Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

From Flo Jo’s nails to splashing in soda pop: a show of BLAXIDERMY.

Pamela Council: Bury Me Loose, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Denny Dimin Gallery.

Pamela Council: Bury Me Loose, Denny Dimin Gallery, 39 Lispenard Street, New York City, through October 23, 2021

• • •

At Denny Dimin Gallery, the multidisciplinary artist Pamela Council told me that the work in their new solo exhibition—the first since signing on with the dealer—was “dark, maybe the darkest I’ve done.” That fact is certainly not obvious at first glance. The sculptures, videos, and assemblages here, made over the last decade, evince an exuberant, fit-it-all-in formal and conceptual energy and contain references to the poppiest of pop culture: the pinker, glitzier, plusher, femme-ier the better, it seems, for this artist. But, as Council remarked in a recent interview in Hyperallergic, “There’s a lot of camp in horror, there’s a lot of horror in camp.”

Pamela Council, Flo Jo World Record Nails, 2012–21. 2,000 acrylic fake fingernails, nail polish, rhinestones, metal, wood, 22 × 60 × 40 inches. Courtesy the artist and Denny Dimin Gallery.

Council’s aesthetic approach reflects this dialectic. They call it BLAXIDERMY, a portmanteau of “Blaxploitation” and “taxidermy” that evokes ideas ranging from Black cultural joy to the exploitation of Black people as spectacle to the all-too-present specter of Black death. One early foray into this visual language is Flo Jo World Record Nails. First created in 2012, and then entirely remade during the past year and a half of lockdown, the piece pays close, reverent attention to the late Olympian Florence Griffith Joyner’s unapologetically Black style on the track, where she won countless gold medals and set world records in the one hundred– and two hundred–meter events. The runner bucked convention with her asymmetrical, vividly colored, one-legged tracksuits, full makeup, and—most famously—her exquisitely manicured, long fingernails (she worked in a nail salon while trying to qualify for the Olympics). In homage to the star athlete—who was at once celebrated for her achievements, deemed unsportswomanlike and inappropriate for her self-presentation, and dogged by rumors of steroid use despite never failing a test—Council hand-painted three hundred sets of acrylics to match the red, white, blue, and gold stars-and-stripes designs Flo Jo wore at the 1988 games. Two thousand of these were assembled on metal supports mounted to a wood panel in a one-to–one hundred scale model of a two hundred–meter track that twists and arcs upward, as if in flight. Ten sets of nails were turned into Flo Jo World Record Nails Boxed Set Edition (2012), packaged using a “Flo Jo” logo Council adapted from the one Mattel designed for that company’s Flo Jo doll.

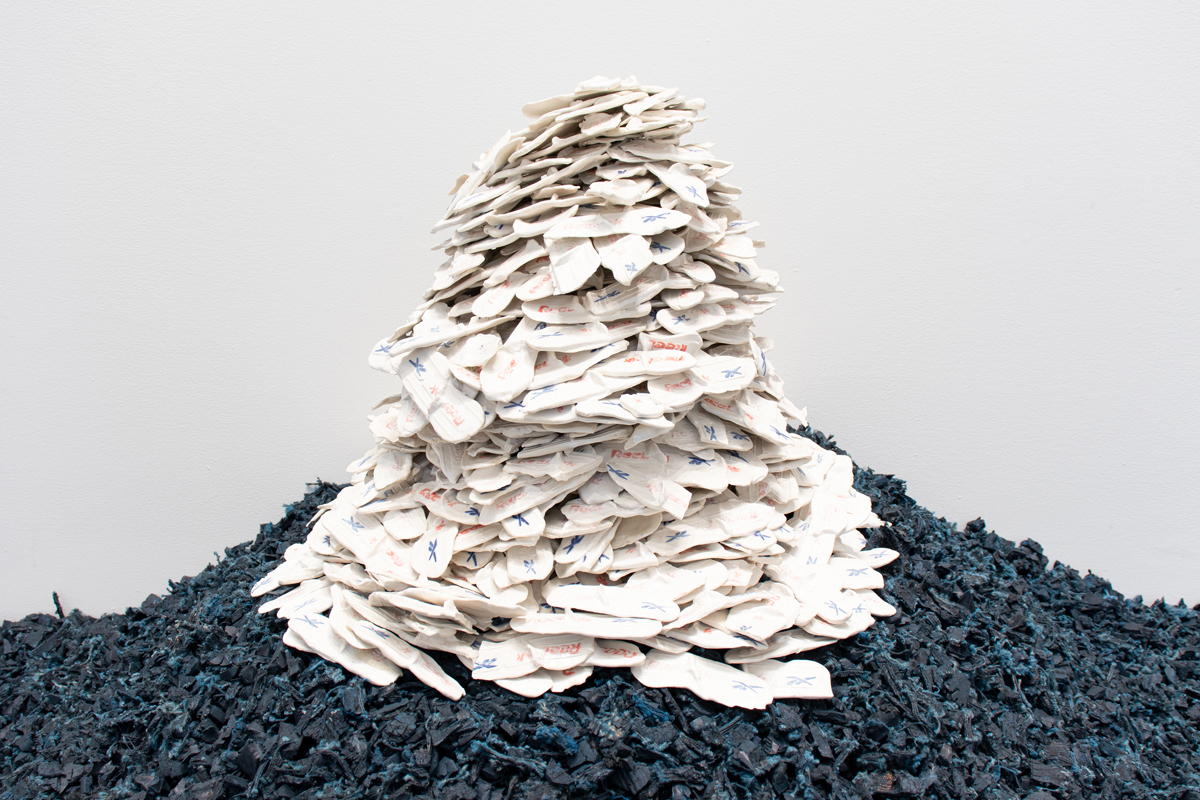

Pamela Council, Jumped Ship, 2013–21. Ceramic, 24 × 23 × 23 inches. Courtesy the artist and Denny Dimin Gallery.

Flo Jo World Record Nails is installed in the gallery’s front room among other investigations into sport and play, themes that have occupied the artist for some time. In Jumped Ship (2013–2021), a mound of handmade and glazed ceramic pieces that resemble running-shoe insoles, each stamped with a Reebok logo, lies on an area of floor covered with the kind of rubber chips used in children’s playgrounds. The title of the piece points to a variety of meanings: Council’s brief career at Reebok, where she considered becoming a sneaker designer; basketball jump shots; and, more troublingly, the stories of enslaved men and women who jumped to their deaths during the harrowing Middle Passage to claim the only freedom available to them—the freedom of death. (Those latter narratives are also alluded to in a print in the next room, Leap!, from 2020.) Hung on a nearby wall is the series Reliefs. Council hand carved reproductions of design samples she found in the Reebok archives, some of which were used in the manufacture of classic court sneakers; from these she cast silicone tiles, framing them in gridded arrays. The ivories and pale browns of the casts, their modular format and abstract patterns, and the simultaneous translucency and rubberiness of the material suggest both Minimalist art and the body—perhaps not simply the body, but the body subjected to a strange taxonomy, reduced to samples.

Pamela Council, Relief 20, 2021. Silicone tiles on wood panel, 18 1/4 × 18 1/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Denny Dimin Gallery.

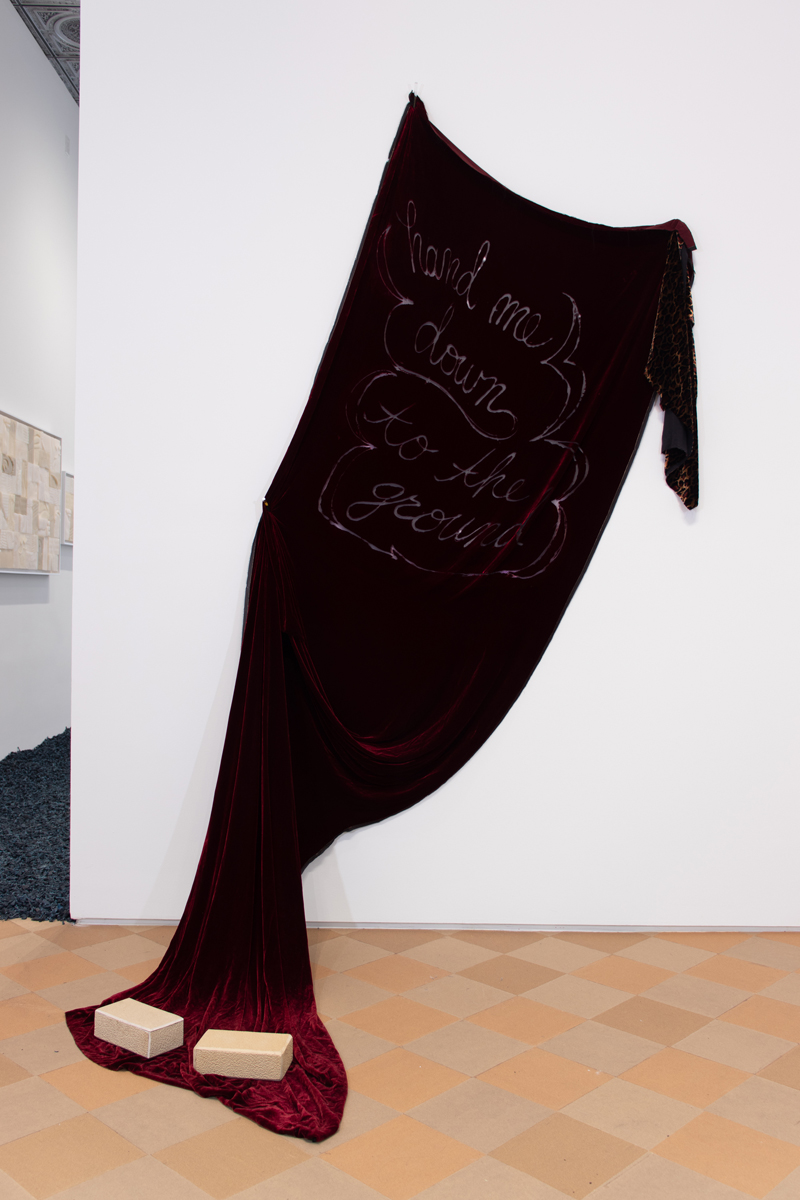

Elders are present in the show, with all of the ambivalence that attends family relationships. Hand Me Down to the Ground (Auntie) (2015) is a silk velvet banner attached to the wall of the gallery’s second room with metal and glass crack pipes that function as nails—an allusion, perhaps, to the drug and the war on drugs that devastated a whole generation of Black aunties and uncles in the 1980s and 1990s. Burned into the fabric are the poetic words of the title—alluding to handed-down knowledge, but also the way that knowledge can lay the receiver low. In a small niche a monitor shows a video related to Council’s sculpture Red Drink: A BLAXIDERMY Juneteenth Offering (2018). Red Drink was an almost-cartoonish fountain organized around a stylized palm tree and containing eight hundred gallons of Big Red soda, which Council has described as a “dedication” to a recently deceased uncle who died a very traumatic death. Viewers were invited to drink a toast to freedom and make an offering of soda pop to their ancestors. In the video, Council splashes in the fountain while wearing a GoPro camera, partaking in what they refer to as the “Sticky-Sweet-Nostalgic-Restorative!” experience of the work.

Pamela Council, Hand Me Down to the Ground (Auntie), 2015. Silk velvet, Rubber bricks, crack pipes, 100 × 46 × 24 inches. Courtesy the artist and Denny Dimin Gallery.

Council’s ring holders are mounted on shelves along one wall of this space. These small sculptures, molded out of dollmakers’ Sculpey (or, in one case, in porcelain), perch on small pedestals and nestle in velvet-lined boxes of the kind used in jewelry stores to display pricey engagement rings. On their website, Council writes that they “started this series for all the times mi fadda brought the patriarchy up in my face, talkin bout ‘when you gettin married?’ when he knows good n well I’m not about that life . . .” The ring holders are a hilarious retort to paternal pressure; Council uses the strangely near-but-not-quite-lifelike material to fashion things that might be body parts—tongues, labia, clitorises, earlobes—sometimes delicately adorned with rhinestones and nail polish. They are seductive and tacky and a little gross, like most of the human body is, when you get right down to it.

Pamela Council: Bury Me Loose, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Denny Dimin Gallery.

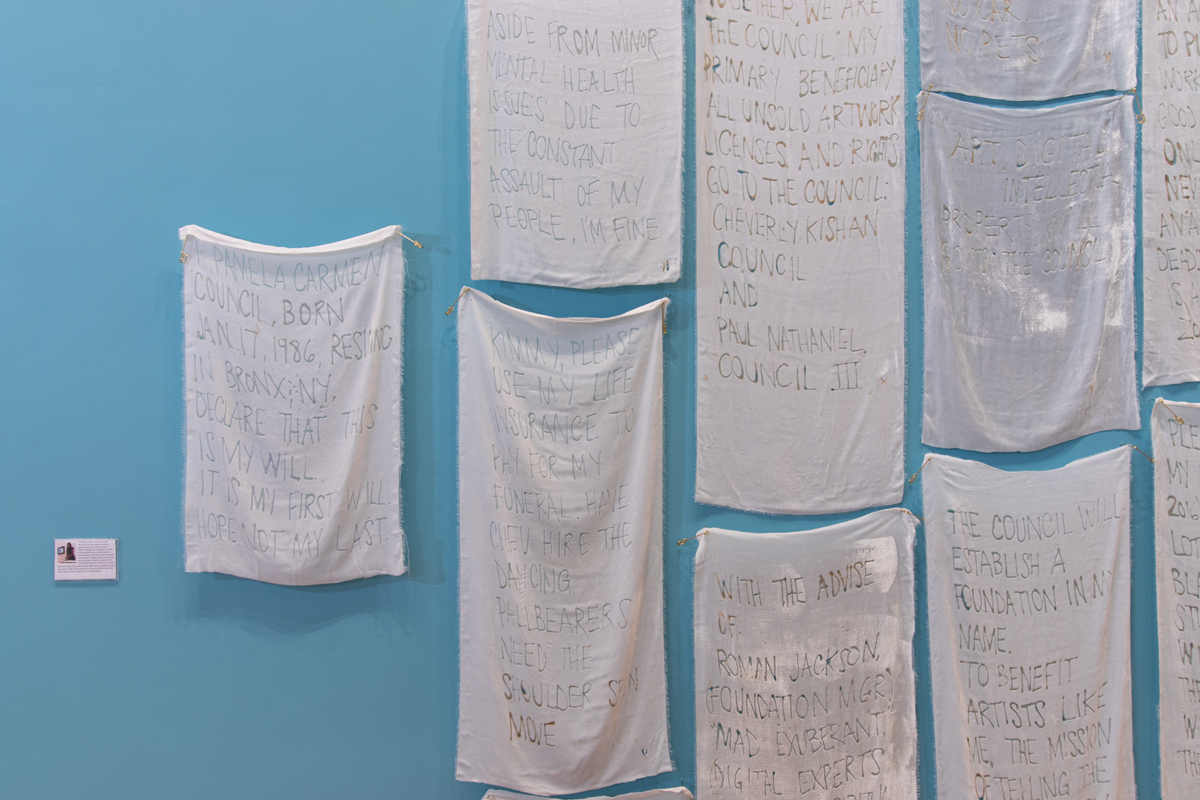

Nearby is Velvet Will, a piece that originated as the live performance Is Your House in Order, the last iteration of which was organized by Black Art Incubator at Recess in 2016. The work was inspired by the fact that many African Americans don’t leave formal instructions for how to disperse their estates—estates that are overwhelmingly, it must be said, a fraction of white Americans’ thanks to many generations of wealth-stripping experienced in the wake of Emancipation. In response, in the 2016 performance, Council broke out an iron and ironing board and burned the terms of their will into twenty pieces of silk velvet. The text is poignant and hilarious: to their executor, they write, “First, if I die, find out why. Aside from minor mental health issues due to the constant assault of my people, I’m fine” and “Use my life insurance to pay for my funeral. Have Chev hire the dancing pallbearers. Need the shoulder spin move.” They assign licenses and rights for their artwork to their siblings. They also ask that their annual donation of lotion “to the Black art students of Williams Coll. [their alma mater]” be maintained and that a Black makeup artist prepare their corpse, in both cases to avert the inexcusable condition of ashiness.

Pamela Council, Velvet Will, 2016 (detail of installation view). Silk velvet, big safety pins, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Denny Dimin Gallery.

The title of Council’s exhibition is Bury Me Loose—a phrase that comes from a viral tweet that circulated earlier this year. User @yedoye_ wrote “damn a coffin costs $4000??? y’all can bury me loose.” The quip is a startlingly insightful punch in the gut: in the middle of a pandemic, when living seems impossible thanks to white supremacist capitalism and its ills—when Black people have been dying in inordinate numbers thanks to disparities in health status, access to health care, wealth, employment, wages, housing, income, and poverty—not even death is a viable escape: even if you jump ship, so to speak, someone is going to get a bill. Like @yedoye_, Council responds to this horror the only way possible: with a kind of campy, acid humor that plumbs untold depths of pain, trauma, and history.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. She co-curated the 2021 exhibition Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And at the Brooklyn Museum of Art and is the editor of a forthcoming collection of the writings of Linda Nochlin, Making It Modern (Thames and Hudson, 2022). She is also a contributor to the New York Times. She received a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant for short-form writing in 2020 and was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.