Harmony Holiday

Harmony Holiday

A new podcast commemorating the thirty-year anniversary of the musician’s death prompts a closer look at the journals he left behind.

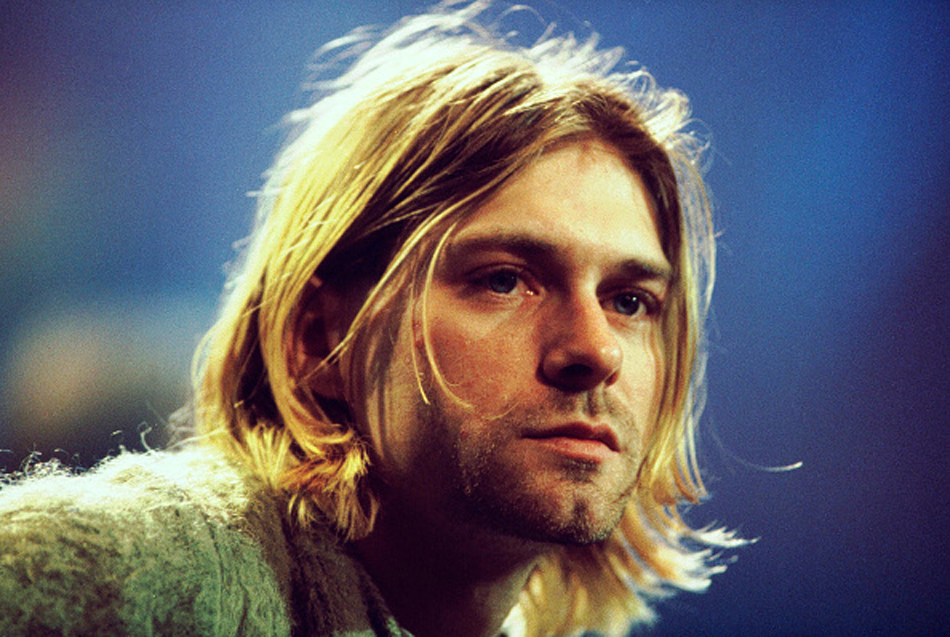

Kurt Cobain during the taping of MTV Unplugged: Nirvana at Sony Studios in New York City, November 1993. Courtesy Getty Images. Photo: Frank Micelotta Archive.

“The Cobain 50,” hosted by Dusty Henry and Martin Douglas, KEXP

• • •

1994 was a year of spectacularized collective grieving: Kurt Cobain died in April; by June, O.J. Simpson was the sole suspect in the double homicide of ex-wife Nicole Brown and her friend Ron Goldman, Bill Clinton was president (soon to be impeached for infidelity), and Cobain screaming “All Apologies” was a strange comfort, inflecting the absurd current of popular culture with self-deprecating beauty. Kurt took his scream and absconded through the portal, or scapegoat, that is the age of twenty-seven for famous musicians. Some call it a club, wherein the ritualistically disfigured glory of golden-children forces them to sing their own dirges to way-too-eager fans who in turn suffocate them with infatuation and envy. We’ve used Kurt for a sunbeam; a prodigal, half-feeble heir whose name insinuates the irritated brevity of overworked receptionists at the gates limning Heaven and Hell, hello, how low—haloed, he didn’t need us; he was hurting, and we couldn’t help him. But, like an escapist with a conscience, he left a survival guide, a record of his fixations, delights, philosophical notions, lyrics, and letters to friends and colleagues, lists of his favorite things, rude-boy disavowals, a smudged collage of the workings of his subconscious, in three-subject Mead spiral notebooks, lined, withered at the corners like the flesh of fingers held underwater too long. He was a Pisces, made an album called In Utero (1993); he was held underwater too long, gasping for the attention that tormented him. His notebooks document his acute self-awareness and loosen our grasp on a man who saw himself and life itself as a hostile, sneering disappointment not worth enduring. He was, as graffitied in his Mead, ashamed to be human.

Toward the end of these notebooks-as-protracted-speech-acts, which reveal Kurt’s subdued zealotry and hunger for direct communication with fans, we receive a list of his top fifty albums, a propaganda leaflet of an intervention. It’s the most circulated document from these revelatory pages. Leadbelly and Public Enemy join Mazzy Star, Aerosmith, the Pixies. The Beatles are there, and R.E.M; no Hendrix, no electric Miles, notable because he didn’t contrive an affinity with peers who shared his afflictions. The list is his long-form autograph on the American Songbook, and the dominant sound it captures is sublimated despair. He would have turned fifty-seven this year, his cynicism further honed by time. KEXP is commemorating Cobain by looking closely at every album he included in a podcast series called “The Cobain 50.” He’d have been as suspicious of the proliferation of podcasts with high-low concepts as I am.

In mapping the intricacies of his musical tastes in typical whisper-in-your-ear podcast style with factoids and deep dives into bands’ founders and sidemen, KEXP does a thorough job, but the tone is too full of wow and wonder, gloss. The hosts, Dusty Henry and Martin Douglas, linger somewhere between starstruck and underwhelmed, though committed to detailed storytelling: we learn why bands exist, how the bassist of the Sex Pistols exited the planet, but not really much about Kurt Cobain’s life in relation to listening to each album. I would love to hear from his friends about how and when he listened to music, how he spoke about it in his private life outside of the soliloquy in his notebooks. As it is, the series feels a little like PR for Kurt’s relatability, a little too lighthearted and audiophile-friendly to be elegy.

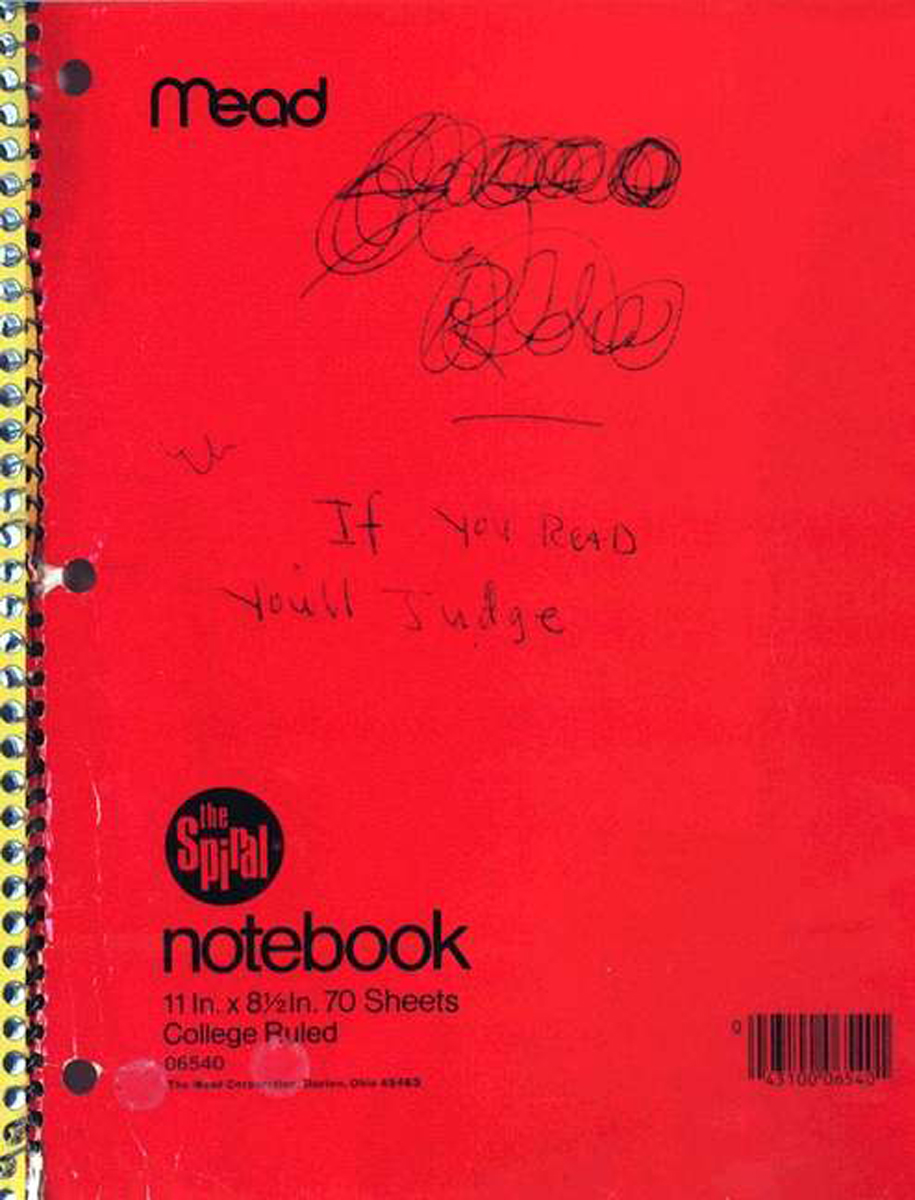

Journals, by Kurt Cobain (Riverhead Books, 2003).

It was searching for this list that afforded me the pleasure and agony of reading Cobain’s monumental journals, without which his listicle is mere agitprop for a composite archetype he idolized in a way he was maybe ashamed to delineate publicly. Shame, especially that of the overachiever, is a wound that can only be dressed occasionally, with willful delusion, the cinched tourniquet through which blood seethes to gush, the rise of opiates in his bloodstream abating the chronic abdominal pain from which Cobain suffered. He shouts in ballpoint, I am not a junkie, disavowing the cult of Burroughs a little, and goes on to describe in detail his erratic intestinal spasms, which doctors failed to treat or diagnose. He self-medicated so he could function. All these decades later, with the US in the mire of a reinvigorated opiate crisis, scientists have begun calling the gut microbiome a second brain. There is research suggesting that depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia can be triggered or exacerbated by what they call “leaky gut,” or micro-tears in the intestinal lining that allow toxins from our compromised food supply (lethal chemicals like Roundup™ and atrazine) to reenter the bloodstream instead of being digested and eliminated as waste. This is not the glamorously nostalgic, elegiac mode befitting the anniversary of the tragic death of a cultural hero, but in reading and rereading Cobain’s notebooks, the man I encounter is one who divided time between reverie—total commitment to his craft to a neurotic, sublime extent—and violent physical pain. He gave us the soundtrack to pain’s tantrum as it softens into numbness, and sometimes lullaby and sometimes nightmare.

In a meandering treatise on guilt in one of the journals, he calls himself “disclaimer-boy” for abandoning his former “comrades.” He was from a working-class family in Aberdeen, Washington, just outside of the Seattle he helped make famous for liberal sadness. A few entries later, he describes a heroin binge after Nirvana’s European tour: “got a little habit, kicked it in a hotel in 3 days.” He tells us and his memory he was given methadone to wean, that he suffered terrible gas, had to be hospitalized—all of this confessed beneath his litany of mocking, imagined interrogations from the press. “Are you gay? Are you the dead Elvis or the living one?” He loops his testimonies to himself as if on trial. He explains his first time trying heroin in 1987, and that he used ten times between then and 1990. That was the year he began experiencing excruciating pain whenever he ate almost anything. This page—stained, as if by tears or stigmata—unlined. He intervenes on the witness stand of his mind to sketch impressive diagrams of guitars. He loves Leadbelly who makes it on his drunken boat. They traipse through cemeteries together on a tightrope hunting for hooks. These are pain diaries, intricate and generous in their understanding of how the body’s misgivings tax the spirit or hijack it with sheer blue intensity, the hue of Kurt’s own shoring eyes. Drug use is escapism whether you want to admit it or not, he resolves, in a penultimate entry; he predicts explicitly that it will take fifteen to twenty-five years for anyone with a wounded ego to really kick. He admits he’s proud of having met Burroughs, that he’s earned five million in the past year—And I’m not gonna donate a single dollar to the needy indie-fascist regime, they can starve. Let them eat vinyl.

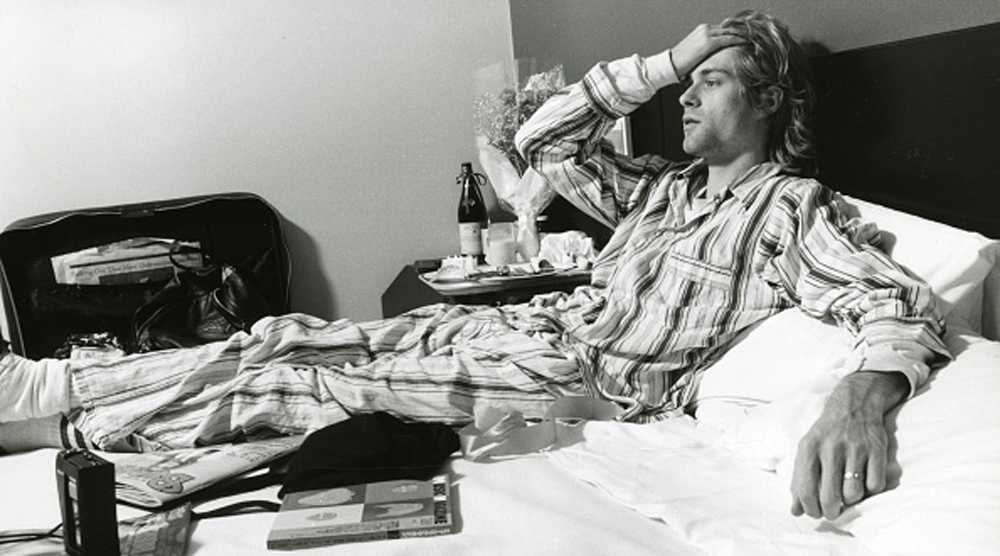

Kurt Cobain in Roppongi Prince Hotel in Tokyo, December 1992. Courtesy Getty Images. Photo: Gutchie Kojima / Shinko Music.

Ashamed of his pain, ashamed of his sweetness and capacity for beauty, of his tolerance and lack thereof, of his aloof petulance, of his good taste, of his anhedonia, his hedonism, his success, of how popularity accentuated his loneliness, and, finally, ashamed of the ambition and love of music that alleviated the ache but also helped him become the conduit through which suburbanites gentrified a working-class sensibility in sound—Kurt’s conversations with himself get so bleak they become one long transcendent warning to those who would construe his helplessness as courage, his suffering as carelessness. The list of albums is the only interlude in Kurt Cobain’s journals that isn’t inflected with ignominy or blunt humility, just titles and band names in a gnawing hierarchical arrangement that distracts him from the sharp pangs of being himself for one slender entry.

Turning the page, we meet a Sharpie drawing of a male seahorse accompanied by a caption about its childbearing abilities. Scarecrow, harbinger of phantoms. He then credits his daughter Frances for shifting his attentions from worry about domestic terrorism and right-wing politics to rebirth. Then he’s gone. There is no cure for being a prodigy. Pain made coherent as song is the closest he came to escaping alive.

Harmony Holiday is the author of several collections of poetry and numerous essays on music and culture. Her collection Maafa came out in April 2022.