Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

An ambitious survey of American art that locates both hope and precarity in the mutability of the present moment.

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept, installation view. Photo: Ron Amstutz. Pictured, far right: Duane Linklater, a selection from the series mistranslate_wolftreeriver_ininîmowinîhk and wintercount_215_kisepîsim, 2022.

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept, curated by David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards, with Mia Matthias, Gabriel Almeida Baroja, and Margaret Kross, Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York City, through September 5, 2022

• • •

The 2022 Whitney Biennial is the most curated edition in some time—its organizers, the museum’s own David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards, have an argument to make. Finding themselves with an extra year to prepare the show (albeit under the least amenable circumstances), the pair have created a biennial that eschews the mere presentation of a snapshot of the US art world. Laudably ambitious, this exhibition is a reflection, at a juncture that feels very much like a turning point in our history, on past, present, and future—how we got here, where we are, and where we might be (or could be) going. Grief and hope operate in equal measures.

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept, installation view. Courtesy the Whitney Museum of American Art. Pictured, left to right: Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, The Word, 1975; Mouth to Mouth / Vide o me / Re Dis Appearing, 1987; White Dust From Mongolia, 1980; Permutations, 1976.

A number of themes—or, as the curators call them, “hunches”—animate the selection of sixty-three artists and collectives, whose work is installed primarily on the Whitney’s fifth and sixth floors. These hunches include the idea that abstraction might offer a visceral understanding of the world; that a contemporary “lush conceptualism” relies not so much on the dematerialization of the object as on a doubling down on the object’s thingness; that “auto-ethnographic” work goes beyond memoirish minings of the self, locating the subject in histories, cultures, networks, and systems of power; and that language has the capacity (both as a mode of communication and as a sign system) to narrate and complicate at once.

Coco Fusco, Your Eyes Will Be an Empty Word, 2021 (still). HD video, color, sound, 12 minutes. Image courtesy the artist and Alexander Gray Associates.

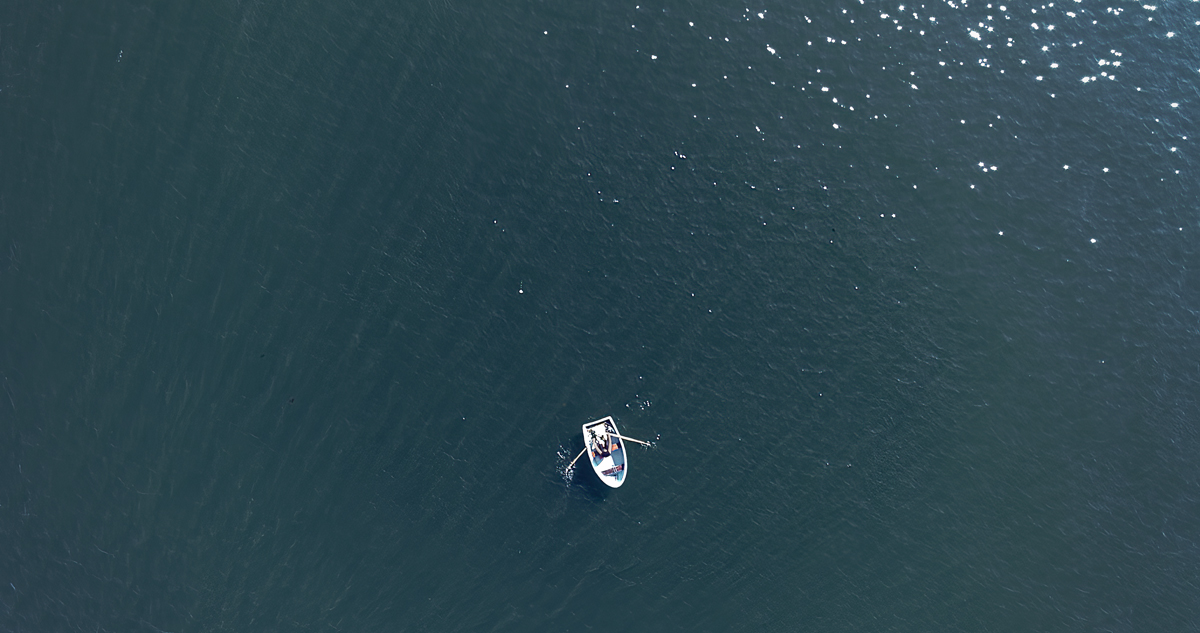

History is an overriding concern—in the curators’ eyes, the past is always coming into being and acting upon the present. Breslin and Edwards treat as unfinished business the infamous 1993 Whitney Biennial—the one that exemplified a broader turn in American culture toward the identity politics that we see taken up anew in our contemporary moment. Coco Fusco, Renée Green, Daniel Joseph Martinez, Trinh T. Minh-Ha, and Charles Ray, all included in that earlier iteration, appear again in 2022. The curators refer in the catalog to these and others in the show—Ralph Lemon, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Steve Cannon (known for his East Village gallery and publication A Gathering of the Tribes)—as ghosts who haunt the contemporary art world, exerting their presence in ways that are not always acknowledged. I question whether Ray truly functions in this manner; his recent resurgence seems to me less about relevance than market forces. But in other instances, the curators’ case is more convincing. Take, for example, a mini-retrospective on the fifth floor of Cha’s photography, video, film, and writing. Cha’s interdisciplinary practice has been explicitly cited by Trinh, and forms the basis of Na Mira’s affecting video Night Vision (Red as never been) from 2022 on the sixth floor. Another artist who seems particularly resonant right now—Coco Fusco—is represented by a 2021 video, Your Eyes Will Be an Empty Word, in which she grieves what COVID has taken from us by rowing a boat around Hart Island, site of a public cemetery where people, including those who died in epidemics up to and including our current one, have been buried, often anonymously, by prison laborers since the mid-nineteenth century. It is an exercise in confronting the present by confronting the past.

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept, installation view. Pictured: Leidy Churchman, Mountains Walking, 2022. Oil on linen, handcrafted wood easel, three canvases, 6 1/2 × 13 feet each. Courtesy the artist, Rodeo, and Matthew Marks Gallery.

Precarity, change, open-endedness, and the provisional are leitmotifs of our times, and of the exhibition, too. A number of works embody these conditions in their very form: Jason Rhoades’s Sutter’s Mill (2000), in which a structure made of aluminum pipes is dismantled and reconstructed weekly over the course of the biennial; Pao Houa Her’s photographs, which seek to create collective memories for her Hmong community in Minnesota, and will be swapped out during the show; Leidy Churchman’s Mountains Walking (2022), a three-panel, mural-like painting, which borrows its scale and look from Monet’s Water Lilies and is mounted on wheels; Alex Da Corte’s ROY G BIV (2022), where the enclosing frame of a screen—on which appears a video of the artist playing roles including Marcel Duchamp drinking out of a Johns ale can and one of the figures in Brâncuși’s The Kiss—is painted different colors in an ongoing performance by Da Corte’s housepainter brother. These themes show up again in art that addresses borders as fragile, shifting, but also violent exertions of power and sovereignty. Particularly effective here are Mónica Arreola’s photos of the Valle San Pedro near the Tijuana border, focusing on abandoned housing projects, and—one of my favorite pieces in the show—Juárez Archive (2020–) by Alejandro Morales, a deceptively simple array of novelty keychains, each containing a 35mm slide of a scene of the border (many taken from Google street views).

Alejandro “Luperca” Morales, Juárez Archive (7512 Maravillas Street), 2020–. Novelty magnifying keychain containing 35mm slide, 2 5/16 × 1 1/2 × 1 3/8 inches each. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Michelle Lartigue.

It’s when mutability and instability operate as mere metaphors that the curators lose me in their otherwise exemplary offering. This is especially the case with the exhibition design. The two floors are conceived as two sides of a coin: the sixth as a labyrinth of black-painted, low-lit rooms and the fifth an open, airy space in which art—including a large number of abstract paintings—is displayed on moveable, skeletal supports. The organization of the fifth floor has its advantages, including allowing the works to “speak” to each other without walls to interrupt their conversations and evoking the makeshift nature of the art fair as well as an earlier era of rough-and-tumble, artist-driven exhibitions, the kind that used to exist before fairs became big business. But there are disadvantages, too: a visual cacophony that occasionally turns paintings into mere backdrops for what is installed around them or inadvertently dampens their force. The first of these problems is especially unfortunate in the case of Duane Linklater’s excellent natural-dyed pieces that recall traditional patterns for teepee coverings. The stitched-together semicircular panels, hung from a rod from the ceiling, fuse modernist idioms of material abstraction—think Sam Gilliam and Helen Frankenthaler—with approaches to abstraction that derive from the artist’s Omaskêko Ininiwak heritage. The second issue is most apparent with respect to Churchman’s mural on casters: the artist’s aesthetic decision to make a moveable painting is neutralized by the number of paintings on the floor that are not installed on fixed walls.

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept, installation view. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

I will end at the beginning, in a sense: with a room on the sixth floor that the curators refer to as an antechamber—a space of transition where one can take a moment, as it were, to breathe. Dark and moody, the room is indeed organized around the idea of breath. The curators have filled it with three things. I will not talk about one of them—a shrouded piece installed high on the wall, almost invisible, that is left purposely unidentified; it seems churlish, almost like a spoiler, to tell you what it is given Breslin’s insistence in his catalog essay that the “the story of this object is not [his] to tell.” The only thing to see clearly in the space is a small vitrine that contains a vial reputed to hold Thomas Edison’s final exhalation, gathered on the inventor’s deathbed on behalf of Henry Ford, and now part of the collection of the Henry Ford Museum. Also present—not visible, but present—is one of the most haunting sound pieces I’ve ever encountered: Raven Chacon’s Silent Choir, consisting of recordings the artist made at the No Dakota Access Pipeline protests at Standing Rock in 2016 and 2017. Instead of the expected din of resistance, we hear the respiration of the crowds, the occasional surveillance helicopter whirring overhead, the rustling of bodies. This is the interval before or after action—a recouping of energy, perhaps, or a moment of deciding how to proceed, calm and tense by turns. After a stretch of time during which George Floyd’s last words rang in our ears, during which millions around the world were felled by a disease that attacked our lungs, during which we have been holding our breath—letting out a sigh of relief on occasion—as we watch our political landscape transform, I was grateful to have a chance to contemplate this most basic sign of life.

Aruna D’Souza is currently Edmond J. Safra Visiting Professor at the National Gallery of Art and a contributor to the New York Times and 4Columns. She is the editor of the newly released book on Linda Nochlin, Making It Modern (Thames & Hudson, 2022). She was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.