Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

A powerful retrospective of over one hundred works presents the artist’s reckonings with apartheid, whiteness, guilt, and loss.

William Kentridge: In Praise of Shadows, installation view. Courtesy the Broad. Photo: Joshua White / JWPictures.com.

William Kentridge: In Praise of Shadows, organized by Ed Schad, the Broad, 221 South Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, through April 9, 2023

• • •

William Kentridge: In Praise of Shadows is a sprawling retrospective of the celebrated South African artist’s animated films, prints, bronze sculptures, theater models, installations, tapestries, and more on view at the Broad. Perhaps not surprisingly, since the work is part of the Broad’s collection, the show is built around The Refusal of Time (2012), a piece commissioned for Documenta 13. In a darkened room, five films are projected on the walls; at the center is a lumbering, bellowed, pistoned, wooden contraption moving back and forth on a track, which was inspired by pneumatic clocks, a nineteenth-century French innovation that sought to synchronize a city’s timepieces via compressed air running through underground tubes.

William Kentridge, The Refusal of Time, 2012. Five-channel video installation, four steel megaphones, and breathing machine (“elephant”). Courtesy the Broad.

The behemoth seems to inhale and exhale, like a living creature, a breathing machine. Kentridge calls it “the elephant,” invoking Charles Dickens’s description in Hard Times of the pumping of a steam engine’s piston as “the head of an elephant in a state of melancholy madness.” Here, the mad elephant/machine’s brute force and violent potential is aligned with the ultimate purpose of those pneumatic clocks and other attempts in the late 1800s to create a globally standardized chronology. Whether this involved the truing of clocks so workers showed up for their shifts and trains ran efficiently, or the imposition of time zones so that the business of empire could be rationalized, the project was a crucial aspect of the cruelty of both industrialization and colonialism. The films—composed of live-action, animated, and found footage—move forward and backward so that a drawing or collage is suddenly unmade or an action is reversed, or are fractured through cuts and sutures, or show two identical scenes slowly falling out of sync. By replacing the ticking of a clock with the elephant’s quasi-corporeal cycle of inhalations and exhalations, and by using cinema’s capacity to complicate our sense of time’s inevitable forward march, Kentridge puts paid to mechanized time, and in that way refuses to hew to the power of the metropole.

William Kentridge, The Refusal of Time, 2012 (detail). Five-channel video installation, four steel megaphones, and breathing machine (“elephant”). Courtesy the Broad.

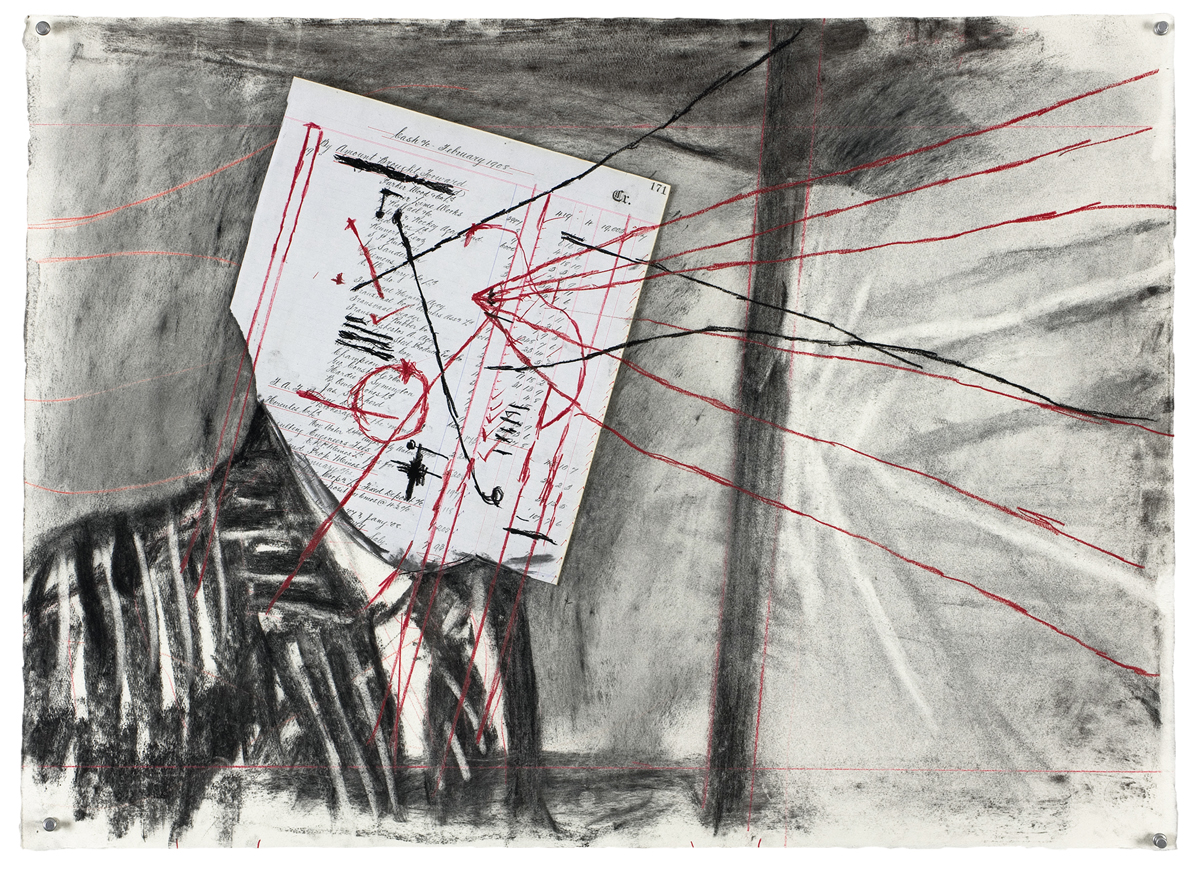

In this exhibition, which includes around 130 works made over the past thirty-five years, the artist takes up not only timepieces, but also maps, stereoscopes, cameras, landscape drawings, ledger books, dictionaries—measuring, recording, and standardizing instruments of all kinds. His scrutiny of such tools and devices—tools and devices that are central to his art-making—serves to lay bare their European roots and their use in the colonial project, and thereby cast a shadow on the histories they have documented, especially South Africa’s shameful history.

William Kentridge, drawing for the film Other Faces, 2011. Charcoal and colored pencil on paper, 22 1⁄2 × 31 inches. Courtesy the Broad Art Foundation.

Among these varied recording devices, the most important is Kentridge himself. The artist—a descendant of a patrician family of Lithuanian Jews who immigrated to South Africa at the time of its founding, whose parents were deeply involved in the anti-apartheid struggle—has witnessed the brutality and eventual collapse of that system of racial segregation and its political aftermath. Zakes Mda, writing in the catalog, calls Kentridge’s approach an “autobiography in the third person” for the way in which he uses himself—his perspective, his body and its movements, his own distorted memories, all translated into visual form—as yet another imperfect, even compromised, lens through which to process and capture the turbulence of South Africa’s (and the continent’s) colonial past and postcolonial present.

William Kentridge: In Praise of Shadows, installation view. Courtesy the Broad. Photo: Joshua White / JWPictures.com. Pictured: City Deep, 2020. HD video.

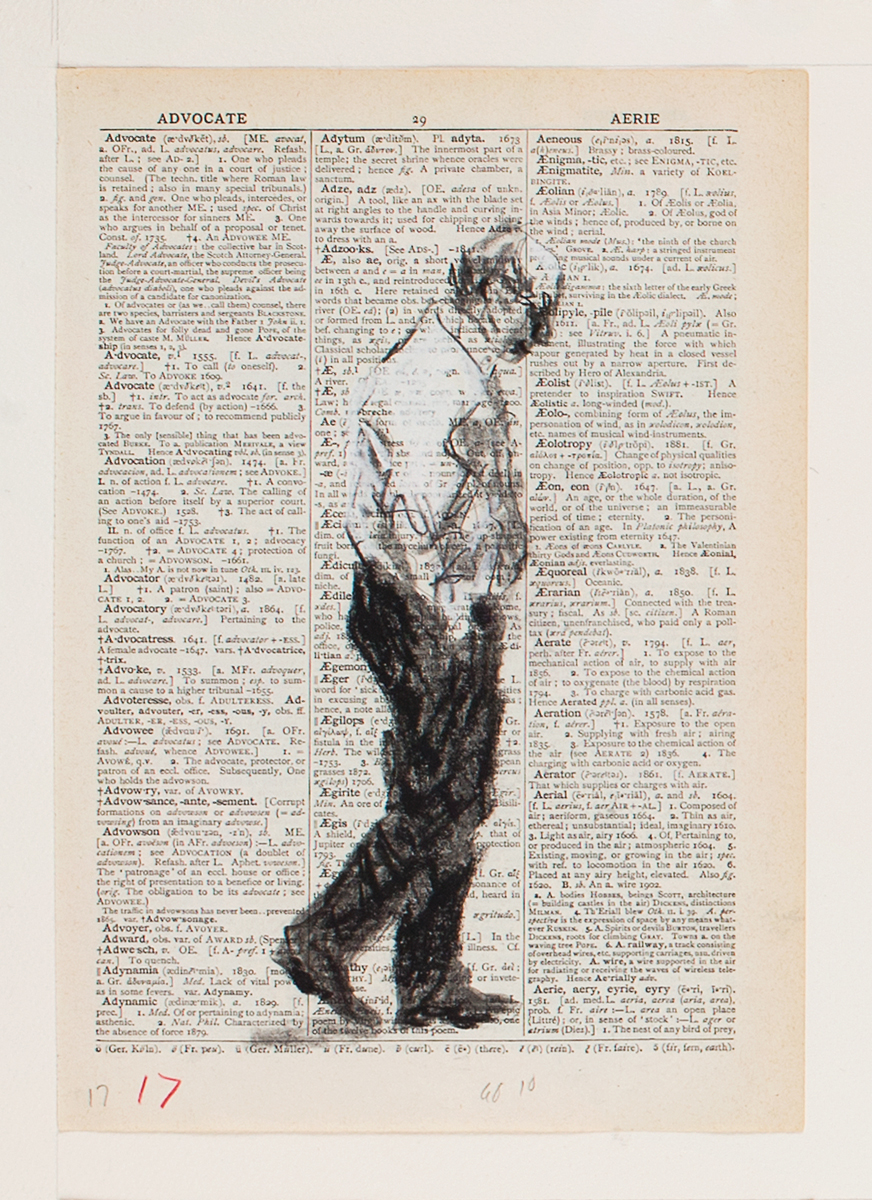

In the charcoal, pastel, and gouache drawing Flood at the Opera House, from 1986, a time when the apartheid system was beginning to crack under the pressure of protest, it is Kentridge’s own eyes that we see in a rearview mirror, surveying a scene of decadence and debauchery that seems to come straight out of George Grosz’s or Max Beckmann’s pictures of Weimar Germany. Self-portraiture lies at the heart of some of Kentridge’s most famous and beloved works: the eleven animations in the ongoing series Drawings for Projection (1989–), which are made by filming successive states of charcoal drawings, each image rendered and then erased so that the traces of past iterations are carried into the next. Two of its main characters—Soho Eckstein and Felix Teitelbaum—are his alter egos. Kentridge is the face of Eckstein’s wealth and privilege, and then of the crumbling of his power and his crisis of conscience and his mourning and his inability to take in the monumentality of the societal shifts of his country—the narrative that plays out across the series. The artist also lends his countenance to Eckstein’s foil, the humane and loving Teitelbaum. In the suite of etchings Ubu Tells the Truth (1996–97), created in conjunction with a puppet show Kentridge directed after South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established, his own naked figure appears trapped by or in control of the outlined figure of Alfred Jarry’s cruel, vulgar, and gluttonous king. It is Kentridge, rendered in charcoal, pastel, and ink, who strides, stands, paces, and mounts and descends chairs on the pages of the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary in the diptych Let Us Enter the Chapter (2013) and the related flipbook film Second Hand Reading (2013). His image is interspersed with short, resonant phrases: “Thinking on one’s feet” (Kentridge speaks often of the simultaneity of moving, ideating, and the image- and object-making that happens in the studio); “Man is a walking clock” (an evocation of embodied time); “Fixing the moment” (a play on how cameras and other recording devices fix an image, as well as the idea of repairing the damage caused by past sins).

William Kentridge, Let Us Enter the Chapter, 2013 (detail of diptych). India ink, charcoal, pastel, and digital print on Shorter Oxford English Dictionary paper tabbed to Velin d’Arches 400 gsm paper. Courtesy the Broad.

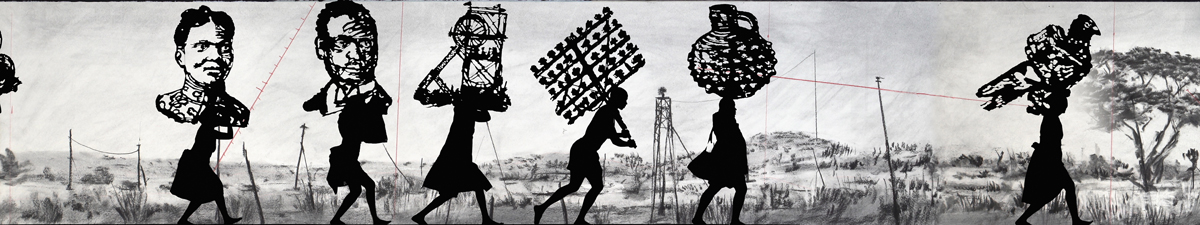

Among these phrases is “He that fled his fate,” a shortened version of a saying that often pops up in the artist’s work: “He that fled his fate went forward to meet his destiny.” The words point to the futility of sidestepping the difficult process of grappling with history. The exhibition is indeed filled with images that set out to contend with the horrific events that have shaped South Africa’s current conditions. Severed heads of political dissidents pile up piteously in Casspirs Full of Love (1989). The plunger of a French press coffeepot drills down into the earth, past more severed heads, past miners in showers, past miners in sleeping barracks that look like morgues, to an image of a slave ship’s hold in the animated film Mine (1991). The African porters who were exploited by European powers during World War I trudge across the landscape in the installation Kaboom! (2017–18). (The Head & The Load, a performance that debuted at the Park Avenue Armory in 2018, also took up this theme.) But as powerful as these visual reckonings are, it is the image of the white man, of Soho Eckstein–cum-Kentridge himself, dealing with his own culpability, anger, impotence, and sense of loss in relation to South Africa’s racist policy, that is indelible to me.

William Kentridge, Kaboom!, 2017–18. Three-channel HD film installation with model stage, paper props, found objects, and three mini-projectors with stands. Courtesy the Broad.

I cannot think of a white American artist, male or female, who has wrestled with the individual and collective guilt adhering to the US history of slavery or its aftermaths in the same unstinting way as Kentridge does with European colonialism and apartheid—Philip Guston is the only person who comes close, I suppose. I laughed at first when I read the director’s note in the exhibition catalog touting the fact that this was Kentridge’s first US retrospective in over ten years—how often should an artist be the subject of a retrospective, really?—but on second thought, perhaps this is exactly the work that white and white-adjacent America needs to see, over and over again, until it finally makes the connections between its present—mass incarceration, police brutality, gerrymandering and redlining, the January 6 riots, and so much more—and a past that it too often refuses to claim as its own.

Aruna D’Souza is the 2022–23 W. W. Corcoran Professor of Social Engagement at the Corcoran School of Art and Design in Washington, DC and a contributor to the New York Times and 4Columns. She was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.