Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

A collection of autobiographical writings by the late Janet Malcolm, inspired by photographs from the journalist’s past.

Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory, by Janet Malcolm, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 155 pages, $26

• • •

Janet Malcolm’s essays are true in a way that shows how others lie. Writing is persuasion, after all, the agitations of which often do little more than alert you to their presence. Malcolm knew this, and saw that truth only reads as such when the teller enlists her agitations. Malcolm’s posthumous memoir, Still Pictures, is dense, unadorned, and casually confessional about the truth of the truth. “When I ask someone a question—either in life or in work—I often don’t listen to the answer,” Malcolm states. “I am not really interested.” It’s hard to imagine another writer of her caliber (I thought of Didion) admitting this.

Malcolm was forced to think about how truth becomes publicly true during the ’90s spectacle that made her famous, unusually so for a journalist. Almost ten years of litigation with Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson over allegedly libelous statements she made in a New Yorker piece brought her in contact with her own “arrogance” (her word) and taught her that scarves mattered to a jury as much as anything else. For the second and final trial in 1994, she turned her chair toward the jurors so she could play to them as well as opposing counsel. (She won.) Still Pictures is Malcolm turning almost entirely toward us.

Malcolm and her editor, Ileene Smith, had talked often about the possibility of a memoir, but in 2010, Malcolm published “Thoughts on Autobiography from an Abandoned Autobiography” in the New York Review of Books, a very brief bulletin that seemingly put paid to the idea. In the second of four paragraphs, she writes: “If an autobiography is to be even minimally readable, the autobiographer must step in and subdue what you could call memory’s autism, its passion for the tedious.” This is how Malcolm plates her truth: the what of it, followed by the how.

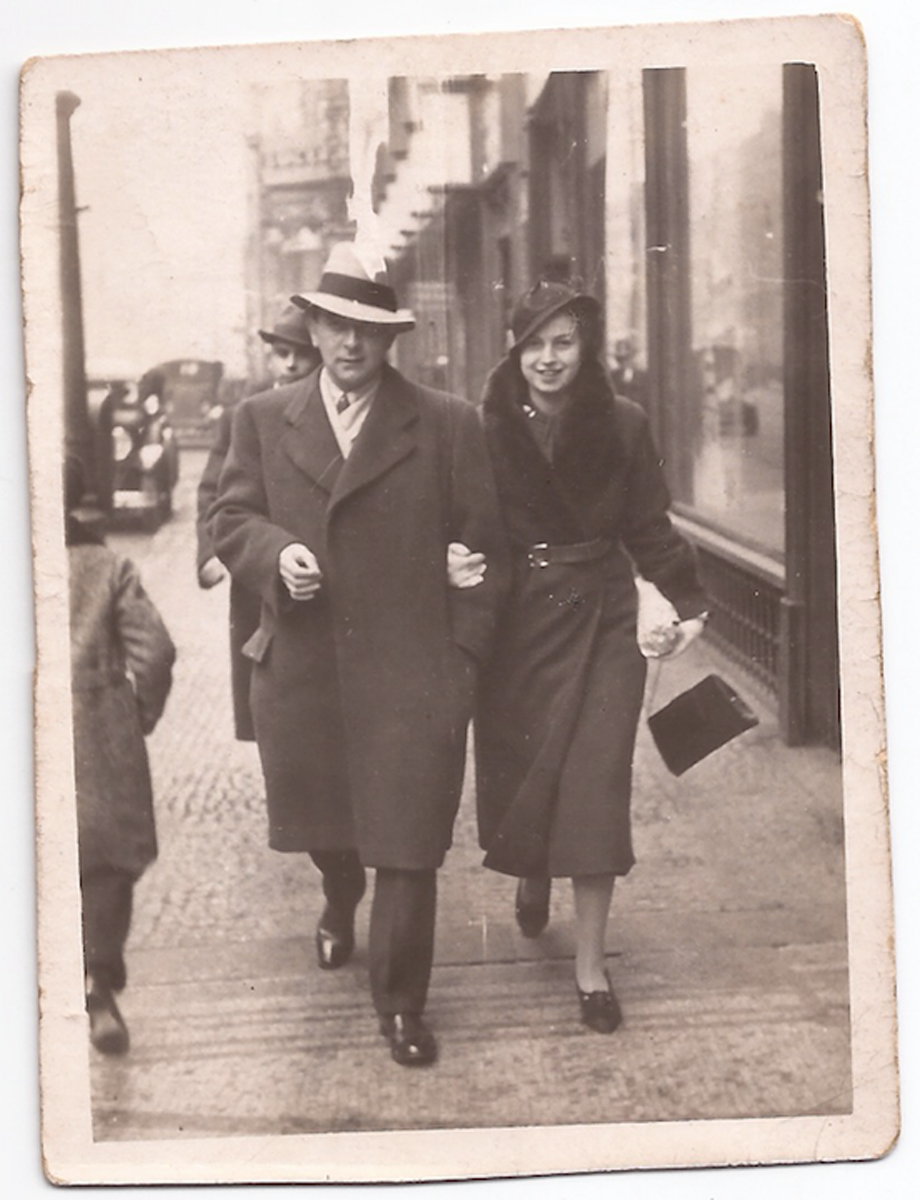

Malcolm’s parents, in Prague. From Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory. Courtesy the author.

Malcolm rarely spoke in public. She did no promotional appearances, did not solicit blurbs for her books, and refused a New York Times Magazine profile. But she kept thinking about her own story. In 2016, Malcolm called Smith and said, “I found a box called Old Not Good Photos. And they’ve unlocked something. I’ve started to write from these photographs and I don’t know what it is. Maybe it’s a memoir, maybe it’s not a memoir, but I’m going to keep going.” For the next few years, she regularly sent these pieces to her friends, her daughter, and Smith; some of them were published in the New Yorker. Six about her childhood and Czech relatives were grouped together into one piece, and one about her family’s place (literally) in the pecking order of the opera house was published alone. All of them are aggregated in Still Pictures, the last book she wrote before her death in 2021.

Malcolm with a camera, date unknown. From Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory. Courtesy the author.

Malcolm herself points out that “Old Not Good Photos” is an “understatement.” Most are “two-and-a-half-inch squares, showing little blurred black-and-white images, taken from too far away, of people whose features you can barely make out.” The book’s printing does little to enhance them; they are prompts you can easily ignore. In the poverty of its images, Still Pictures is very different from Malcolm’s other major photography work, her very first book, published in 1980: Diana and Nikon, a collection of her ’70s columns for the New Yorker when she was its photography critic. That self-serious book about the Photo Secessionists (who knew?) and Irving Penn’s use of platinum prints discusses famous and weighty images. The more relevant model is Burdock, from 2008, the only book of Malcolm’s own photography. It is brief and odd, a coffee-table vision of leaves taken from the medicinal weed, many of them suffering a blight of some kind. In it, she writes, “I prefer older, flawed leaves to young, unblemished specimens—leaves to which something has happened.” Beauty and truth in photographs didn’t ultimately coincide for Malcolm. She cites Avedon and the fact that he “radically extended photography’s capacity for cruelty.” One imagines a “Malcolm” setting in Apple Photos that creates a slideshow using only the most upsetting images in your library.

Malcolm at two or three years old. From Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory. Courtesy the author.

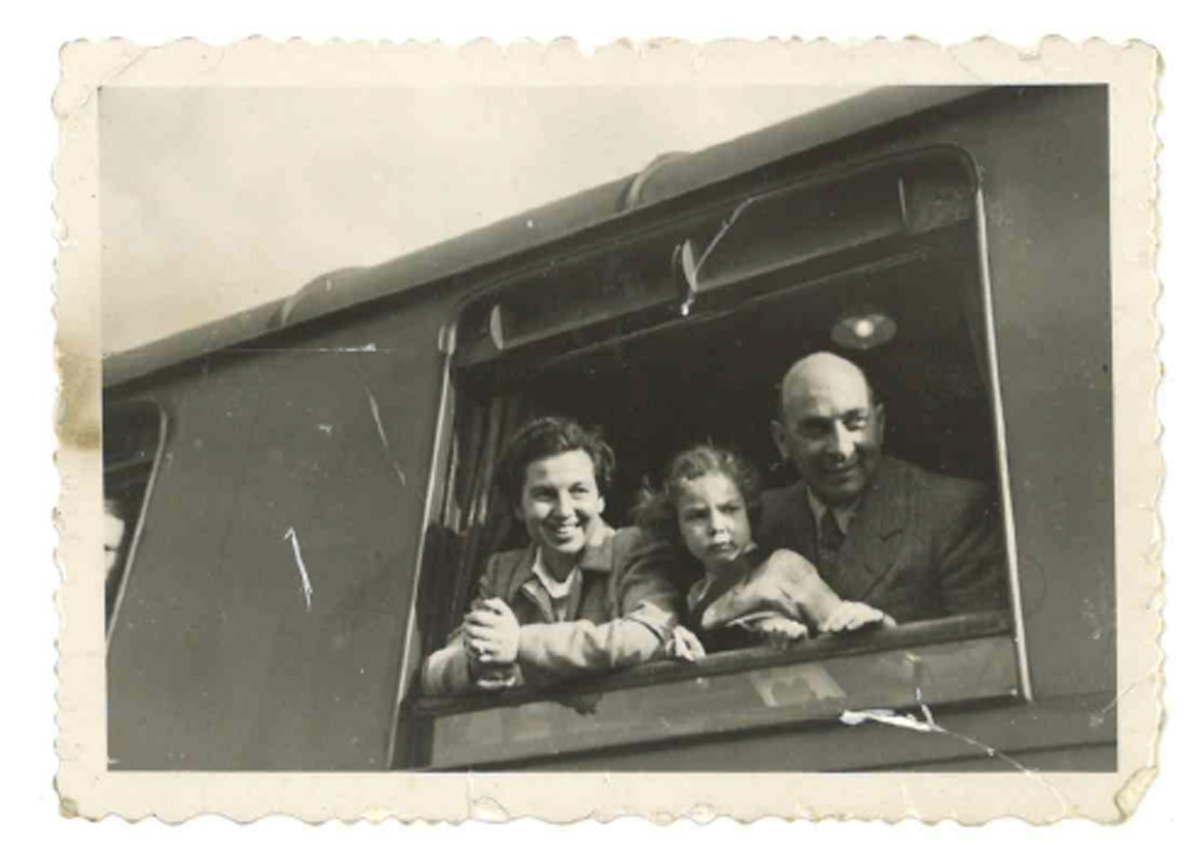

Malcolm begins Still Pictures as someone to whom things have happened. She has prefaced this section, like a soldier laying landmines, with a truly adorable picture of herself, exact age unknown, smiling in a polka-dotted bonnet and onesie. She recalls being a small child in the former Czechoslovakia, participating in a “village festival.” (Malcolm was born there in 1934; her family fled Nazi persecution for New York City in 1939.) All of the girls are carrying baskets of rose petals, but not Malcolm. A “kind aunt” comes to her aid and hands her a basket of “hastily” plucked peony petals. Apparently a skeptic already as a toddler, Malcolm feels “cheated” by this “counterfeit” replacement. She puts her memory on the stand: “Was being given petals from the ‘wrong’ flower so afflicting because it set me off from the other children, making me seem different?” She is already impossibly special: “When I recoiled from the peony petals, had I stumbled on some knowledge of the natural world otherwise not available to a child of five?” The experience convinces Malcolm, well into adulthood, that the rose is the “queen of flowers.” Was it just that the tiny Malcolm had been embarrassed, an emotion available to all children? Perhaps normalcy was the least appealing fate, and the more attractive truth was that she had a neurotic response to peonies that merited endless litigation only she could adjudicate.

Malcolm (middle) with her parents as they depart from Prague in 1939. From Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory. Courtesy the author.

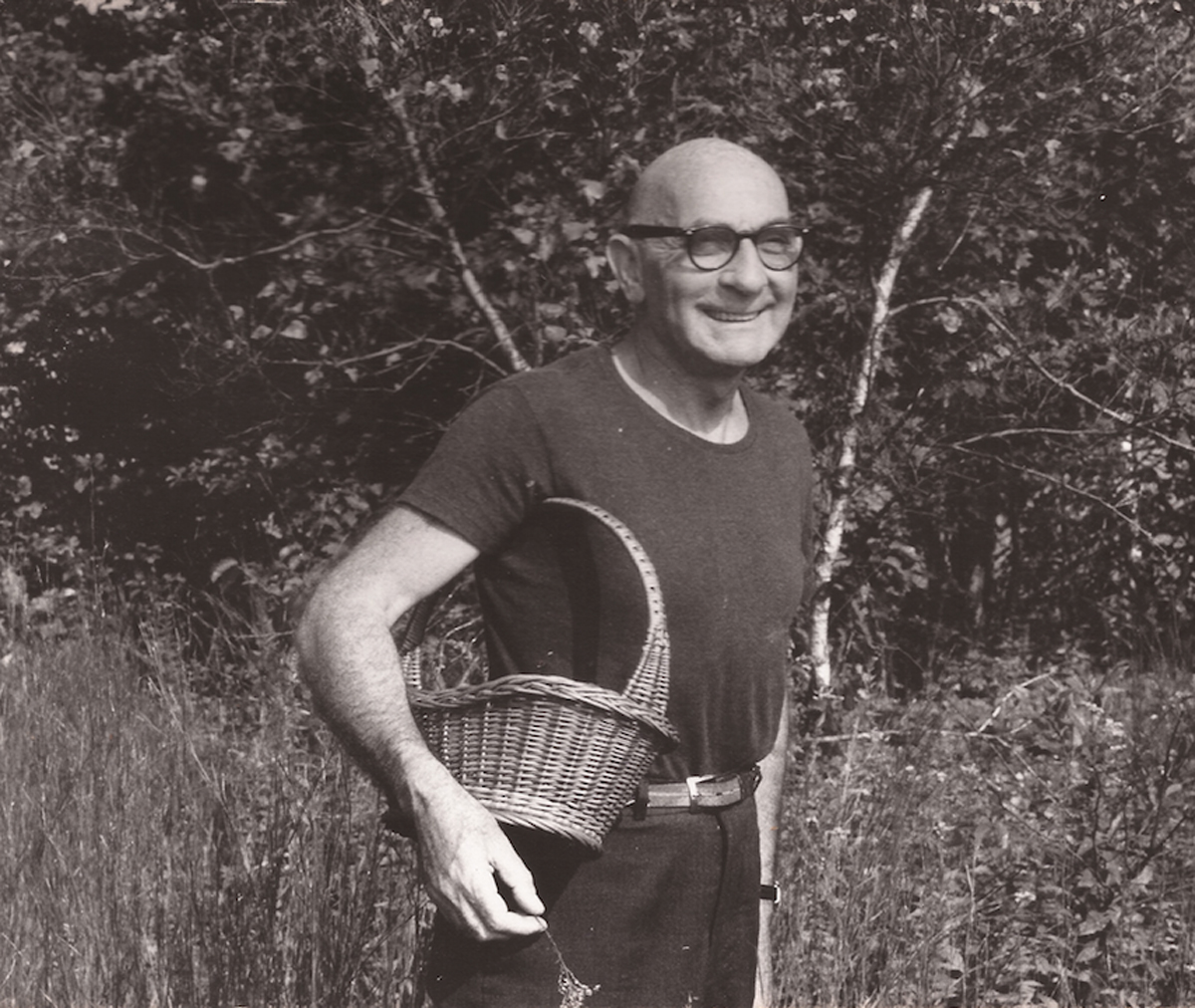

Malcolm is not unwilling to discuss the details of her life; it may have simply been the memory of her parents that forestalled the act of writing a memoir. They appear nowhere in her work as they do here. Malcolm does not protect them when they buy ill-fitting suits or excuse them when they handle friendships poorly. Right after telling us her father—“Daddy” is the title of the chapter—was “the gentlest of men,” she addresses the jury: “Parents have their mythologies.” One of her father’s few tall tales was a story about his prodigious independence, and Malcolm does not let it live untagged: “How was a ten-year-old boy able to live alone in a big city? Where had he lived? Was he really completely on his own?” The untruth here is mild—her father had not been a Dickensian waif but a kid who “lived with relatives.” It doesn’t come across in her telling as much of a lie. Yet the inaccuracy mattered, possibly because her father’s otherwise immaculate honesty was her first model for truth-telling. The chapter ends with a page of affection that she does not qualify. Malcolm begins, “he loved opera, birds, mushrooms, wildflowers, poetry, baseball. I am flooded with things I want to say about him.” She finishes the chapter by showing us that her attention to the smallest of truths did not clash with her love for him: “He liked to pick and identify certain small, frail, white wildflowers that it never occurred to me to notice, and that he never forced on my attention.”

Malcolm’s father. From Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory. Courtesy the author.

In fact, loving her father was tied to her fundamental and somber belief that a shared truth can be properly adjusted, perhaps the only purpose of writing: “My mind is filled with lovely plotless memories of him. The memories with a plot are, of course, the ones that commit the original sin of autobiography, which gives it its vitality if not its raison d’être. They are the memories of conflict, resentment, blame, self-justification—and it is wrong, unfair, inexcusable to publish them.” She does not, ultimately, publish any of the resentments she held against her father. She turned away from us and took those with her.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York. His memoir, Earlier, will be published by Semiotext(e) in the fall of 2023.