Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

From docufiction to Eartha Kitt’s upheavaling day: a MoMA film series.

Osceola Archer as Mrs. Cluny and Diana Sands as Janice in Love as Disorder, 1973, directed by Ben Maddow. Image courtesy Everett Collection.

“It’s All in Me: Black Heroines,” organized by Steve Macfarlane, Dara Ojugbele, and Marta Zeamanuel, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through March 5, 2020

• • •

The winter repertory-film season in New York has been devoted to saluting performers too often under recognized, in movies about lives still too rarely depicted onscreen. Last week, Film Forum concluded its monthlong “Black Women: Trailblazing African American Actresses & Images, 1920–2001,” which primarily showcased studio releases. (Though not exclusively: I was thrilled to be one of at least two dozen spectators for an afternoon screening on a dreary late-January Tuesday for Bush Mama, Haile Gerima’s fiery, funny, disjunctive UCLA thesis film from 1979 and a key title of the LA Rebellion movement.) Now underway at BAM is “Happy Birthday, Toni! A Celebration of Black Women,” an eight-day series of shorts and features occasioned by what would have been Toni Morrison’s eighty-ninth year around the sun. Arguably the widest-ranging of these tributes, though, is MoMA’s “It’s All in Me: Black Heroines,” its title repurposing a lyric from “I’m Every Woman,” the perennial dance-floor banger (whether Chaka Khan’s 1978 original or Whitney Houston’s 1993 cover). Spanning 1907 to 2018 and culled exclusively from the museum’s collection, “It’s All in Me” boasts several deep cuts: three of the four films I discuss in detail below were works that I had not only never seen before but hadn’t even known existed.

One of these rarities is Ben Maddow’s Love as Disorder (1973), a reedited version of An Affair of the Skin, a quasi-Cassavetian drama tracking the romantic entanglements of New York City depressives that he had released a decade earlier. In his revision, Maddow wisely placed more emphasis on Janice, an acerbic photographer and the lone central character of color. She’s played by the great Diana Sands, best known for her portrayal of the tradition-flouting Beneatha Younger in the original 1959 Broadway production of A Raisin in the Sun, a role she reprised in the 1961 screen adaptation.

Although Janice flirts with the miserably married Allen (Kevin McCarthy)—her “sweet honky acquaintance,” per her barbed voice-over commentary, which Maddow added for Love as Disorder—she largely stands aloof from the bed-hopping and betrayals of a quartet of white creative classers. She also seems to be the only one in the film who actually does any work: Love as Disorder opens and closes with sequences of Janice snapping shots of Gotham street life; at home in her two-story loft, she’s often busy in her darkroom. Hilton Als once wrote of the Actors Studio–trained Sands, who died of cancer at the age of thirty-nine in 1973, that “she was always alive . . . Not just alive to the scene or character or camera she was playing to, but available to the alchemy that was happening right before you as you watched her watching.” That description is repeatedly borne out in Maddow’s movie, in which she is always a piquant observer.

Lillian Folley in Lillian, 1993, directed by David D. Williams. Image courtesy the artist.

Ever vigilant, too, is Lillian Folley, the protagonist of David D. Williams’s warm docufiction Lillian (1993). Consisting mainly of staged scenes in which several of the “characters” play heightened versions of themselves, Lillian follows its middle-aged namesake as she imperturbably handles the overwhelming responsibilities in her busy home in Richmond, Virginia, where she’s rearing four children under the age of ten—three foster kids and her granddaughter—and taking care of three bedridden, elderly live-in patients. “This is my life. This is what I want to do,” Lillian states in the off-screen narration that punctuates the film, a characteristically straightforward declaration by a woman who dispenses tough love to her young and old charges alike. Williams’s movie is an unrushed, unsentimental portrait of a gentle yet resilient matriarch; its best segments are vivified by the unscripted reactions of the kids, one of whom would be the subject of Williams’s next project, Thirteen (1997), also in the MoMA lineup.

Thirteen, 1997, directed by David D. Williams. Image courtesy the artist.

In Christian Blackwood’s enthralling documentary All by Myself: The Eartha Kitt Story (1982), the tiny, slinky diva hailed by Orson Welles as “the most exciting woman alive” emerges as another kind of fierce materfamilias. As she and her daughter, then nineteen, swan around the Waldorf Astoria at an event celebrating Reagan’s inauguration, Eartha brags of her only child, “She got into Barnard at a 3.7. She’s studying political science and the computer machine.” Kitt’s grandiloquent pronouncements offstage (“Today is a rather upheavaling day”), delivered in her singular mix of purr and crypto-Continental accent, are often indistinguishable from her haut-camp verbal stylings while onstage.

Eartha Kitt in All by Myself: The Eartha Kitt Story, 1982, directed by Christian Blackwood. Image courtesy Christian Blackwood Productions.

Despite Kitt’s skilled blurring of person and persona, Blackwood’s chronicle also captures the entertainer in moments of unvarnished immediacy. After the director has the audacity to ask his subject off-camera, “If a man came into your life, wouldn’t you want to compromise?” Kitt, long divorced and in her fifties at the time, erupts into terrifying, galvanic laughter. The cackles suggest emetic release, her ejecta rightfully targeted at the fool who dared pose such a question. Later, as Blackwood films Kitt in the South Carolina hamlet where she endured a wretched childhood, what shocks the most isn’t the cabaret legend’s sobs as she recounts the neglect (and worse) she suffered, but the fact that her voice is shorn of all Euro-affectation.

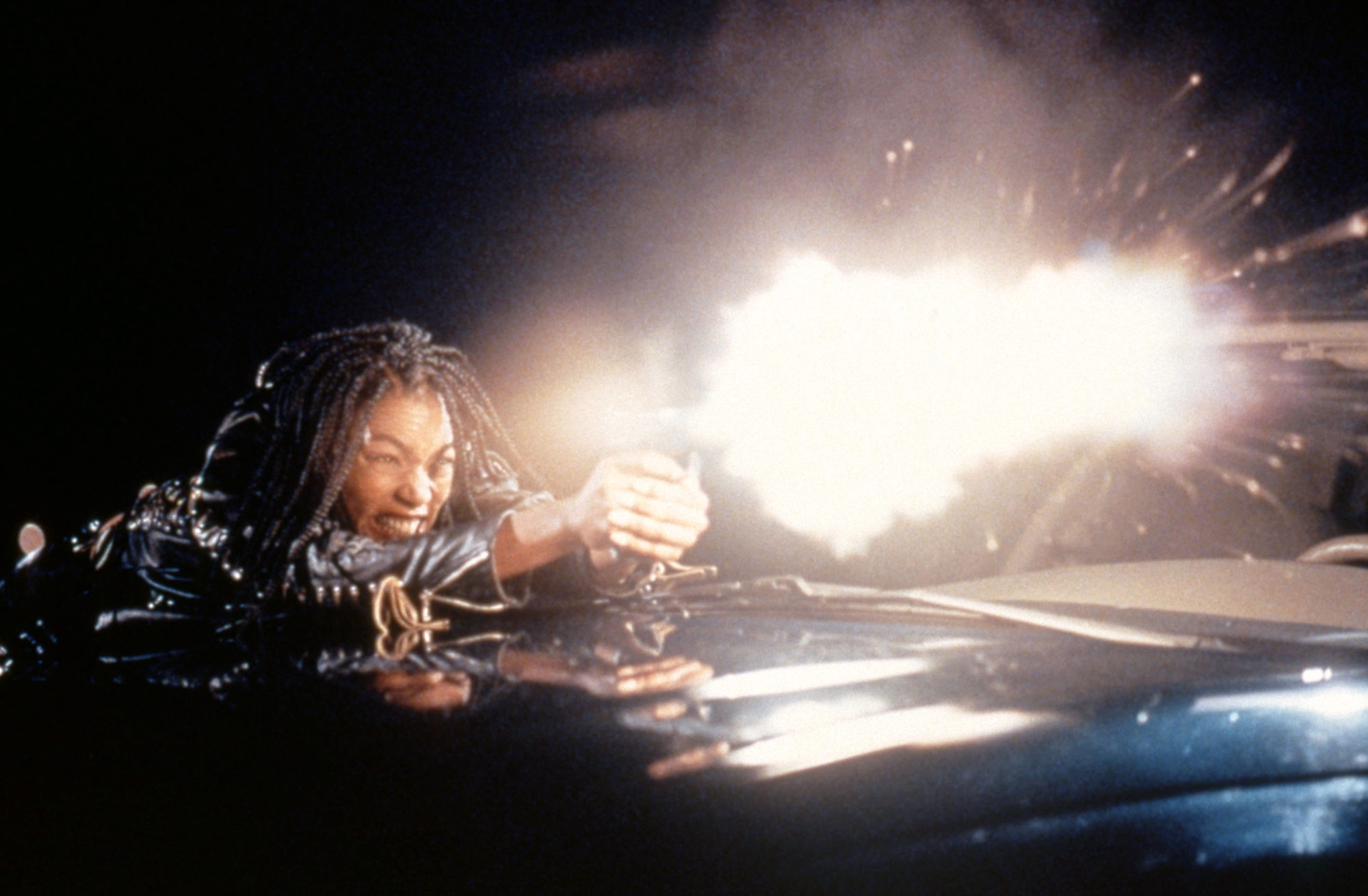

Angela Bassett as Lornette in Strange Days, 1995, directed by Kathryn Bigelow. Image courtesy Everett Collection.

Perhaps the biggest star in the MoMA series is Angela Bassett, here featured in two movies: Kathryn Bigelow’s apocalyptic triumph from 1995, Strange Days (also included in the Film Forum retrospective), in which the actress, playing a chauffeur and bodyguard of unremitting integrity, forms a dynamite dyad with Ralph Fiennes’s debased vice cop; and John Sayles’s densely populated social drama Sunshine State (2002), a film I revisited for the first time since its initial release. Then as now, Bassett rivets as Desiree, a recently married infomercial actress living in Boston who reluctantly returns, after twenty-five years away, to the tight-knit Florida community where she grew up. Her departure, we eventually find out, was more an exile; Desiree’s parents, pillars of the town, sent their daughter packing for a teenage transgression.

Bill Cobbs as Dr. Elton Lloyd and Angela Bassett as Desiree in Sunshine State, 2002, directed by John Sayles. Image courtesy Sony Classic Pictures.

“I don’t like who I am down here,” Desiree tells her spouse, Reggie (James McDaniel), who’s accompanied his wife for emotional succor. Watching Bassett negotiate her character’s various selves reveals a performer exquisitely balancing still-searing shame and rage with hard-won self-regard. It’s the kind of fine-grained role I wish more filmmakers would write for Bassett—who can play every woman, any woman.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns.