to genetic engineering—manipulating DNA by combining strands from multiple sources. Like so many scientific advances, recombinant techniques can offer solutions to our most pressing problems; ready supplies of insulin, treatments for hemophilia, and even a number of COVID-19 vaccines all exist now because of such technologies. But they can also provoke fears about ethical abuses and unseen future effects, and can even cause the type of problems they are meant to allay: scientists are studying whether the COVID virus itself emerged through naturally occurring genetic recombination.

Lee Bul (born in 1964), who is based in Seoul, has for decades explored technology’s capacity to fulfill our wildest, science fiction–inspired dreams of perfection, as well as to create our worst nightmares when efforts to achieve such aspirations fail. She does this, often, via the figure of the cyborg—simultaneously human and robot, composed of elements of each—and through revisiting modernist architecture’s quest for the ideal machine for living. In both cases, she is attuned to the distance between the utopian impulses that motivate such imaginings—in which advancement is sought for the betterment of the common good—and the ways such technologies are most often put to use in our era: namely, to refine the individual without thought to, or even at the expense of, the collective.

While seeing deep resonances between their practices, the Malaysian-born, London-based artist Mandy El-Sayegh (born in 1985) observes, in an interview done on the occasion of this show, that where Lee Bul is interested in the body politic, and the body’s place within that societal formation, her own work grapples with questions of biopolitics—how bodies (and therefore political, social, and psychoanalytic subjects) are constituted and regulated through systems including surveillance and police identification techniques, medical imaging, political and economic structures, and language itself. It is both the similarities between Lee Bul’s and El-Sayegh’s work—the fascination with the body as fragment, the slippage between organic and inorganic—and the extreme formal differences that make the juxtaposition intriguing.

Mandy El-Sayegh & Lee Bul: Recombinance, installation view. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin. Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein.

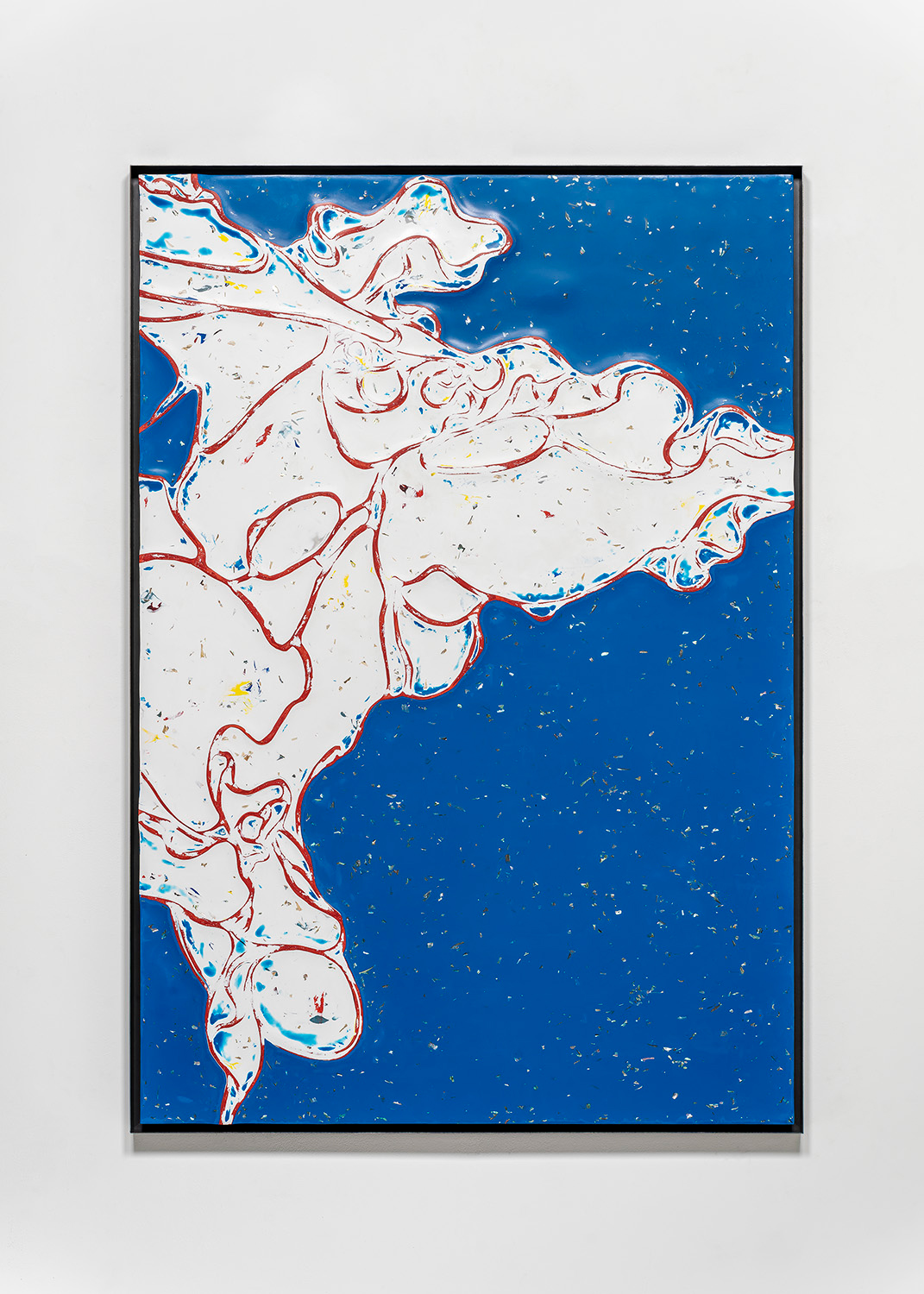

The bulk of the exhibition comprises works from Lee Bul’s series Perdu and El-Sayegh’s series Proofs, all done 2020–21, which are hung side by side in three rooms of the gallery. Though a departure from the medium for which she is best known, Lee Bul’s panels retain a sculptural feel: they are composed of acrylic mixed with mother-of-pearl chips applied thickly to a wooden support, so that the glinting mineral surface often ripples and bulges. We seem to be looking at a vast, dimensionless space, or a slide seen under a microscope. On these grounds float fragmentary forms that veer between biological and artificial—amoebas and cells and aliens and nanorobots and spaceships at once. They also suggest a body—a hybridized, cyborg body—coming into formation, assembling itself as it drifts through the void. Her choices of color—lemon yellow, ultramarine, grays, and blues in Perdu LXIX; forest greens in Perdu XLVIII; red, white, and blue in Perdu LXXIX; gold in Perdu XLVI—are surprisingly fresh and even hopeful. The forms are weird and creepy, but also beautiful, and somehow poignant—they are, if not lost (the English meaning of the French word perdu), then at least searching, moving toward completeness.

Lee Bul, Perdu LXXIX, 2021. Mother of pearl, acrylic paint on wooden base panel, steel frame, 62.99 × 43.31 × 2.36 inches. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin.

El-Sayegh’s Proofs are also about the fragmented body, though you might not think so at first glance. Made by silk-screening image and text and collaging layers on linen, they allude to the ways in which we are named and policed, proposing that if we push the state’s logics and methods for representing us to the extreme, our bodies will no longer be containable or legible. This is bodily abjection as a form of freedom, if we define freedom as a space beyond the reach of power. Here, El-Sayegh takes on identification through fingerprinting, substituting other parts of her anatomy, including, recurrently, her buttocks. Impressions of her bum, sometimes amended with pigment to suggest pie-nippled breasts, punctuate the Rauschenbergian ruckus visible underneath: pasted-on newsprint, silk-screened Arabic calligraphy (a language that the artist cannot read—it exists for her as a purely concrete, visual element), decontextualized words and numbers (some of which—“Sea Breeze,” “Susannah”—are code names for Israeli military operations, but set in carefully chosen typefaces that look more like consumer brand names), fabric, and repeated images of whimsical bunnies. The absurdity of El-Sayegh’s approach lays bare the vulnerability of fingerprinting and other taxonomic methods—keep impressing different body parts on surfaces and they cease to signify.

Mandy El-Sayegh, Proofs (six), 2021. Oil on silkscreened linen and collaged elements, 55.12 × 20.47 inches. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin.

The distinction between Lee Bul’s notion of corporeal fragmentation and El-Sayegh’s is key: Lee Bul thinks of fragmentation in a literal sense—as a body made up of parts—where El-Sayegh sees it as discursive—a body made up of intersecting discourses and forms of power. Where Lee Bul asks us to reflect on the possibilities—both of transcendence and of horror—that a post-human, cyborg future might hold, El-Sayegh pursues ways to make the body incoherent to the discourses that constitute it, not as a new mode of existence but as a necessary stage in rebuilding the subject beyond the power of the state.

Mandy El-Sayegh & Lee Bul: Recombinance, installation view. Courtesy Lehmann Maupin. Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein.

Take for example, El-Sayegh’s estimated at XX, a floor work in Lehmann Maupin’s second gallery composed of ninety-one latex-covered collages, each measuring approximately twenty-three by thirty-nine inches—the size of a human torso, the artist tells us. Your feet slip and squish a bit as the latex membranes—colored in rusts, reds, orangey-pinks, ferrous blues, and bilious greens—move and even tear underneath your steps. Look carefully and you will recognize below the rubbery surface layers upon layers of newspaper articles ripped from the Financial Times and the South China Morning Post, medical illustrations, ads for luxury goods, bits of textiles gathered from her family, calligraphic studies of Arabic lettering by her father, and other printed matter. It is as if you were traversing the flayed skin of an entity whose flesh and bone are an accumulation of detritus ripped so entirely out of its context as to become meaningless. This body makes no sense, which is precisely El-Sayegh’s goal.

Lee Bul, Untitled (Anagram Leather #6), 2004/2018. Leather covered hand-cut polyurethane panels on aluminum armature, stainless steel, and stainless steel wire, 67.72 × 30.31 × 10.63 inches. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin.

It is a peculiar comfort, then, to look up and see Lee Bul’s Perdu XLVII hanging on the back wall, a mashup of tibiae and mandibles and vertebrae and goo, or see, suspended in the doorway, her Untitled (Anagram Leather #6) (2004/2018), looking halfway between a homemade prosthetic and a side of beef. There is something viscerally convincing about El-Sayegh’s work, and about her evocation of what it is to be an embodied figure that lies beyond prevailing regimes of signification—but it’s a terrifying prospect, too, one that offers no promise for the future. I don’t know about you, but I’d rather take my chances with the robots.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. She is co-curator of Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And at the Brooklyn Museum of Art; editor of Lorraine O’Grady’s book Writing in Space, 1973–2019 (Duke University Press, 2020); and a member of the advisory board of 4Columns. In 2020, she received a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant for short-form writing.