Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan

“My tears met yours in the ditch / America”: a new collection of poems from Shane McCrae.

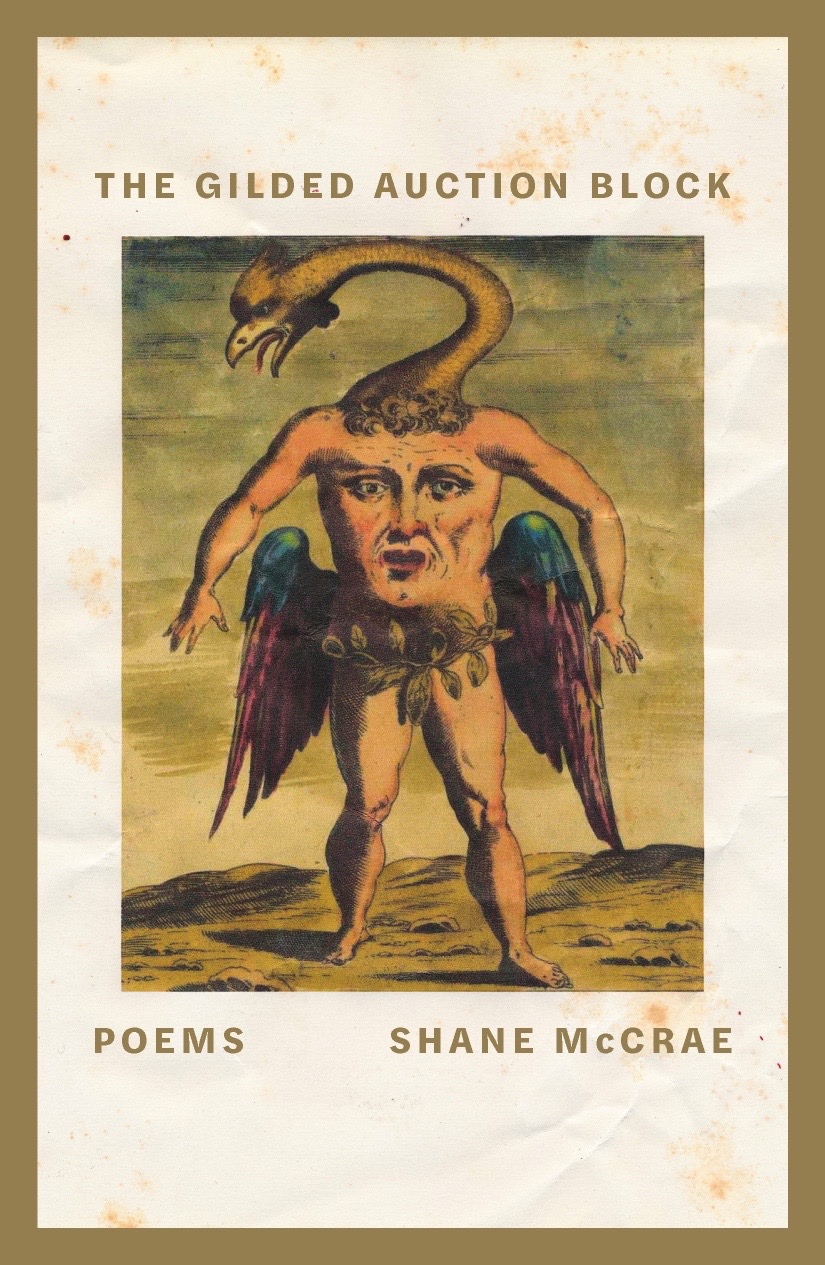

The Gilded Auction Block, by Shane McCrae, 92 pages, $23

• • •

In the poems of Shane McCrae, language weighs as heavily in the mouth as it does on the mind. Try reading any of the seven collections he’s published over the past nine years and you may find yourself short of breath and achy of jaw, whether or not you’ve actually been reading aloud. Where centuries of poetic tradition have led us to idealize the art form as something akin to music, McCrae regularly upends our expectations of mellifluousness, delivering line after line that sounds like it’s being forced through gritted teeth. His interest in linguistic estrangement is hardly new; jagged syntax, inexplicable repetitions, and unorthodox or nonexistent punctuation are common strategies among modern writers striving to denaturalize the power structures embedded in language. What’s driving McCrae’s choice of style, though, is the desire to realign perspective, as he draws us into uncomfortable intimacy with the most corrosive strains of our American vernacular.

His latest book, The Gilded Auction Block, starts off as a sweeping address to the nation, with a brittleness that echoes the grim inauguration speech Donald Trump delivered in January 2017. The president himself turns up as a recurring voice; in him, McCrae has found not just his muse but his competition, someone as capable as he is of twisting sentences into awkward and unrecognizable shapes. Tackling up-to-the-minute subject matter is no longer a guaranteed eyebrow-raiser in the poetry world—partly since it’s now more widely recognized that one person’s “topical” is someone else’s “everyday”—but that hasn’t made a project like this any less daunting a challenge. The epigraphs of several poems repurpose notorious Trump gaffes—his description of Frederick Douglass as “somebody who’s done an amazing job,” his blithely condescending praise of “the poorly educated.” McCrae does this in ways that foreground the writer’s dilemma: How to expose speech that is already so naked in its toxicity, whose implications have already been combed through by countless commentators? And how to imitate the ugliness of today’s political discourse without completely forsaking lyric beauty?

As with the best of McCrae’s work, the spark in these new poems lies not in their openings, which sometimes veer toward the heavy-handed, but in their unnervingly elegant resolutions. For all his attraction to opacity, McCrae knows how to write last lines that prick the heart and snap us into sudden perception. One of the highlights of the book, “Hatred,” treats love like a rug that’s been pulled out from under us: as the speaker watches the scene of a young Nazi flirting with a girl, he becomes “afraid / That if they loved each other I would see.” In “Forgiveness Grief,” McCrae reflects, as he has done in the past, on his relationship with the racist grandmother who raised him, and on how he has clung, however misguidedly, to “the harm you did to me” as an emblem of love. And finally, at the end of the book, he arrives at a kind of blunt anti-aphorism: “We live and die apart together.” Here, love is a knowledge too twisted to fully metabolize, one that tethers us to oppressors no less human than ourselves.

McCrae, who was born to a white mother and black father (“my skin / Is brown but brown like I might be Italian / Most often people think I’m Mexican”), shows us how the ideas governing our lives overflow the boundaries we seek to contain them in. He’s especially eloquent when observing, with an almost theological rigor, how familiar concepts—particularly the dichotomies of “black” and “white,” “love” and “hate”—become all the more amorphous in an unjust society. In these new poems, he recalls previous impassioned invocations of that battered old myth “America,” by everyone from Langston Hughes to Allen Ginsberg, using the nation’s name as a target for both his sympathy (“my tears met yours in the ditch / America”) and his contempt (“America I’m laughing can you hear me / I’m laughing when I heard you say you weren’t / Racist”). Echoing its predecessor, the 2017 tour de force collection In the Language of My Captor—whose centerpiece is a half-verse, half-prose section written partly from the point of view of Jefferson Davis’s mixed-race adopted son—The Gilded Auction Block is populated by the spectral figures of powerful white men: beyond Trump, there are cameos by Joe Arpaio and Jeff Sessions. Stretches of stuttering wordplay are further grounded by references to stereotypical middle-American settings: Walmart, Wendy’s, a mall in Austin.

Writing that revolves around so many archetypes—the “auction block” of the title appears in regards to a racist encounter the speaker (presumably McCrae himself) has while teaching at Oberlin—risks feeling predetermined, even when it’s setting out to destabilize the way we understand its subjects. But of course that stasis is one of his great themes, compelling him to navigate between the fixed notions that circumscribe his world and the subjective realities that can call them into question. Like his earliest influence, the Sylvia Plath of Ariel, McCrae has an affinity for the white-knuckle moods of psychodrama, yet within that constricted range, the approach is remarkably fluid. As in his other books, you’ll find an array of styles and modes here, including first-person confessionals, historically rooted monologues, and (in “The Hell Poem,” the book’s longest and least persuasive section) an extravagantly imagined infernal vision in which birds bark expletives and a giant beetle intones Trump-like boasts.

At times you can feel McCrae straining to broaden the scale on which oppression is depicted, to break it out of the typical autobiographical and sociological frameworks and see it for the intricate cosmology it is. Still, what fuels his most riveting moments are the smaller-voiced intensities, the sense of a narrator trying to wrest personal, sometimes shameful truths from a language that so often proves inadequate to conveying the inner lives of people of color. If The Gilded Auction Block is more inconsistent than McCrae’s previous work (a fair amount of which is astonishing), the cumulative impact is still a powerful thing to reckon with. Few poets of his generation have been able to slip between so many different registers of American English—the flatness and emptiness of Trumpian invective; the antique cadences of slave narratives; the raw emotional explicitness of much of contemporary political literature; the fractured hyperresponsiveness of social-media culture—to such unsettling effect. Through this disorienting mix of voices we hear our native tongue as both the inflictor of unspeakable damage and the scar that’s been left behind.

Andrew Chan is web editor at the Criterion Collection. He is a frequent contributor to Film Comment and has also written for Reverse Shot, Slant, Wax Poetics, and other publications.