Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Finding the foreign—and finding solidarity: an exhibit curated by Adriano Pedrosa locates complexity and context in the movement

of artistic journeys.

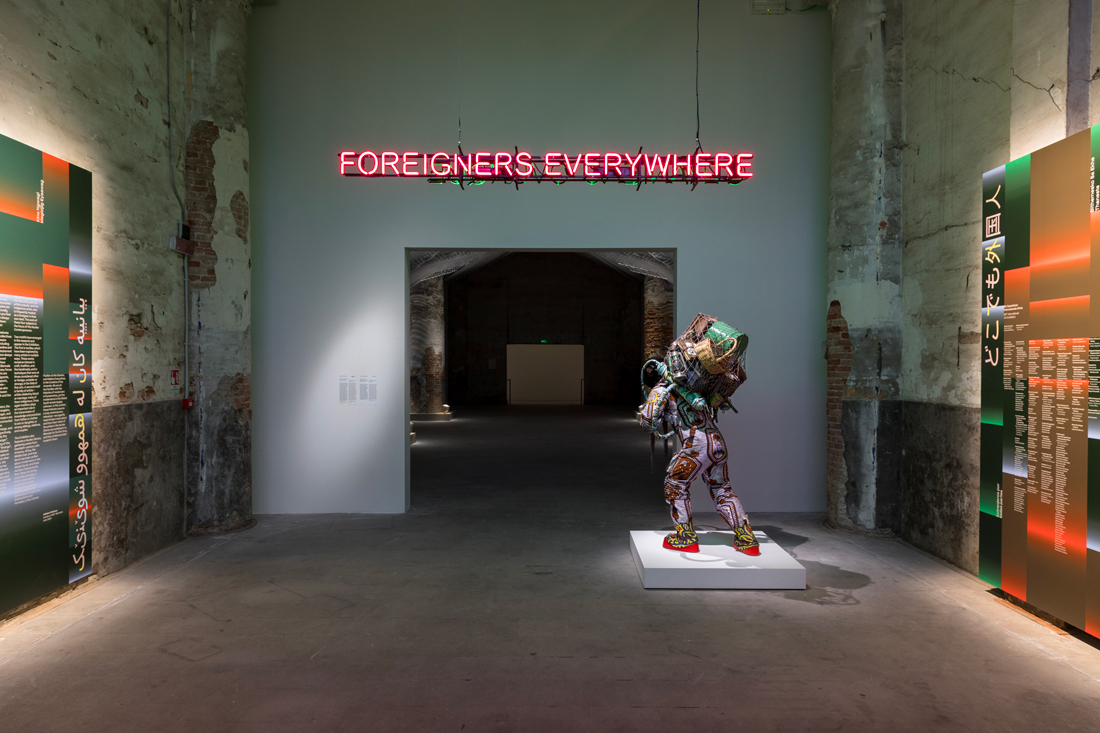

Claire Fontaine, Stranieri Ovunque (Autoritratto), Foreigners Everywhere (Self-portrait), 2024. Double-sided, wall-mounted neon, framework, transformers, cables, and fittings. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Marco Zorzanello.

La Biennale di Venezia 60th International Art Exhibition: Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, Giardini and Arsenale, Venice, Italy, through November 24, 2024

• • •

The title of Adriano Pedrosa’s curated exhibition at the Venice Biennale comes from a series of neon-light installations by the art collective Claire Fontaine, which is in turn the name adopted by a group of Italian activists protesting xenophobia in the early 2000s: Stranieri Ovunque, or Foreigners Everywhere. The phrase cuts many ways: as a statement of fact (the UN estimates that as of 2022 over a hundred million people could be identified as forcibly displaced); as an increasingly familiar xenophobic complaint in Italy and elsewhere; as a cry of distress from people who, no matter where they go, are always marked as other. For Pedrosa, the condition of foreignness is projected onto and embodied by not only those who are “immigrants, expatriates, diasporic, émigrés, exiled, or refugees,” but also queer artists, who have put paid to gender boundaries and have often been persecuted or outlawed for it; outsider artists existing at the edges of the art world, if they are admitted at all; and Indigenous artists, who are “frequently treated as [foreigners] in their own land.” The show’s 331 participants fall into these categories, ones that render their relationship to the organizing principle of the Biennale—the nation-state—tenuous, even precarious. The definition of “foreigner” here is so capacious that I was hard-pressed to imagine its opposite; one of the strengths of Pedrosa’s conceptual mapping is that anyone who experiences the show has the opportunity to understand themselves as a stranger in one sense or another, and, in doing so, to see possibilities for solidarity that would otherwise be occluded.

Mataaho Collective, Takapau, 2022. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Marco Zorzanello.

Only a few highlights can be noted here, though many are on offer. A series of galleries is devoted to the world-building storytelling and technologies of survivance of global Indigenous peoples (a category that productively seems to include customary African societies). This section is introduced by the Mataaho Collective of Māori women artists, whose installation Takapau (2022) employs modern materials to reference traditional weaving methods, utilizing high-visibility tie-downs (used to secure cargo to ships or truck beds), hooks, and stainless-steel buckles to construct an architecturally scaled and dramatically lit set of intersecting sails that cut through space. The title refers to mats used in childbirth—a moment of transition, in the Māori worldview, from the realm of light to the realm of the gods. Later on, Daniel Otero Torres’s structure Aguacero (2024) recreates a vernacular form of stilt building designed by Colombians living along the banks of the Atrato River to deal with the ironic lack of clean water in one of the most rainfall-abundant places on earth, the result of illegal gold mining.

Daniel Otero Torres, Aguacero, 2024. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Marco Zorzanello.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, the idea of gender disobedience is taken up to great effect by Sudanese-Norwegian artist Ahmed Umar’s hypnotic Talitin ثَالِتِن (The Third) (2023–24), in which he reenacts a Sudanese bridal dance that fascinated him as a child, but from which he was excluded after puberty, and by Mexican artist Ana Segovia, whose sumptuous video Pos’ se acabó este cantar (2021) homes in on the image of Mexican cowboys (charros). Simply by restyling the typical costumes of these iconic macho figures with fluorescent hues, she imbues them with a homoeroticism so intense that many tailors refused to take on her commission. A gallery featuring work by Evelyn Taocheng Wang, Nedda Guidi, and Maria Taniguchi offers queer feminist takes on Minimalist and Post-Minimalist painting, complementing the plethora of queer figuration on view. (In the latter camp, I was thrilled to see work by Bhupen Khakhar—the first painter in India to frankly address homosexuality—and Salman Toor, a Pakistani American artist living in New York.)

Ana Segovia, Pos’ se acabó este cantar, 2021. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Andrea Avezzù.

Halfway through the Arsenale section, we see a diptych of sorts: in one large gallery, Bouchra Khalili’s The Mapping Journey Project (2008–11), and, in the next, a display entitled “Italians Everywhere.” (This is one of Pedrosa’s three nucleo storico, or historical cores—focused, not-so-small exhibitions within the larger show.) Khalili’s work consists of eight large screens. Off-screen, we hear voices of people describing harrowing journeys from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia to Europe, only to find themselves classified as undocumented, “illegal,” and largely unwanted upon their arrival; we simultaneously watch their disembodied hands tracing their circuitous routes with colored markers on maps. The pieces that make up “Italians Everywhere” were made by artists who left Italy to work abroad, not as “refugees,” for the most part, but as immigrants, expats, colonists, travelers—though others were fleeing fascism, antisemitism, and poverty. Together, these two rooms point to the ways in which modernity was and is marked as much by movement between nations as by the nation-state itself.

Bouchra Khalili, The Mapping Journey Project, 2008–11. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Marco Zorzanello.

Over at the Giardini site, whose façade sports a joyous, colorful mural by the Brazilian MAHKU collective, we encounter what is probably the most controversial aspect of the show: two historical presentations devoted to themes of modernist abstraction and portraiture, respectively. The most common complaint I’ve heard is that presenting cheek by jowl hundreds of works by twentieth-century artists from the Global South—only one per artist—decontextualizes them, reducing them to props in a curatorial argument rather than allowing for a fulsome understanding of individual practices and their connection to their (presumably local) artistic and political milieu. But what might we imagine to be the context for Kazuya Sakai, an artist, designer, critic, and scholar of Japanese descent who taught in Argentina (where he was born), the US, and eventually Mexico, where he became a pioneer of geometric art? Or Sayed Haider Raza, who studied in a Bombay art school, whose ateliers were established by Rudyard Kipling’s father no less, before going to Paris’s École des Beaux-Arts in the 1950s and settling there? Or the CoBrA artist Ernest Mancoba, who was trained at an Anglican missionary school in South Africa, but only found his distinctive sculptural voice after traveling to London, where he was able to study Central African masks? (It was practically the only place he could see these spoils of Great Britain’s colonial pillaging.)

Kazuya Sakai, Pintura No. 9, 1969. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Matteo de Mayda.

In other words: for many artists of the Global South, their context was and is the globe itself. And while a large number have transited through Europe and North America on their artistic journeys, many were just as interested, if not more so, in speaking to other artists who were also emancipating themselves from colonization or reimagining the world after achieving sovereignty. This is the most radical aspect of Pedrosa’s biennale: the refusal to center what we used to call the West. His rejection of art-historical hierarchies like art/craft and insider/outsider/trained/untrained artists, and his choice to avoid, for the most part (and surely relative to the show’s last few iterations), artists represented by blue-chip galleries or too familiar on the art-fair circuit, constitutes a rejection of traditional, Euromerican-driven gatekeeping mechanisms. The Global North is everywhere, no question: in the colonialisms, settler colonialisms, and extractivisms that so many of these artists actively resist; in its seeding of wars; in its building of exclusionary and violent borders, walls, and bureaucracies; in the way it has turned the whole world into grist for capitalism. But while the Global North is present, it does not speak—in Foreigners Everywhere, it’s been put on mute, so we can finally hear the rest of the world instead.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer and critic based in New York. She contributes to the New York Times and 4Columns. Her new book, Imperfect Solidarities, will be published by Floating Opera Press this summer.