Catherine Damman

Catherine Damman

Race, AIDS, and the Institute of Snap!thology: a look back at the innovative filmmaker.

Still from Affirmations (1990), by Marlon Riggs. Image courtesy Signifyin’ Works and Frameline Distribution.

“Race, Sex & Cinema: The World of Marlon Riggs,” the Brooklyn Academy of Music, 30 Lafayette Avenue, Brooklyn, February 6–14, 2019

• • •

“It don’t hurt,” he says, with the vocal equivalent of a buttery, conspiratorial wink. The referent in question is anal penetration. The shot is tight, and the speaker, Reginald T. Jackson, drapes himself assuredly on the stoop. In the background, a gospel choir swells. Jackson’s chronicle of sexual encounter—by turns sweet and feline—opens Affirmations (1990), a roughly ten-minute short by Marlon Riggs. From the narrative specificities of individual experience, the screen segues to the work and exhilaration of plurality, showing footage from the African American Freedom Day parade in Harlem. One chant gets stuck in my head: “We’re black black black black gay gay gay gay.”

This refrain thrums throughout Riggs’s oeuvre. Watching, one senses the felt exigency of collective enunciation; taken together, the films form a chorus of first-person interviews and overlaid voices quoting from poetry, literature, and history. Riggs, however, always registers the inconstancies within what might otherwise be called “identity”—a person’s jangling apprehensions and chary internal dissents—teasing out the small differences to constitute not a theory of narcissism, but rather a careful meditation on all of kinship’s wobbles and churns. This crystallizes in the aforementioned parade scene: a man is swept away by the mantra, his body rocking, fists pumping. Around him, other men intone the words, but with more attenuated enthusiasm. Sometimes the necessary task of organizing gives back the buzz and gratification of assembly; other times it has to be enough just to do the work.

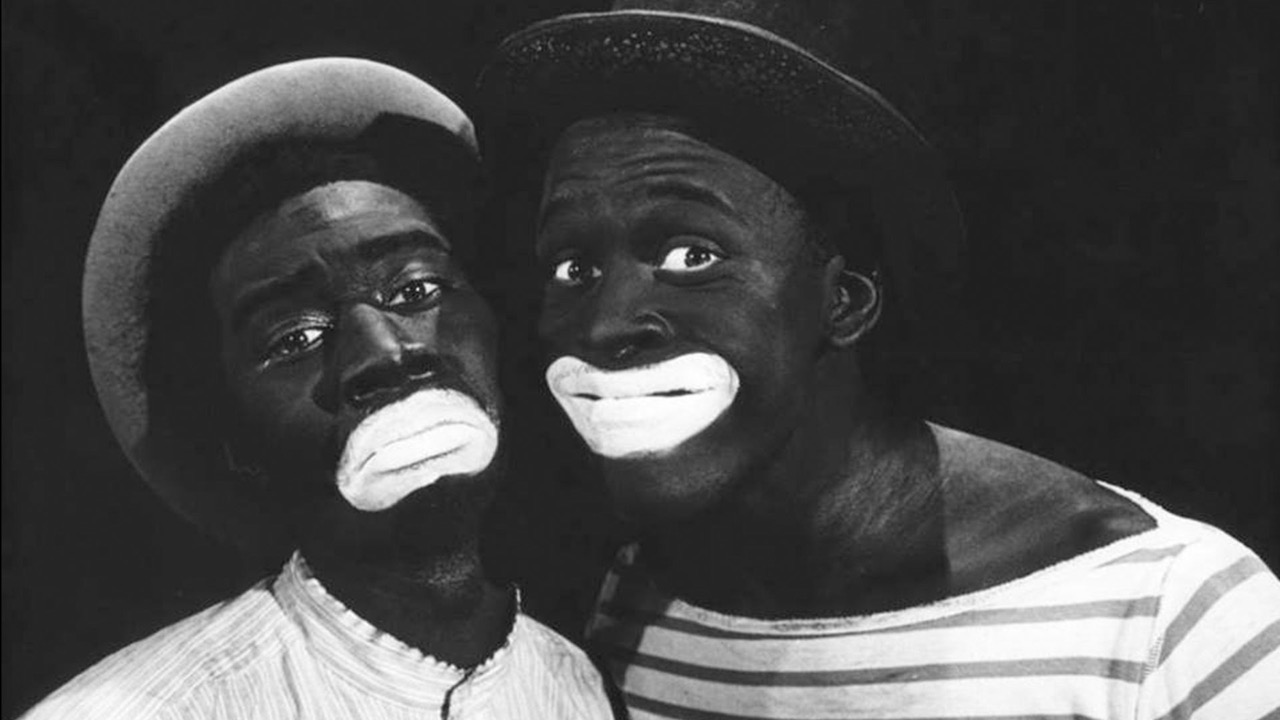

Still from Ethnic Notions (1986), by Marlon Riggs. Image courtesy California Newsreel.

Riggs first came to widespread attention in 1986 with Ethnic Notions, for which he won an Emmy. In his filmography, it forms a kind of companion to Color Adjustment (1992); both mobilize the documentary form’s quiet air of authority to scrutinize representations of African Americans in popular culture. Ethnic Notions focuses on antiblack stereotypes from the antebellum period on, tracing the visual culture of white supremacy in its baldest depictions. In one scene, scholars discuss the rhetoric that figured the heinous institution of slavery as “a kind of paradise.” A disembodied narrator parrots this position, saying, “I am quite sure they never could become a happier people than I find them here”—just as the curdling voice lands on the locative deictic, the screen cuts. The prints of racist, smiling cartoons have disappeared; in their stead is the image of a real man, known as Gordon, as seen in an indelible 1863 photograph that catalogs slavery’s actual hellishness through the scars that traffic his back. Here.

Still from Color Adjustment (1992), by Marlon Riggs. Image courtesy California Newsreel.

Perhaps you have seen this photograph, which was circulated widely, mobilizing photography’s evidentiary claims to advance the abolitionist cause. So Riggs’s filmmaking knows the gaping need for irrefutability. Yet his work just as often juxtaposes the factual might of the document with more alchemical powers, the magic of editing. In Color Adjustment, which turns its media-critical lens to broadcast television, footage from The Cosby Show depicts the Huxtables, cozy in their eat-in kitchen, while text—imposing rudely in the manner of a news ticker—explicates the rates of systemic black poverty and joblessness.

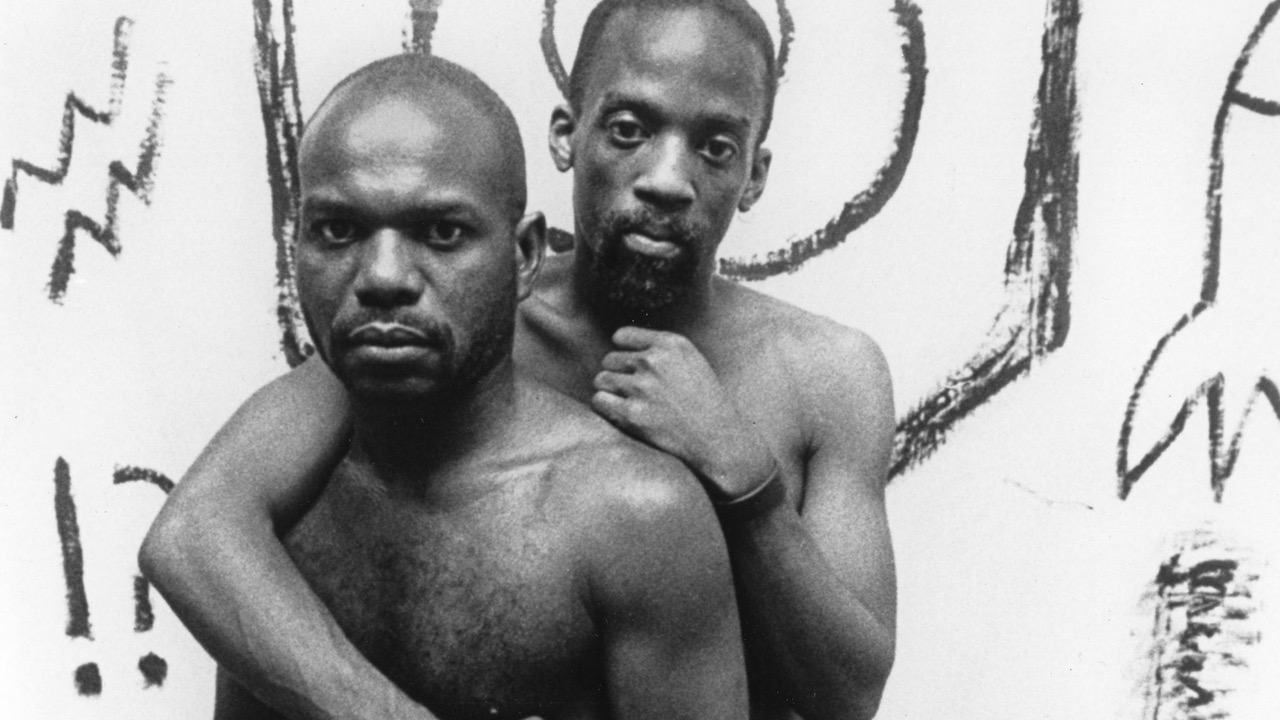

Still from Tongues Untied (1989), by Marlon Riggs. Image courtesy Signifyin’ Works and Frameline Distribution.

In between these two films, Riggs made Tongues Untied (1989), for which he is best known, not least because it became mired in NEA controversy and targeted by conservative, homophobic fearmongering—attacked by Jesse Helms, weaponized in Pat Buchanan’s presidential campaign. Its daring lies in both its figuring of unabashed homoeroticism and its formal experimentation. In one scene, the viewer encounters a group of men as in a black-box theater; they treat the audience to “a basic lesson in snap,” that is, in emphatic gesticulation. This demonstration comes “courtesy of The Institute of Snap!thology,” an invented, glittering authority designed to initiate the spectator into the snap’s variations: medusa, sling, point, mini and maxi, and classic. “Don’t get it twisted,” one voice warns, with a coquettish, knowing timbre that suggests, it will, inevitably, get twisted.

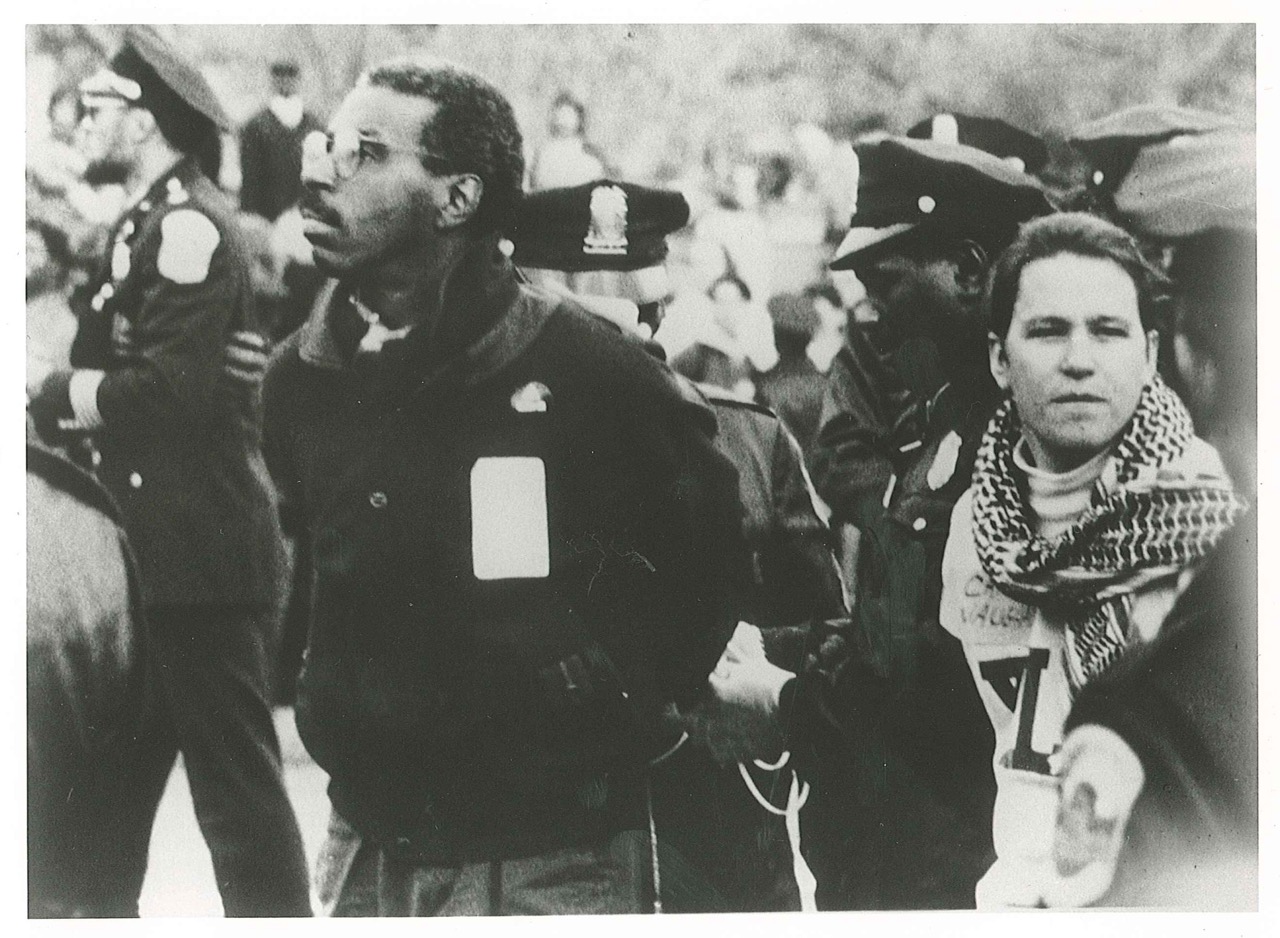

Still from Anthem (1991), by Marlon Riggs. Image courtesy Frameline.

The foul knowledge that gay black life is continually degraded even as the culture it produces forms the fons et origo of everything cool likewise suffuses Anthem (1991), another short. It offers the music video’s injection high—a throbbing rhythm carries shots of a rose’s interior to those of lit candles, fingers dipping into a jar of Vaseline, leather vests adorning bare chests, and lips glossed in a deep rouge color that, a few years later, would become a fashion bestseller called “vamp.” In an essay from 1991, Riggs tackles the ways that appropriation “deflates the gesture into rank caricature,” tussling with Hollywood’s depiction of what he terms “Negro Faggotry.” Reading, I remember that the tip of the tongue is also called a blade.

Still from Non, je ne regrette rien (1993), by Marlon Riggs. Image courtesy Signifyin’ Works and Frameline Distribution.

Non, je ne regrette rien (No Regret, 1993) was made as part of the Fear of Disclosure project, so named for a video tape Phil Zwickler made with David Wojnarowicz in 1989. Black video mattes, the kind used in news segments to preserve anonymity, at first obscure the speakers’ faces, showing only isolated mouths and eyes as they discuss divulging their HIV status. Later, the effects dissolve, as if to literalize the process of revelation. The camera trains its eye on their hands; the men talk about their mothers. Equally affecting is the film completed by Riggs’s crew after he died of AIDS-related illness in April 1994. Black Is . . . Black Ain’t features a range of scholars and activists discussing a host of issues: colorism, Afrocentrism—feeling black whether wearing kente cloth or blue jeans—and what would today be referred to as misogynoir. Riggs speaks to the camera from a hospital bed.

Still from Black Is . . . Black Ain’t (1994), by Marlon Riggs. Image courtesy California Newsreel.

The world is not yet good enough and there is still much to grieve. And, as one poem by Essex Hemphill, quoted in Tongues Untied, avers, “grief is not apparel,” neither easily worn nor shed. An unblinking love of poetry illuminates Riggs’s method, which permits the enjambments of lived experience. Another spoken fragment, heard in Anthem, instructs us to “conjugate a future.” Conjugation, of course, refers to the necessary inflections of grammar to accommodate differentiation just as much as it connotes the physical act of coupling. The films, too, are rapt to the textures of specificity, and to the ways that erotic congress can be life-making—perhaps especially so—when not in the service of literal reproduction. Riggs’s work insists on the primacy of pleasure while also attending to the unrelenting pain of social origin. I think of the marchers in Affirmations, radiant through the streets of Harlem, and how the camera lingers on the glowering face of one man, who brays his fury at their existence from the sidelines. It still hurts.

Catherine Damman is an art historian and critic. Her writing on experimental dance, theater, film, music, and the visual arts can be found in Artforum, Bookforum, Art in America, Art Journal, and elsewhere. She completed her PhD at Columbia University and is currently an Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at Wesleyan University’s Center for the Humanities.