Jorge Carrión

Jorge Carrión

Two shows on view at Hauser & Wirth Menorca connect to architectural space and landscape—and each other—in surprising ways.

Roni Horn, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Stefan Altenburger. © Roni Horn.

Eduardo Chillida: Chillida in Menorca and Roni Horn, Hauser & Wirth, Illa del Rei, Menorca, through October 27, 2024

• • •

Art traffics in the poetic metamorphosis of materials. The Basque sculptor Eduardo Chillida (1924–2002) and the New York–based artist Roni Horn, whose works are now on display at Hauser & Wirth’s gallery on Menorca’s tiny Illa del Rei, are masters of that kind of process. The context of the exhibitions, on an island in the Mediterranean, sheds unexpected light on these two creators, establishing a link between artists that few would think to connect.

Eduardo Chillida: Chillida in Menorca, installation view. Courtesy the Estate of Eduardo Chillida and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Damian Griffiths. © Zabalaga Leku.

Eduardo Chillida came to prominence in the mid-twentieth-century with imposing works in stone and metal, which—in the wake of Pablo Picasso and Henry Moore—associate abstract, mostly biomorphic forms and references to the cryptic remains of prehistoric monuments and traditional dwellings found in the Basque Country. He is best known for the large-scale public projects that he executed at the end of his career, when he started spending his summers in Menorca and investigating its cultural heritage. Featuring more than sixty works, Chillida in Menorca foregrounds pieces that were made here, although it also includes earlier examples.

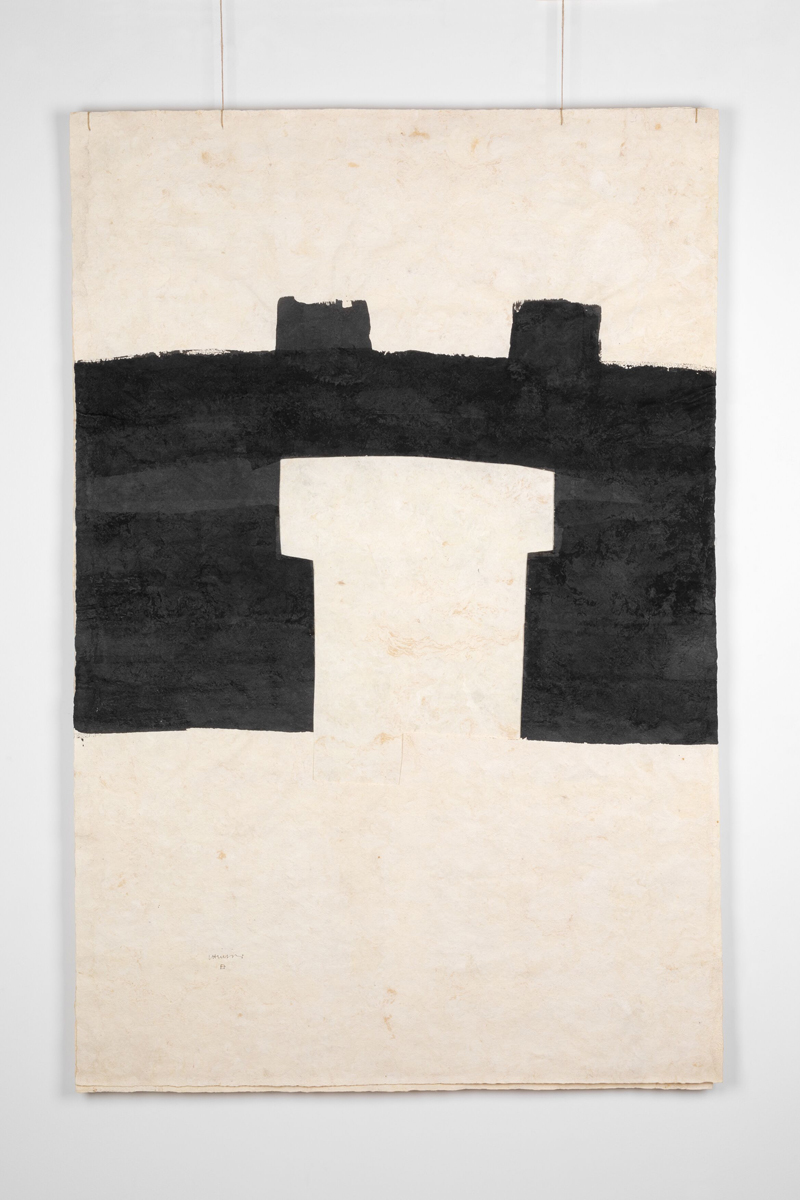

Eduardo Chillida, Gravitación (Gravitation), 1990. Paper, ink, and string. Courtesy the Estate of Eduardo Chillida and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Abril. © Zabalaga Leku.

Some of the self-standing sculptures are labyrinthine structures of positive and negative space, orifices and protuberances, that act like devices to capture, process, and redirect the limpid light, while also possessing an at once earthy and ethereal character. For several works on paper, Chillida superposed materials with different textures. They have a rough, heavy, almost sculptural character. Others are of a more traditional, “drawerly” nature, like the eight studies of how to draw a hand (1965–87); these images stand out for their simplicity. They are reminiscent of a storyboard sketch for an animation, with the fingers moving to catch something that is not visible, with the natural tools that connect project and material, idea and execution.

Eduardo Chillida: Chillida in Menorca, installation view. Courtesy the Estate of Eduardo Chillida and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Damian Griffiths. © Zabalaga Leku. Pictured, foreground: Homenaje a la mar IV (Homage to the Sea IV), 1998. Background, outside: Saludo a los pájaros II (Salute to the Birds II), 2000.

From his childhood by the Atlantic, Chillida remembered his insistent contemplation of the waves. He even said the sea was his teacher. That is perhaps why the most emblematic contrast in his exhibition is between the two largest sculptures. One stands inside the North Gallery and the other outside, connected by the transparency of a large window. Homage to the Sea IV (1998) reproduces in alabaster the rugged coast of the Cantabrian Sea on a rough stone base. Then, in the open air and among trees, we see Salute to the Birds II (2000), a sculpture that seems almost weightless, soaring.

Roni Horn, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Stefan Altenburger. © Roni Horn. Pictured, left foreground: Untitled (“A witch is more lovely than thought in the mountain rain.”), 2018 (detail). Far right: Key and Cue, No. 1443, (A CHILLY PEACE INFESTS THE GRASS), 1994/2000.

The gesture of catching and releasing is also pervasive in Horn’s exhibition, which consists of four projects displayed in two spaces. The main room houses the nine large, circular sculptures that comprise Untitled (“A witch is more lovely than thought in the mountain rain.”) (2018). These disks, placed in an irregular formation on the floor, are made with solid cast glass but seem liquid, unstable, like puddles encapsulated in color, or amber that could break at any time. They are counterpointed by four pieces from the Key and Cue series, which transform the first lines of Emily Dickinson’s poems into vertical sculptures, shiny sticks with cryptic fragments of text propped directly on the wall, forcing us to change the usual sense of reading, breaking the textual whole they supposedly integrate, while giving them a new, three-dimensional nature.

Roni Horn, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Stefan Altenburger. © Roni Horn. Pictured: Double Mobius, v. 2, 2009/2018.

From these sets of multiple parts, in the hallway we switch to single pieces. Double Mobius, v. 2 (2009/2018) is made of two distinct ribbons of pure gold that are joined at an indistinct point. They intertwine and crumple and come together; the object is both a golden rag and a jewel (this ambivalence between the discarded and the precious is frequent, too, in Chillida’s work). And, in the side room, Black Asphere (1988/2006) is a solid copper sculpture that, from a distance, looks like a ball or a sphere, but up close reveals itself to be an “asphere,” that is, asymmetrical on one axis. Horn has described it as a self-portrait. The work eludes binarism; even while it urges the viewer to identify the nature of the object in front of them, it defeats every such attempt to accomplish that task, refusing to define itself.

Roni Horn, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Stefan Altenburger. © Roni Horn. Pictured: Black Asphere, 1988/2006.

Both Chillida and Horn are associated with the Atlantic: the Spanish artist spent his life consciously exploring the light, the waters, the landscapes of the Cantabrian Sea and the ocean that surrounds it; the New York artist has worked on the meteorology of Iceland and the waters of the Thames. Perhaps this is why I was surprised by the effect that the Mediterranean Sea had on their work. In the current exhibitions in Menorca, both are set in dialogue with the architecture and the light of the space, which become creative agents, a third vertex in the triangle of experience.

Eduardo Chillida: Chillida in Menorca, installation view. Courtesy the Estate of Eduardo Chillida and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Damian Griffiths. © Zabalaga Leku.

Large windows let in streams of light and turn the turquoise blue of the sea transparent. It is impossible to separate one view from the other: the shimmering light refracted on the water adds a trembling quality to these objects, which exist in an indeterminate state, seemingly engaged in a process of constant transformation. The tension of the context seems an amplified echo of the tensions that we find in each work. Whether the transformation of materials is truly poetic depends as much on the artist as on their reader. And light always determines our readings.

Jorge Carrión has a PhD in Humanities from the Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona, and manages the Master’s in Creative Writing program at the same institution. He is the author of a tetralogy of fiction, Las huellas (Los muertos, Los huérfanos, Los turistas, and Los difuntos) and is also the author of various nonfiction books, such as Australia: Un viaje, Teleshakespeare, Librerías, Contra Amazon, Madrid, and Libro de libros (published in English as Bookshops, Against Amazon, Madrid, and Book of Books). His work has been translated into fifteen languages.