Michelle Orange

Michelle Orange

A loving mother-daughter bond fumbles tenderly toward rupture in

Annie Baker’s debut feature.

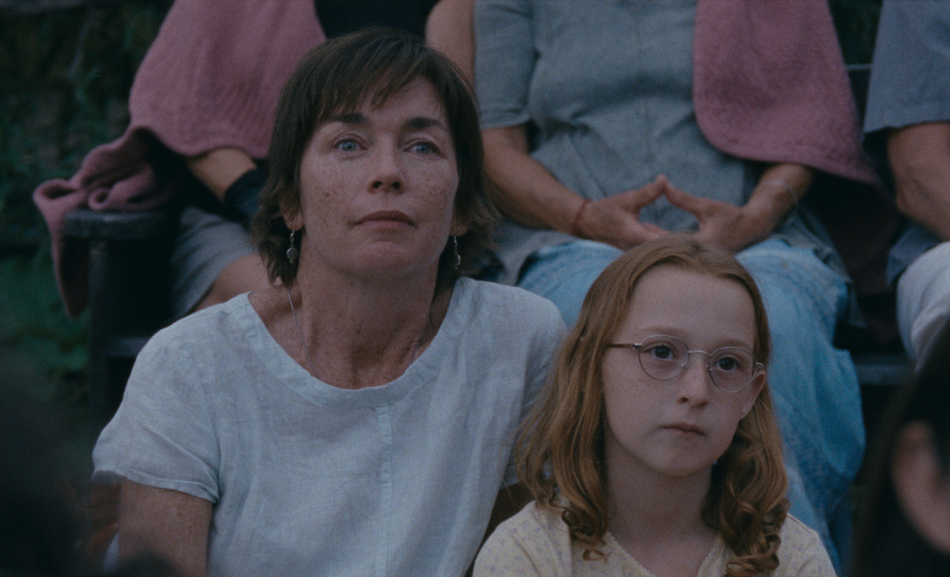

Julianne Nicholson as Janet and Zoe Ziegler as Lacy in Janet Planet. Courtesy A24.

Janet Planet, written and directed by Annie Baker, now playing in New York City theaters, opens nationwide June 28, 2024

• • •

The heart of a child is a gerrymandered thing: bound—rigged, you might say—to fix itself upon the nearest viable adult. In time, together with the advance of a discernment beyond the heart’s domain, such affinities enter their first season of review. Settled boundaries kink and grow porous; a ruling passion begins to color and distend. Outcomes vary, of course, but even the quietest, most loving rupture between child and parent is a rupture all the same.

Quiet, if not silence, surrounds eleven-year-old Lacy (Zoe Ziegler), the owlish presence at the center of Janet Planet, the playwright Annie Baker’s feature-film debut. We meet Lacy in her pre–middle school interregnum: the summer of standing with crossed arms and a crook in one leg; of haunting the Western Massachusetts property, blanketed in birdsong and insect noise, where she lives; and of an incipient, almost invisible slippage in her attachment to her mother, Janet (Julianne Nicholson), who runs an acupuncture and wellness practice (“Janet Planet”) in a studio alongside their woodsy, wood-beamed home.

Julianne Nicholson as Janet and Zoe Ziegler as Lacy in Janet Planet. Courtesy A24.

It is 1991. Janet and the women in her contra-dancing, theater-collective-adjacent, neo-hippieish milieu wear long skirts with buttons up the front and flowy tops with buttons down the back. Our view of Janet—a warm but dazed, abstracted figure—derives almost exclusively from either Lacy’s point of view or a cinematic equivalent of the close third person, where the fixed quality of the daughter’s attention to her mother dominates their shared scenes. The one sequence in which Lacy is not present opens with Janet remarking on her daughter’s inescapable gaze, of feeling her eyes on her even when they are apart.

Julianne Nicholson as Janet and Zoe Ziegler as Lacy in Janet Planet. Courtesy A24.

That moment, late in Janet Planet, also marks the first time we see Janet speak in the presence of either of the two men who pass through her life that summer. The ruler of Lacy’s world, Janet appears to be something of a bystander in her own. With the grizzled, opaque Wayne (Will Patton), whose continued installment in their home Lacy protests after her dramatic plea to leave sleepaway camp (“If you don’t come get me, I’m going to kill myself,” she threatens, via late-night collect call, in the movie’s opening), Janet is passive to the point of disinterest, their pairing a function of some private, mysterious drive. “You want me to tell you what to do?” Lacy asks her mother, who has sought her advice after Wayne—who disapproves of mother-daughter co-sleeping, but whose own daughter, Sequoia (Edie Moon Kearns), offers Lacy an elusive dose of tween girl kinship—behaves badly. The answer is clear: Wayne must go. Only Lacy seems uncomfortable with the question.

Zoe Ziegler as Lacy and Julianne Nicholson as Janet in Janet Planet. Courtesy A24.

Baker’s patient, tender eye for detail and dry, observational style combine to render with uncommon nuance the study of a bond funneling toward its own disruption. Janet no longer wishes to sleep holding hands, or with Lacy’s palm cupped to her cheek. Lacy would prefer not to watch her mom tripping balls and waxing epiphanic with the resurfaced friend, Regina (Sophie Okonedo), who moves in to escape a toxic relationship shortly after Wayne moves out. Neither mother nor daughter communicates these things directly, though Lacy privately agrees with what Regina calls Janet’s “terrible taste in men.” Something must change, though not because Janet is a “bad” mother, or Lacy an abnormal child.

Sophie Okonedo as Regina and Julianne Nicholson as Janet in Janet Planet. Courtesy A24.

Moments that might otherwise invite such judgment yield and soften within Baker’s broad, static frames (Maria von Hausswolff served as cinematographer, shooting on 16 mm). Long, naturally lit portrait shots and prolonged silences foment a highly controlled emotional landscape, one prone to melancholy and the occasional arid gust of humor. Against this backdrop, the predicaments of both mother and daughter are set into an accretive, slow-growing relief: Lacy is isolated in part by her own lonely, mom-centric design; Janet’s reliance on her power to attract men has hollowed out her life. Baker is interested in the questions that gird both reckonings: What bonds exist beyond the realm of boundless, unchosen love? Is it possible to attach freely—or free, at least, from self-betrayal?

Zoe Ziegler as Lacy in Janet Planet. Courtesy A24.

In a 2013 profile, Baker described growing up with parents who each married multiple times: “There were a lot of people coming in and out of my life . . . I found that very destabilizing and, as a child, very infuriating.” Something of that fury survives in Lacy, whose look of wizened appraisal belies the child who still puts a misfit troupe of figurines to bed each night (Baker cast the solemn, magnetic Ziegler, a nonprofessional, just days before shooting was set to begin). “You know what’s funny?” she tells her mom in bed one night. “Every moment of my life is hell.” Along with Baker’s fondness for a pithy title card, the line recalls Wes Anderson’s world of droll and mordant kids. But in its willingness to linger, to foreground character as a function of existence in time, Baker’s film is more closely allied with the work of Chantal Akerman: scenes of gloom and stillness offset by streaks of life.

Zoe Ziegler as Lacy in Janet Planet. Courtesy A24.

Toward the end of Janet Planet, Janet’s newest lover, Avi (Elias Koteas, perfection as a small-time, small-town art monster), reads to her from the fourth of Rilke’s “Duino Elegies” during an evening picnic. Lacy, home alone and faking illness to avoid her first days of sixth grade, microwaves a blintz—sans fruit—for dinner. Janet appears lost in the speaker’s address to the parents “who loved me / for that small beginning of my love for you / from which I always shyly turned away,” and the sequence ends with a ping of surprise, a pattern disrupted. The power of what follows derives in part from our sense of this disruption as no less meaningful than Janet’s return to form. Lacy recognizes a little ahead of schedule what we all must face eventually: her mother is who she is. Throughout Janet Planet, but especially in its stirring final moments, we inhabit with her the void separating the heartache of that knowledge from the grace of its acceptance, hidden but still burning in some far-off sky.

Michelle Orange is the author, most recently, of Pure Flame: A Legacy.