Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

Riotous shows, near-fatal fights, and anti-racism and protest politics: a new book chronicles the influential era of the Specials and 2 Tone Records.

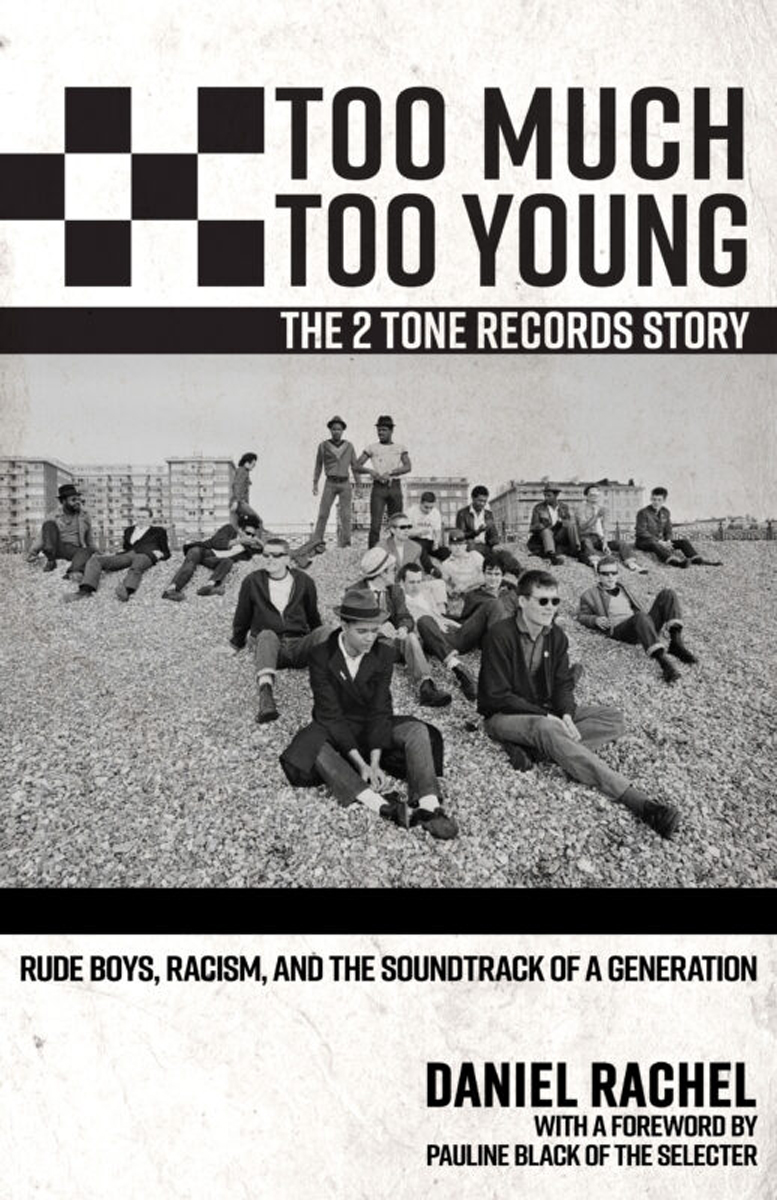

Too Much Too Young: The 2 Tone Records Story, by Daniel Rachel, Akashic Books, 485 pages, $32.95

• • •

There are memories that, even when false, carry us toward something, or rather pin us to a feeling we keep trying to understand, no matter how strenuously it resists parsing. One of mine is seeing the Specials in August 1981 at the Ritz, now restored to its original name, Webster Hall. Since that day, I have carried with me an impression that life would be somehow incomplete if I were not in a band. What returns me to this is a mental loop: under blue light and using comically long strides, keyboard player Jerry Dammers lopes back and forth across a stage, like someone imprisoned in an aquarium full of sweet nitrogen. The band was performing “Ghost Town,” which is described in Daniel Rachel’s new Too Much Too Young: The 2 Tone Records Story as “one of the greatest and most widely acclaimed songs in UK pop history.”

I think today what I thought in 1981, which is that God had simply reached out and asked the Specials to give voice to everyone in England—suffering 10 percent unemployment or, in the Specials’ hometown of Coventry, 20 percent—and created a memory for all with as productive a grain as mine. The sound of eternal frustration, of skeletons who wish they could play the piano (like those on the cover of the twelve-inch, which I stared at for hours) is in “Ghost Town,” a recording that introduced concepts that remain as unresolved as they are crucial. The music is dub, easy listening, reggae, half-dead rock, all of it basted with some kind of invented memory of the Arab diaspora. The music is both completely melodramatic and emotionally accurate. If you can’t find a job, you’re going to turn into a freaky skeleton musician with six friends!

Only two years before this show, Dammers founded 2 Tone Records with the idea that the label would be “self-sufficient, all-encompassing and racially integrated,” as he once described it to Suggs of Madness, another 2 Tone band. The label remained in operation until 1986, during which time it put out thirteen albums and fifty singles, some of them still unmatched in devious synthetic power. Rachel’s book is nearly five hundred pages of shows and fights and long, long quotes from all the major players here. But the fights—staged, real, epic, near-fatal, racially motivated, alcoholically induced, contained by buses, contained by hotel rooms, and one that landed Specials singer Terry Hall and Dammers in court for provoking Cambridge football hooligans. Dammers, upon being fined, announced to reporters, “This ain’t a town. It’s a trained-dog act! That’s a quote from an old film by the way.”

It is Dammers who makes most of this happen, and Coventry was his seat. Bombed out in WWII, and then an auto-making hub in the ’50s and ’60s, Coventry had the right mix of unemployed youth, Windrush kids, and cheap gear to provide the soil. Dammers, the son of politically minded folks, wanted not only to create a hybrid version of ska unlike anything else (check) but to launch an independent label that could help other struggling bands (check) and change attitudes around race and class in popular music (insofar as that can be done, check). If you know about ska music, it is likely because of the revival that Dammers and the Specials kicked off. Even the people in the band who clashed with him, especially guitarist Roddy Byers, allow that his vision is what made the Specials work. Some of the spark came from punk music, somewhat deflated by 1979, but an inspiration in terms of what Dammers later characterized as “protest music.” Punk did little to recast how race was seen, even in small independent bands, but a music based on Jamaican ska, played by a band of both Black and white musicians, might do the trick.

Dammers cobbled together a gang of locals playing in soul, rock, or reggae bands, none of them yet playing strictly ska. Not that the Specials ever played pure ska, not really. Their first single was based on experiences dealing with the unsavory characters who financed clubs and record labels—“Gangsters,” a frantic and unsettling tune that never entirely made sense to me. The first line, sung by Hall as if forced at gunpoint to become a singer, is “Why must you record my phone calls? Are you planning a bootleg LP?” “I never understood the lyrics, although I wrote them,” Rachel quotes Dammers. The organ line Dammers plays is, though Rachel does not note this, an obligato melody that is not so different from what shows up in “Ghost Town” two years later (call it cod Arabic). The flip side of the single is called “The Selecter,” performed by a band that ended up having the same name as the song, an old demo recorded by songwriter Neol Davies, drummer John Bradbury, and Bradbury’s brother-in-law, Barry Jones, on trombone solo. The Selecter developed into a rugged, legitimate band with one of the most ice-cold stylish singers in the history of pop, Pauline Black. Through the years, the core of 2 Tone was made up of these two bands, though others, like Madness and the Beat, ended up having long lives on the charts after leaving the label.

2 Tone was essentially distributed and operated by Chrysalis, leaving its fourteen-member collective to make decisions to which no band was contractually obligated, ever. Dammers made all the decisions, in reality, as he did for the Specials. He was especially adept at terrorizing art departments and demanding that flyers and posters and album covers be de-fancified and roughed up, closer in spirit to their Jamaican inspirations. Dammers was tapping into something much bigger than him and his friends—“Gangsters” was the biggest-selling independent single of 1979, and Elvis Costello declared it “one of the best records of the last ten years” on BBC’s Roundtable radio show. He ended up producing the band’s debut album, saying, “I thought it was my job to learn everything I could about the band before some more technically capable producer fucked it all up and took the fun and danger out of it.”

Look up videos of the Specials or the Selecter and you will see confirmation of the hyperbolic accounts contained in Rachel’s book, of live shows never since bettered. (If the Selecter did not have songs as good as the Specials, their show seemed as divinely energized.) What haunts about this transitional moment is that, only a few years before rap would fully transform popular music so that the past would become partly erased in the wake of sampling’s constant reframing, a bunch of English kids had to figure out a new music with their hands and feet. The ska revival that has stretched out since 1979, healthy across many countries, is likely more faithful to Jamaican records of the ’60s than anything the Specials did. Their blend was heavily indebted to punk energy and had the tone and coloring of American soul, as well as a heavy dose of what Dammers called “muzak.” The band’s magnificent second LP, More Specials (1980), was indebted to Dammers absorbing “Mantovani, John Barry and all things Muzak,” per Byers. That vortex is where “Ghost Town” was born.

By the time I saw the Specials, Terry Hall, Lynval Golding, and Neville Staple had quit the band and been coaxed back. Rachel does a very good job at capturing how much happened in two and a half years, and what happened after the Specials proper ended. Two of the most vital Specials songs were released by the post-Hall version of the band, renamed the Special AKA: a brilliant recitatif about sexual assault containing almost a full minute of screaming, Rhoda Dakar’s “The Boiler,” was released in 1982, and “Free Nelson Mandela” (still a presence on the radio today) was released in 1984. Much of the spirit of 2 Tone ended up in Bristol acts like Massive Attack and Tricky, the latter of whom tapped Hall for several songs on his Nearly God album in 1996. There will be another emergence, soon, of these beautiful skeletons, none of them ever fully asleep.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York. His memoir, Earlier, was recently published by Semiotext(e).