Darryl Pinckney

Darryl Pinckney

The legendary ’70s–’80s gallery and incubator of Black avant-garde artists showcased in a striking MoMA exhibition.

Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Emile Askey. Pictured, far left on back wall: Susan Fitzsimmons, Hang Ups: Rocks from Downstate, 1979. Lucite, pants hanger, and the artist’s hair at age twenty-six. Partition wall in foreground, left to right: Senga Nengudi, R.S.V.P. Fall 1976, 1976/2017. Nylon mesh, sand, and pins. David Hammons, Untitled Reed Fetish (Flight Fantasy), circa 1978. Phonograph record fragments, hair, bamboo, plaster, colored string, and clay. Far right on back wall: Suzanne Jackson, MaeGame, 1973. Acrylic wash on canvas.

Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, curated by Thomas (T.) Jean Lax with Lilia Rocio Taboada, in collaboration with Linda Goode Bryant and Marielle Ingram; Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through February 18, 2023

• • •

Free your ass and your mind will follow, people used to say. In 1974, Linda Goode Bryant, then the director of education at the Studio Museum of Harlem, opened Just Above Midtown—the subject of an exhibition now at the Museum of Modern Art—on West Fifty-Seventh Street. JAM’s location was a provocation, a black-owned gallery among the street’s established white-owned galleries, a black-owned gallery that was a part of the “alternative spaces” movement and right there down the street from Carnegie Hall and the Russian Tea Room. What was happening in Manhattan then had everything to do with the history of its real estate. The policies and apathy behind urban vacancy and community decay made possible the arrival of the culturally new. Buildings that had little value, structures that were underused or just waiting, met people who had the vision to honor the city’s unspoken creed: you are here to be somewhere you have not been before.

Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Emile Askey. Pictured, far left on plinth: Camille Billops, Untitled (lamp). Engraved terra-cotta lamp. Far right, on platform foreground: Camille Billops, Madame Puisay, 1981. Glazed earthenware.

Linda Goode Bryant was an entrepreneur of art who perceived a hole in the cultural landscape shaped like her. She stepped into it. Her clarity was characteristic of her politically informed avant-garde intentions: to bring institutional and commercial visibility to black artists whose professional opportunities were otherwise limited. Goode Bryant recalls in the 2017 catalog for the exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power that she wanted a place where she could escape “whiteness,” and express what were to her racially different values. Synthesis, the group exhibition with which Just Above Midtown first announced itself, included both representational and nonrepresentational works. Camille Billops, Vivian Browne, Dan Concholar, Alonzo Davis, David Hammons, Suzanne Jackson, Norman Lewis, Valerie Maynard, Russ Thompson, and Randy Williams: some names better known than others; and names that also speak of a generational mix.

Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Emile Askey. Pictured, far right: Noah Jemison, Black Valhalla, 1976. Encaustic on canvas.

To mix things up was an aspect of JAM’s experimental thrust. White artists exhibited in the gallery, but as an alternative space it retained its black cultural nationalist aura because of that funny thing back then whereby a few black people in a white setting constituted integration, while a few white people in a black setting didn’t change that setting’s identity as black. David Hammons’s 1975 show, Greasy Bags and Barbeque Bones, presented grease-stained shopping bags and sculptures of kinky hair to address, among other things, the centrality and shame of grease and oil and ashy skin in black grooming. It freaked so many people out that Goode Bryant famously staged a discussion among viewers on the spot the first night. She was interested in the spirit of art as much as its objects and images.

David Hammons, Untitled, 1976. Grease and pigment on paper, 29 × 23 inches. Courtesy the Hudgins Family Collection. © David Hammons.

What is black art? The question was both uncomfortable-making and emboldening, like the prevailing assumption of the period that assigned the burden of the racially symbolic to the representational and bestowed intellectual prestige and the future on the nonrepresentational. Goode Bryant, as she tells it, inclined toward the abstract, but the paths of exploration she advocated in that tradition were various and answered her ambition to make Just Above Midtown a dynamic junction for new artists and new audiences, a theater of ideas, a laboratory of aesthetics. Its projects became ever more conceptual, and in addition to exhibitions and lectures, the gallery sponsored performances, readings, screenings. Goode Bryant and her team had a knack for creating events. Trouble also knew her name, as Baldwin would say, but JAM survived for over a decade, moving in 1980 from West Fifty-Seventh Street to Franklin Street in Tribeca, and then going in 1984 from that location to Broadway in Soho. Two years later Just Above Midtown closed.

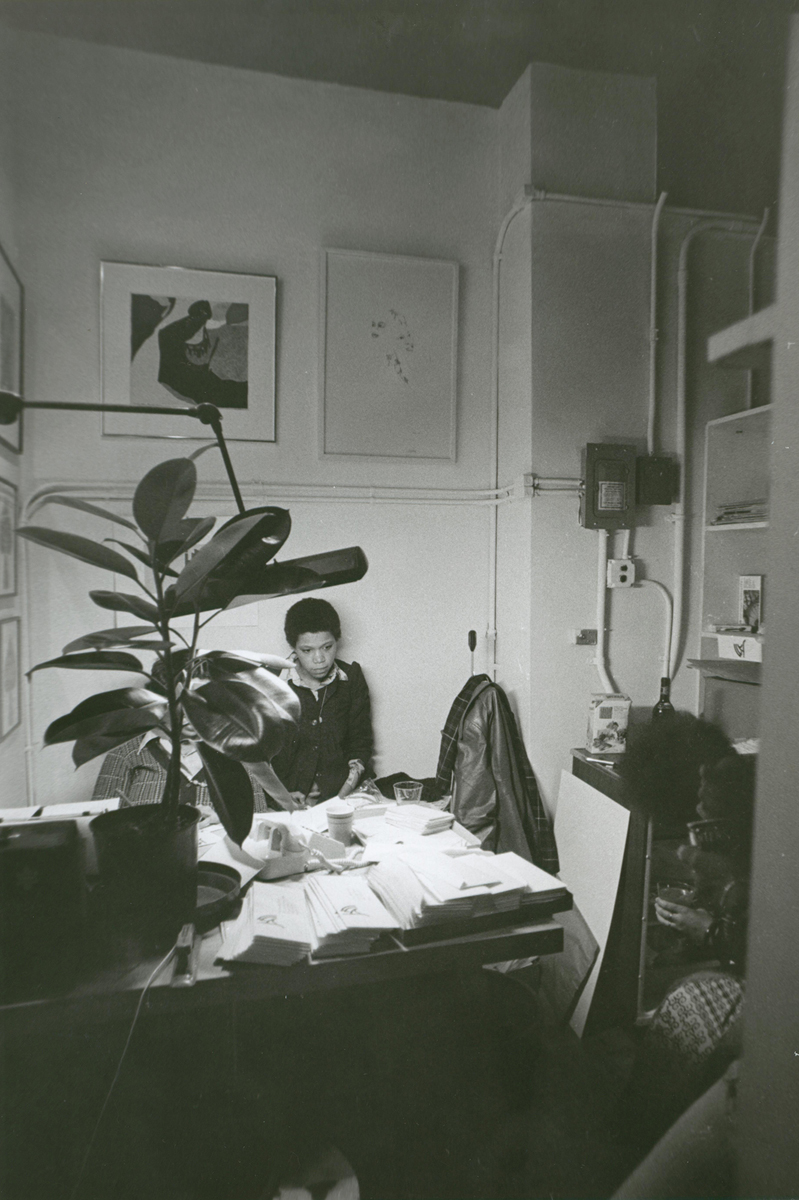

Linda Goode Bryant and Janet Olivia Henry (obscured) at Just Above Midtown, Fifty-Seventh Street, December 1974. Courtesy the Hatch-Billops Collection. Photo: Camille Billops.

MoMA’s exhibit Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces says, No, no, trouble did not win. The number of artworks on view is a surprise. Here is the story of JAM as it moved around, a missing link–like chapter of the New York postwar avant-garde told in the roster of its artists, the range of their styles, the diversity of their media. (The catalog, edited by Thomas (T.) Jean Lax and Lilia Rocio Toboada, is outstanding, even essential for a full understanding of Just Above Midtown.) Everywhere evidence of attitudes toward materials that converted the artist’s having to make do into the artist’s flipping off convention.

Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Emile Askey. Pictured, left wall, left to right: Howardena Pindell, Untitled #87b, 1977. Cut-and-pasted and painted punched paper, acrylic, watercolor, thread, mat board, sprayed adhesive, and string on paper. Randy Williams, L’art abstrait, 1977. Wood, canvas, book, book cover, plexiglass, wire, metal bolts, and lottery ticket. Right wall, back left corner: Wendy Ward Ehlers, Untitled (Three Inches Equals One Week of Laundry), circa 1974. Lint in Plexiglas box. Right wall, center: Sydney Blum, SWARMS four, 1980. Fabric, rubber flies, acrylic paint, grommets, and other media.

Randomly: Senga Nengudi’s wall sculpture R.S.V.P. Fall 1976 greets the viewer with suspended, sand-filled nylon mesh that evokes the testicular. In one black-and-white film, Howardena Pindell is talking about her work as she prepares, punching paper, accumulating a little mound of small circles, and not far away from the screen hangs her Untitled #87b from 1977, a mat board of densely applied cut and painted punched paper.

Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Emile Askey. Pictured, far left: Lorna Simpson, Screen 4, 1986. Wooden accordion screen, gelatin silver prints mounted on panels, and vinyl letters. Right wall: Sandra Payne, twelve untitled drawings from the series “Most Definitely Not Profile Ladies,” 1986. Ink on colored paper.

Every work is a door. Even the ones that seem like they are about to disappear. Knock. Randomly: Palmer Hayden, Cynthia Hawkins, Sandra Payne. In 1979, Susan Fitzsimmons showed a composition made of a clothes hanger and her hair, Hang Ups: Hair. Randy Williams’s powerful collage from 1982, AIDS Not So Holy, is postcard, wood, metal, books, paper, acrylic paint, plexiglass, condom. He searched the streets for stuff to use, this “Neo-Dada” former student of Hale Woodruff’s. There is Betye Saar, and who knew that Barbara Chase-Riboud, early novelist of the Sally Hemings story, was also a visual artist. Noah Jemison, Mallica “Kapo” Reynolds; Jean Moutoussamy-Ashe’s arresting portraits from South Africa. A beautiful, shining, freestanding accordion screen by Lorna Simpson is hard to leave. This is the kind of exhibition that has a lot to tell us and trusts that it will have the time and the space in which to do so.

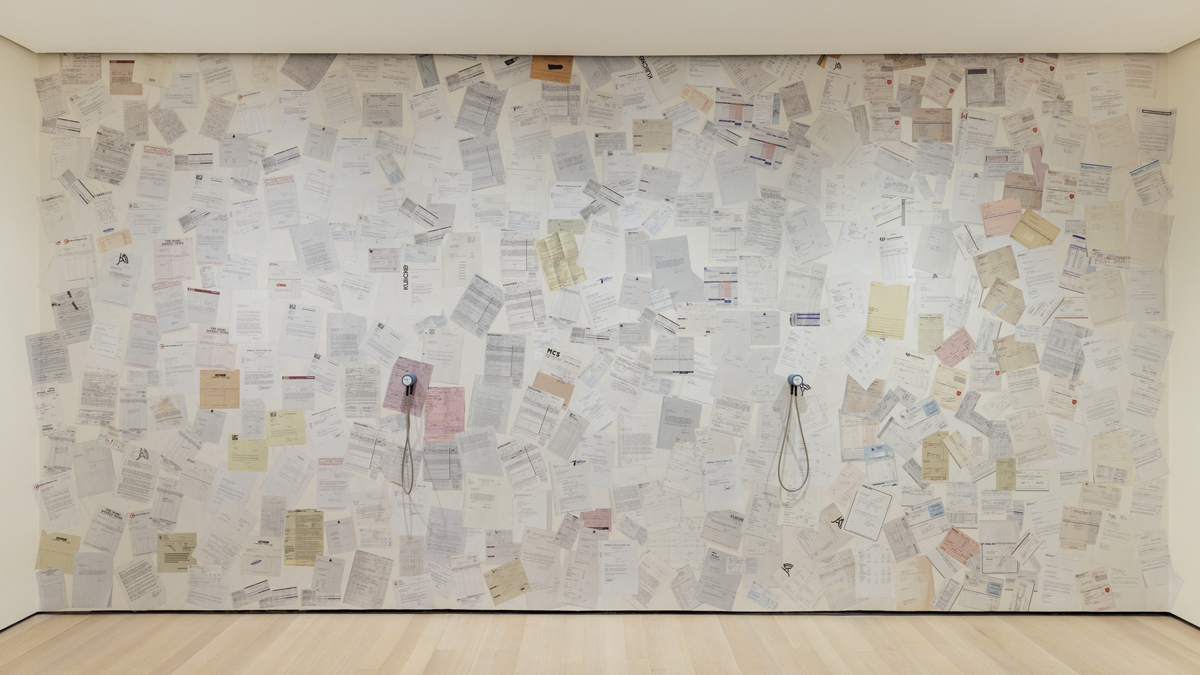

Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Emile Askey. Pictured: Past-due bills issued to Just Above Midtown, circa 1970–80s. Wallpaper.

The sense of scene is very strong, everything in conversation with everything else: oil on canvas, works on paper, painted paper bags, photographic prints, slides on a light table, mounted newsprint, ceramics, a plexiglass receptacle of dyed lint (Wendy Ward Ehlers), socks made of rubber flies (Sydney Blum), and films of an installation or of a multimedia theater piece or of a black artist (Noah Jemison) painting on a large piece of paper on his floor while in the nude. There is a whole wall of letters and notes begging JAM to pay its bills. Goode Bryant says she embraced debt. O that avant-garde tradition. What is most striking is how joined in common cause the representational and the nonrepresentational in African American art are when seen in retrospect. Fifty years have gone by. Time brings unity and inspires a further openness.

Darryl Pinckney is the author of two novels, High Cotton (1992) and Black Deutschland (2016), and four works of nonfiction, Out There: Mavericks of Black Literature (2002), Blackballed: The Black Vote and US Democracy (2014), Busted in New York and Other Essays (2019), and, most recently, Come Back in September: A Literary Education on West Sixty-Seventh Street, Manhattan (2022).