Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Towards the New Baroque of Voices: a cinematic essay embodies Édouard Glissant’s “poetics of Relation.”

Manthia Diawara: Towards the New Baroque of Voices, 2021, installation view. Photo: Shark Senesac. Courtesy Amant.

Manthia Diawara: Towards the New Baroque of Voices, Amant,

306 Maujer Street, Brooklyn, through January 30, 2022

• • •

Manthia Diawara’s Towards the New Baroque of Voices (2021)—a 115-minute cinematic essay composed largely of existing footage of thinkers and artists, shot over decades of the filmmaker’s career—begins with Édouard Glissant. The Martiniquais poet and philosopher makes the bold statement that democracy renders colonialism impossible. The implication, he goes on to explain, is not that what we have seen from Western powers isn’t colonialism—but rather that it isn’t democracy. The West has traded the appearance of democracy—the spectacle of it, even—for democracy itself. What’s worse, they’ve imposed that ersatz vision on formerly colonized states, who were forced to embrace it as a condition for freedom from their colonizers.

The lesson here, in Glissant’s words and in Diawara’s framing of them in his compelling film, is an especially important one for those of us watching as the US Congress wrangles over protecting voting rights and prosecuting the January 6 seditionists. Many ask if we are seeing the death of democracy. But Glissant insists that in fact we’ve hardly seen the birth of it, because just at the moment of its appearance in revolutionary France it was “formalized and frozen.” (One thinks of the human specimens in Paris’s Musée de l’Homme—fetuses in jars, etc.)

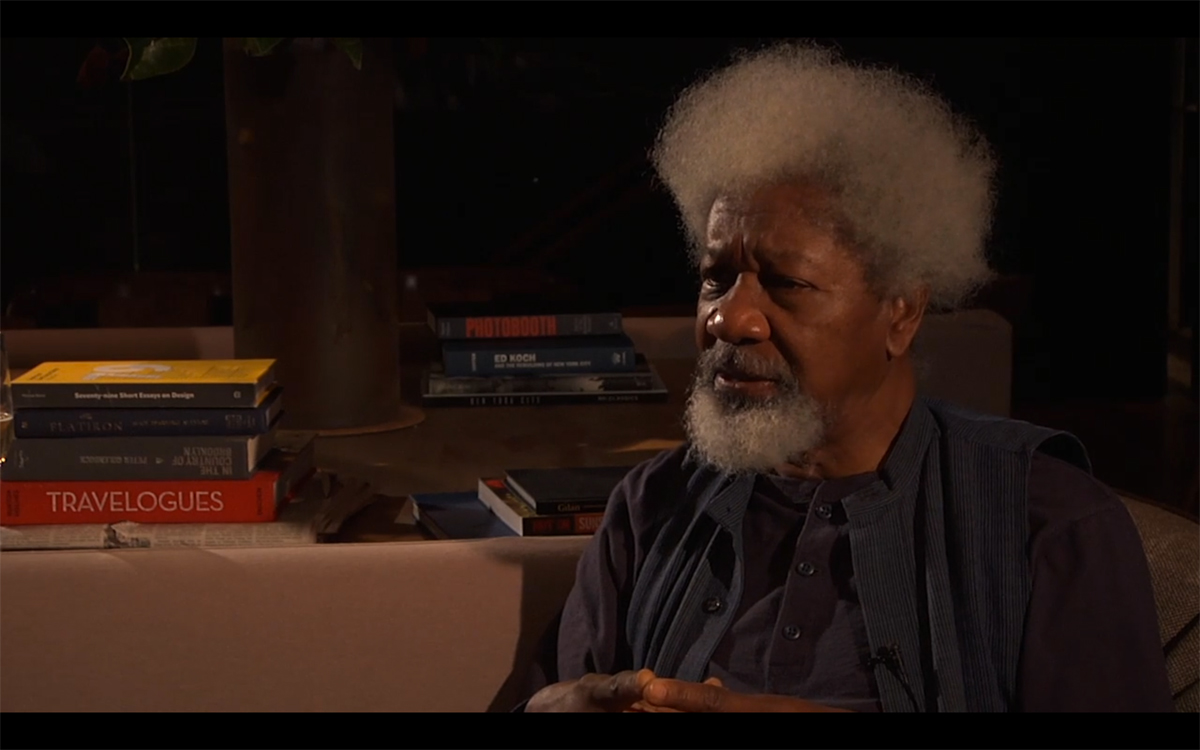

Wole Soyinka in Negritude: A Dialogue Between Soyinka and Senghor, 2015, excerpted in Towards the New Baroque of Voices, 2021.

On view now at Amant, which coproduced it with the 34th São Paulo Biennial, Towards the New Baroque of Voices is many things at once: among them, an assessment of the current political situations in countries across Africa and their roots in history and an argument about the xenophobia inherent in European and North American policies toward immigrants. But perhaps most interestingly, it is a proposal about what democracy could be. Using the formal devices available to him as a filmmaker, Diawara takes seriously Glissant’s notion of a “poetics of Relation,” in which the world is produced through endless encounters between fully autonomous entities—people, cultures, even nations—allowed to retain their individual, essential qualities while finding grounds for solidarity with one another. (The title of the film alludes to this: in the Baroque period, vocal music abandoned the smoothness and roundness of Renaissance composition, allowing for different voices to remain distinct while contributing to a cohesive whole.) To make this argument manifest, Diawara has taken previously recorded interviews—including with the Senegalese writer and filmmaker Sembène Ousmane, the Nobel Prize–winning Nigerian author Wole Soyinka, the French ethnographic filmmaker Jean Rouch, the American actor and activist Danny Glover, the Malian author, politician, and activist Aminata Traoré, and many others—and edited them into a “conversation” after the fact, allowing their arguments to agree and contradict in turn.

Manthia Diawara: Towards the New Baroque of Voices, 2021, installation view. Photo: Shark Senesac. Courtesy Amant.

Like in almost all of Diawara’s work, the focus here is Africa. But so too is the question of diaspora. It is as if Africa cannot be discussed without thinking about its dispersal—or, as Glissant would have it, its errantry. Diaspora is evoked first by the sheer range of geographical positions from which Diawara’s subjects speak; it also emerges visually in recurrent images of the ocean taken on Diawara’s trip with Glissant on the Queen Mary II from England to Brooklyn, the basis of his 2010 film Édouard Glissant: One World in Relation. But other than this subtle nod to the Middle Passage, the cataclysmic disaster of the slave trade is hardly mentioned. The handful of African Americans in the movie—Glover, the director John Singleton, the artist David Hammons, and the self-described “grande dame of African American Paris,” Velma Bury—all come off as having more political passion than savvy (a familiar, and not always kind, treatment of African Americans in African film and literature). Glover speaks romantically about coming to Africa to find inspiration among people who have “empowered themselves” by reclaiming their history and story; we see him, before and after this clip, dancing with a little too much verve to the music of the Bembeya Jazz National—the dude has no chill. Diawara slyly cuts from Glover to the actress Binta Diallo, who says, “If I had a chance to express myself with the same access to science and technology as everyone else I would use my African identity to make myself better understood. And that would benefit everyone.” Then we see Glover dancing some more.

Manthia Diawara: Towards the New Baroque of Voices, 2021, installation view. Photo: Shark Senesac. Courtesy Amant.

These moments of dissonance and disagreement, of ambivalence and multivalence, are in some ways the most important in the film, interrupting any fantasy of clear consensus or easy alliance. One of the most devastating occurs in the third “chapter” of the piece, titled “Detours as Revolutionary Nostalgia.” (The others are “Decolonization,” “Nations, Borders, Modernity,” and “Opacity & Relation.”) The section centers on clips from Diawara’s 1995 filmic portrait of Rouch, founder of the cinema verité movement in France whose challenges to the tradition of ethnographic filmmaking have influenced many African artists, including Diawara himself. Rouch takes Diawara to see a statue honoring Jean de La Fontaine in Paris. The homage to the seventeenth-century fabulist includes a fox and a crow—characters from one of his poems that every French schoolchild is made to memorize. Rouch intones the first line—and then, in the most cringeworthy way possible, insists that Diawara complete the recitation, correcting the latter when he stumbles or forgets the precise wording. The sheer paternalism of the gesture undermines Rouch’s later claim that over the course of his career “I learned more from Africa than Africa learned from me.” Between Rouch’s two appearances we see figures like Rwandan human rights lawyer Alice Karekezi and Cameroonian writer Blaise Ndjehoya talk about their relationship to French literature, history, and political philosophy. In the most powerful of these accounts, and the only one by a working-class person, factory worker Djafodé Sacko speaks of the gap between the dream of France with its ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity that he learned about in school and the reality of his everyday life as an immigrant there. “I don’t want to abandon the dream,” he says, “because I find more pleasure in the dream than in reality.”

Manthia Diawara: Towards the New Baroque of Voices, 2021, installation view. Photo: Shark Senesac. Courtesy Amant.

Towards the New Baroque of Voices is shown on two screens placed at a slight angle to each other. What’s projected onto one screen does not merely illustrate what the talking heads are saying on the other, but rather intersects, contradicts, and illuminates the multiple perspectives. Some images recur: the signboard of the Hotel Independence, a sly reminder of the way democracy has been “branded” rather than fully realized; the wake of the Queen Mary II as it cuts through the Atlantic; marketplaces and artisan’s workshops in various African cities; skylines and aerial views of those same cities, which trade particularities for a unifying, and relatively untextured, sense of place. The most interesting of these scenes, though, is a traffic interchange, which we see both from above and a distance, as well as from street level. Cars jockey into lanes and people walk any which way. What some might view as the chaos of a “Third World” city, however, strikes one here as a remarkably useful way of organizing the world: everyone going in different directions and with different goals in mind, but getting to their destinations all the same.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. She co-curated the 2021 exhibition Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And at the Brooklyn Museum of Art and is the editor of a forthcoming collection of the writings of Linda Nochlin, Making It Modern (Thames and Hudson, 2022). She is also a contributor to the New York Times. She was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.