Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

In the artist’s project Seat Assignment, it’s air flights of fancy.

Nina Katchadourian, Lavatory Self-Portrait in the Flemish Style #13, 2011 (from Seat Assignment, 2010–ongoing). C-print, 10.42 × 8 inches. Image courtesy the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Pace Gallery.

Seat Assignment, by Nina Katchadourian, images available on the artist’s website and via a video presentation on YouTube

• • •

Editor’s note: In light of the fact that museum and gallery exhibitions remain closed during the coronavirus pandemic, we have invited our contributors to reflect on an artwork that is particularly significant to them and that is easily viewed online.

• • •

How to be creative in confined quarters with only the materials you have on hand for seemingly endless stretches of time? It’s a question that so many of us are grappling with in this moment of social distancing and shelter-in-place—and it’s long been a preoccupation of conceptual artist Nina Katchadourian, whose work has for many years been occupied with staving off boredom by discovering magic in the mundane. During a flight to Atlanta in 2010—before you could count on planes having Wi-Fi, when flying was a matter of getting into a metal tube and being cut off from earthly time between takeoff and destination—Katchadourian started to treat her cramped economy airline seat as a test of her belief that art could happen anywhere, as long as you were willing to pay attention and use your wits. Employing just what she found around her—the paltry snacks dispensed by hassled flight attendants, inflight magazines (including the SkyMall catalog), paper products culled from the lavatory, the stuff in her carry-on, and her camera phone—she began her ongoing project Seat Assignment.

Nina Katchadourian, Topiary, 2012 (from Seat Assignment, 2010–ongoing). C-print, 45.50 × 35.5 inches. Image courtesy the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Pace Gallery.

Seat Assignment is a study in resourcefulness and a superb demonstration of Katchadourian’s nimble mind. The countless photographs and videos that make up the larger body of work are grouped into a number of series. In Landscapes, the artist places various foodstuffs on top of the seductive travel photos from the inflight magazines—photos calculated to get you to fly more, to ever more exotic destinations—to transform them into fantastic, even alien planets. For Buckleheads, she photographs the reflections of nearby passengers in the polished surface of her seatbelt clasp; by turns distorted and uncannily clear, these faces become a record of the spaced-out boredom that Katchadourian’s project is designed to sublimate. She has a bit of puerile fun with Top Doctors in America—that multipage advertorial that is a fixture of airline publications—by giving the medics beaks and horns and other facial protrusions using peanuts and orange peels and chewing gum, mutating them into figures that are simultaneously demonic and hilarious, like characters from Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Nina Katchadourian, Bucklehead #1, 2011 (from Seat Assignment, 2010–ongoing). C-print, 15.25 × 19 inches. Image courtesy the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Pace Gallery.

As with a lot of Katchadourian’s work, there is often pathos lurking underneath the humor and inventiveness. Disasters is funny at times—crushed-up pretzels strewn over images of highways and bridges read as carb-loaded rock slides. But when she sprinkles black powder on a photo of a Delta jet, as if one engine were burning up, or pokes her finger through images of airplane windows or cockpits, as if the contraption were being grabbed by the hand of god (or some creature less benign), or stands two wafer cookies on end and photographs them from above, so they look like nothing less than the towers of the World Trade Center before they were laid low, we see a trace of the anxiety that adheres to travel in the post-9/11 era.

Nina Katchadourian, Engine Failure, 2011 (from Seat Assignment, 2010–ongoing). C-print, 19 × 24 inches. Image courtesy the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Pace Gallery.

In a catalog essay from 2011, Katchadourian notes that the pictures in Seat Assignment “often fall into three of the most timeless art historical genres: still life, portrait, landscape.” Indeed, while her altitudinal efforts offer plenty of visual jokes, they also contain lots of shrewd references to the history of art making. The most famous of these—and the ones that are getting the most attention now, as museums around the world encourage housebound art lovers to recreate their favorite artworks at home—are Katchadourian’s Lavatory Self-Portraits in the Flemish Style. After spontaneously deciding to lock herself in the toilet to play dress-up with paper products on a domestic flight, which resulted in the first photo in the series, she expanded on the prototype during a long-haul trip. Toilet seat covers, paper towels, an eye mask, a neck pillow, and a disposable cup she gleaned on the plane, along with her deadpan expressions and distinctive poses, transfigure her—quite remarkably—into characters that would be at home in paintings by Robert Campin or Rogier van der Weyden or Jan van Eyck.

Nina Katchadourian, Rapture, 2011 (from Seat Assignment, 2010–ongoing). C-print, 24 × 19 inches. Image courtesy the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Pace Gallery.

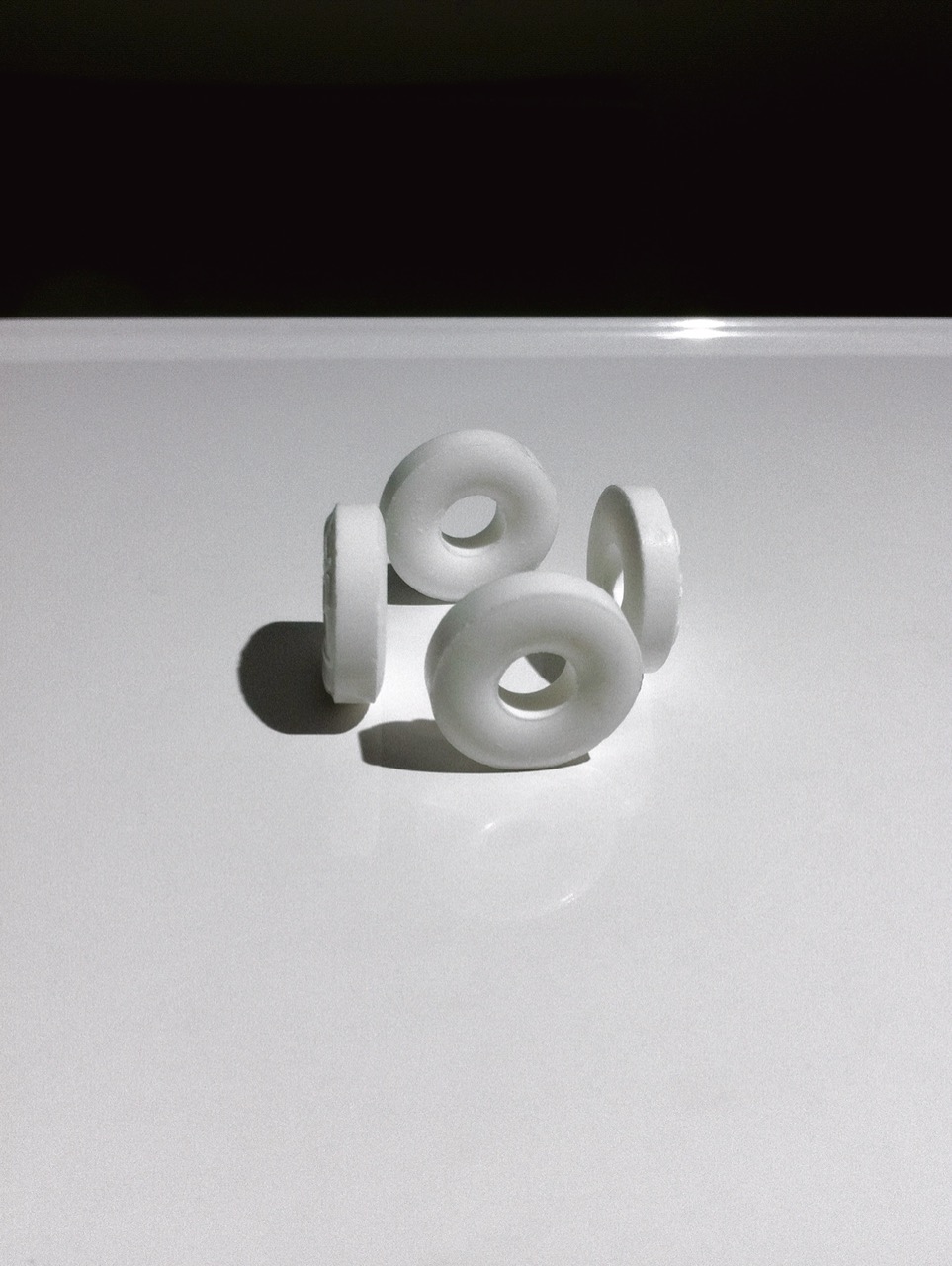

But Katchadourian’s engagement with art history goes well beyond a one-liner. High-Altitude Spirit Photography nods to late-nineteenth-century attempts to capture spectral presences via the new technology of the camera by shooting the glare on glossy magazine pages. By placing bits of orange peel on a photo of a sports field or standing Life Savers candies on their sides, she creates Proposals for Public Sculpture. (In these and many other works in Seat Assignment, disjunction of scale is one of her most valuable formal tools.) Her snapshots of airplane wings, with the seams and rivets of their metal cladding and the decals of arrows and safety stripes, are reimagined as abstract compositions in the style of Rodchenko and Malevich in Window Seat Suprematism.

Nina Katchadourian, Sun Tunnels, 2012 (from Seat Assignment, 2010–ongoing). C-print, 19 × 15.25 inches. Image courtesy the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Pace Gallery.

When Katchadourian first showed these works in 2011 at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery in New Zealand, two of the three galleries were filled with images she created on her twenty-plus-hour journey from New York to New Zealand. That time constraint, along with the other limitations she placed on herself—a refusal to use a fancy camera or special lighting, or to pack anything in her carry-on dedicated to inflight image making—and the limitations of working in a semipublic space where other passengers or the flight crew might question what she was doing, force a different kind of creativity than that of the artist’s studio.

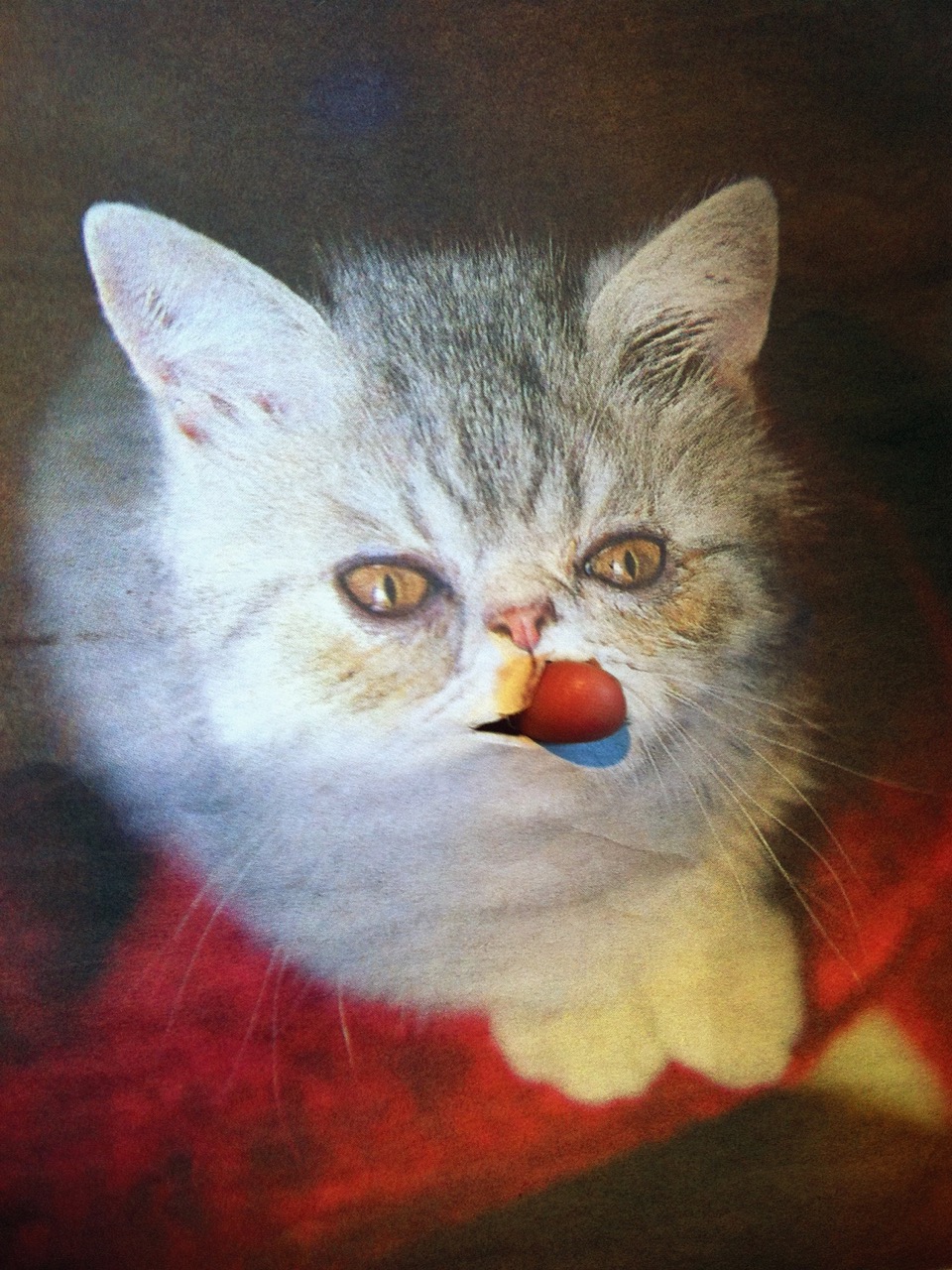

Nina Katchadourian, Evil Kitten, 2013 (from Seat Assignment, 2010–ongoing). C-print, 19 × 15.25 inches. Image courtesy the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Pace Gallery.

Life for some in the coronavirus world seems to be a paradoxical coexistence of boredom and stress. Those of us who are lucky enough to be able to shelter in place are faced with the pressure to be productive—to continue our jobs remotely, to school our children, to care for those who are ill, and to do so without many of the conveniences that made our work and lives possible, squeezed into small spaces with other people twenty-four seven, six weeks and counting, or alone, trapped inside our four walls and our minds, and even, as a current meme exhorts us, to follow in the footsteps of Isaac Newton, who discovered gravity while in quarantine during the plague. Katchadourian’s work offers a welcome alternative. Instead of being productive, she asks us to lean into the boredom, and there to rediscover the pleasures of play.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. She is co-curator of Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And, an upcoming retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum of Art; editor of Lorraine O’Grady: Writing in Space, 1973–2019 (Duke University Press, 2020); and a member of the advisory board of 4Columns. In 2020, she received a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant for short-form writing.