Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

A Whitney Museum show examines the impact of Mexican muralists

on US art.

Diego Rivera, Flower Festival: Feast of Santa Anita, 1931. Encaustic on canvas, 78 1/2 × 64 inches. © 2020 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust / Artists Rights Society. Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource.

Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925–1945, curated by Barbara Haskell with Marcela Guerrero, Sarah Humphreville, and Alana Hernandez, Whitney Museum of American Art,

99 Gansevoort Street, New York City, through May 17, 2020

• • •

Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925–1945 is a sprawling exhibition, comprising almost two hundred objects and taking over almost the entire fifth floor of the Whitney Museum. Its art historical ambition equals the square footage devoted to it. Curated by a team led by Barbara Haskell, Vida Americana aims to reorient our view of art in the US, demonstrating that in the period in question—a moment marked by the Great Depression, the Spanish Civil War, World War II, and the cultural and historical reverberations triggered by these events—artists who were searching for ways to confront the growing urgencies of their time were much more apt to look to Mexico, with its formally and politically radical activist artists, than they were to embrace the cool intellectualism of European modernists.

José Clemente Orozco, Barricade (Barricada), 1931. Oil on canvas, 55 × 45 inches. © 2019 Artists Rights Society / SOMAAP. Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource.

Given the current demonization of those who live just south of the US border—as criminals, as “illegal” immigrants, as desperately and unforgivably poor (ideas that have been promoted in Trump’s MAGA rhetoric, but which have long preceded him)—the reminder that Mexico was once regarded by people in the US as a cultural center worth emulating is a welcome one. In the wake of the Mexican Revolution, a decade-long civil war that ended around 1920, the new Mexican government initiated a public art program. The muralists who took part—especially Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco—were celebrated for their achievements both at home and abroad, admired for their ability to fuse inventive style and technique with a commitment to social justice. Their fame led to invitations from US private entities, local governments, and FDR’s New Deal–era Works Progress Administration (WPA) to undertake important commissions here. In the process, they trained a generation of painters who found work as their assistants.

Alfredo Ramos Martínez, Calla Lily Vendor (Vendedora de Alcatraces), 1929. Oil on canvas, 45 13/16 × 36 inches. © The Alfredo Ramos Martínez Research Project, reproduced by permission.

Vida Americana is divided into nine sections. The first, “Romantic Nationalism and the Mexican Revolution,” offers a view into the state of Mexican art at the time. Artists such as Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Alfredo Ramos Martínez, and Rufino Tamayo developed a visual language that drew on Indigenous imagery and mythology, stretching from the Aztec and Mayan empires to the very contemporary resistance of rural peasants and farmers under the banner of agrarian leader Emiliano Zapata. Martínez’s Calla Lily Vendor (1929) and Rivera’s Flower Festival: Feast of Santa Anita (1931) both depict peasant women as pure innocence, surrounded by blossoms even as they are burdened by work; they share, too, strictly symmetrical compositions, a nod to Mayan compositional strategies. This section also incorporates painting, photography, and film by foreign artists (US-, Canada-, and even, in the case of Sergei Eisenstein, Soviet Union–based) who doubled down on this romanticized notion of cultural authenticity, often as a result of their work and travels in postrevolutionary Mexico.

Diego Rivera, Man, Controller of the Universe, 1934. Fresco, 15 feet 9 inches × 37 feet 6 inches. Palacio de Bellas Artes, INBAL, Mexico City. © 2020 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust / Artists Rights Society. Reproduction authorized by El Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura, 2020.

Four sections of the show—“Orozco on the Coasts,” “Siqueiros in Los Angeles,” “Rivera and the New Deal,” and “Rivera and Rockefeller Center”—revolve around these artists’ major mural projects in the US. Each of these large-scale undertakings has been represented in the galleries by proxy: Orozco’s Prometheus (1930), done for the dining hall of Pomona College, is shown via a color reproduction pasted into a half-scale model of the arched nook for which it was executed. Siqueiros’s Tropical America (1932), one of the three murals he created during a stay in LA, influenced by techniques he gleaned from the film industry there, is represented by a blown-up photograph taken just after it was completed, since the original was whitewashed. (It is now under conservation at the Getty.) Rivera’s epic Detroit Industry (1932–33), gloriously in situ at the Detroit Institute of the Arts, appears as a panoramic projection on the walls of one gallery, accompanied by touch screens where visitors can home in on details as they wish. Rivera’s infamous Man, Controller of the Universe (1934) was commissioned by the capitalist fat cat Nelson Rockefeller—who immediately covered it and eventually destroyed it when Rivera, a committed Marxist, added Lenin to the crowds of people surveying the fruits of industry. In his rage, Rivera made a replica for the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City; a full-scale, color reproduction of the work is on view at the Whitney.

Eitarō Ishigaki, The Bonus March, 1932. Oil on canvas, 56 7/8 × 41 11/16 inches. Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama, Japan.

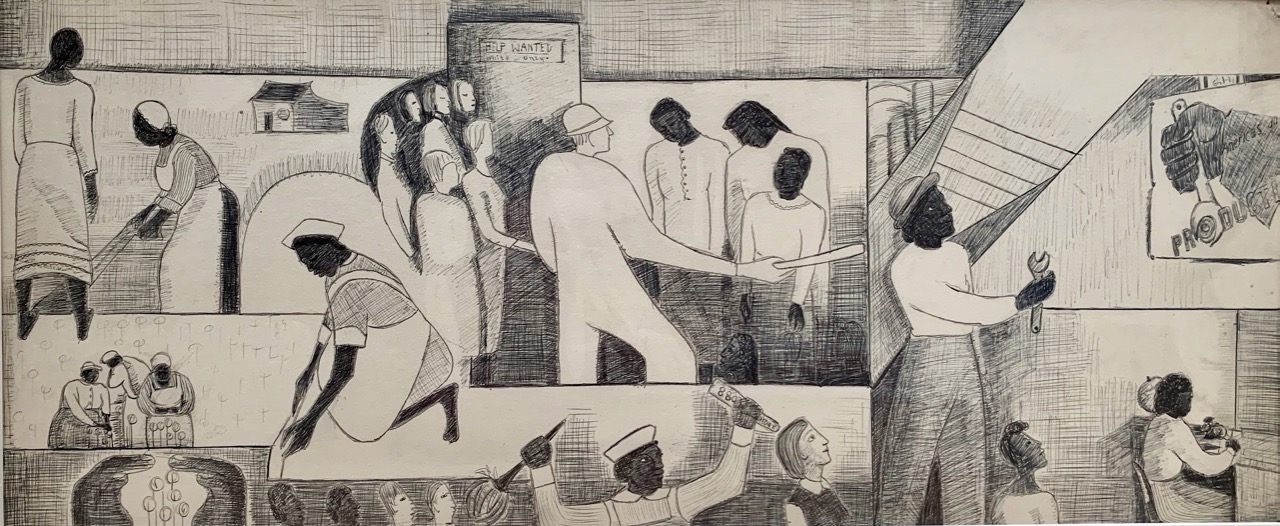

These epic projects are surrounded by the creations of artists who studied, worked with, or were inspired by the Mexican muralists. Some are household names; Jackson Pollock, for example, was especially influenced by Siqueiros’s formal inventiveness, and took part in the Mexican artist’s experimental workshops in New York in the 1930s, where he got turned on to the idea of chance operations and alternative modes of mark making. Others, like the Japanese American painters Eitarō Ishigaki and Hideo Benjamin Noda, are less well known. Because of their leftist, anti-colonialist politics and a sense of racial solidarity, the muralists embraced Black and other artists of color in the US, bypassing the usual segregations of the art world; as a result, this revisionist exhibition offers the opportunity to see that figures such as Charles White, Jacob Lawrence, Aaron Douglas, Hale Woodruff, and Elizabeth Catlett were at the very center of advanced artistic culture in this period, not on the margins, where they’ve been relegated by mainstream art history until recently. One of Rivera’s favorite artist assistants, an audio guide tells us, was a Black woman, Thelma Johnson Streat, whose The Negro in Professional Life—Mural Study Featuring Women in the Workplace (1944) deploys a graphic style to portray the entry of Black women laborers into factories during World War II, and the discrimination they continued to face there.

Thelma Johnson Streat, The Negro in Professional Life—Mural Study Featuring Women in the Workplace, 1944. Ink and graphite on paper, 12 1/2 × 30 inches. Image courtesy Bernard Friedman collection.

Whitney Museum director Adam Weinberg, in his foreword to the show’s impressive scholarly catalog, speaks both to the question of why a museum devoted to US art would direct resources toward showing Mexican artists, and, simultaneously, why it took so long to do it. (Haskell, he notes, has been trying to realize this exhibition for nearly a decade.) His answer is, roughly, that there is something in the air—the Whitney is one of a number of museums that are finally turning their attention to the rest of the Americas in their quest to diversify the stories they tell, especially in light of our current anti-immigrant political policies.

But this overlooks the crucial role Latinx artists have been playing in pushing museums to address their historical blind spots. In 2016, Teresita Fernández convened a daylong symposium at the Ford Foundation to address “US Latinx Art Futures.” Artists, curators, and museum directors (including Weinberg and his chief curator, Scott Rothkopf) were invited to discuss the increasingly glaring oversight of the work of US-based Latinx artists and lack of attention to Latinx audiences. Compounding the problem, she noted, is that museums are apt to believe they are doing their duty by showing the art of Brazilian, Argentine, and other foreign artists, while failing to show works by US artists who trace their roots to Central and South America. From an Instagram post at the opening of Vida Americana, in which Rothkopf thanks Ford Foundation head Darren Walker and Fernández—“you showed me the way,” he writes—one might reasonably assume that the symposium had its intended curative effect. But if there is growth, there is also irony to this extraordinary and art historically important show: despite the fact that hundreds of US Latinx artists were actively involved in WPA projects across the United States, and were, like their non-Hispanic counterparts, influenced by the Mexican muralists, not a single work by a US Latinx artist is on view.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. She is co-curator of Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And, an upcoming retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum of Art; editor of Lorraine O’Grady: Writing in Space, 1973–2019 (Duke University Press, 2020); and a member of the advisory board of 4Columns. In 2020, she received a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant for short-form writing.