Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Return of the anti-muse: new painterly fireworks from the veteran artist.

Joan Semmel: A Necessary Elaboration, installation view. Image courtesy Alexander Gray Associates.

Joan Semmel: A Necessary Elaboration, Alexander Gray Associates, 510 West Twenty-Sixth Street, New York City, through February 16, 2019

• • •

Always a rapturous colorist, Joan Semmel paints with extra abandon in her new suite of canvases. Passages of smoldering chiaroscuro give way to dusky pastel modeling or ultra-saturated backgrounds of crimson, turquoise, and chartreuse in the nine much-larger-than-life nudes of A Necessary Elaboration. These fresh examples of her signature approach to self-portraiture are suffused with euphoric resolve and executed with cool bravado, as the New York artist, now in her eighties, handily reprises or references key moments of her radical career.

Since the 1970s, Semmel has practiced a kind of liberated figuration, short-circuiting the male gaze by recasting the female nude as a self-observed subject, making clear the model is the artist herself. A favorite strategy: rendering her own foreshortened figure as she sees it, head and neck absent from the picture, breasts and torso and thighs like hills receding into the horizon. Two fiery yellow-orange-violet works from last year, which flank the gallery’s ground-floor stairway in a sunny welcome, fit this description. Another iconic leitmotif of Semmel’s is the inclusion of her camera or a mirror frame in the painting, tipping off the viewer to her autonomous process. Semmel, who always works from her own photographs, does not hold a viewfinder to her eye in these new images, but her dynamic compositions—which recall both in-camera cropping and the occluded views of direct or mirrored self-regard—still hint at her longstanding modus operandi. Those of us familiar with her legendary conceit are also attuned to its ever-evolving significance as her subject, her body, changes over time.

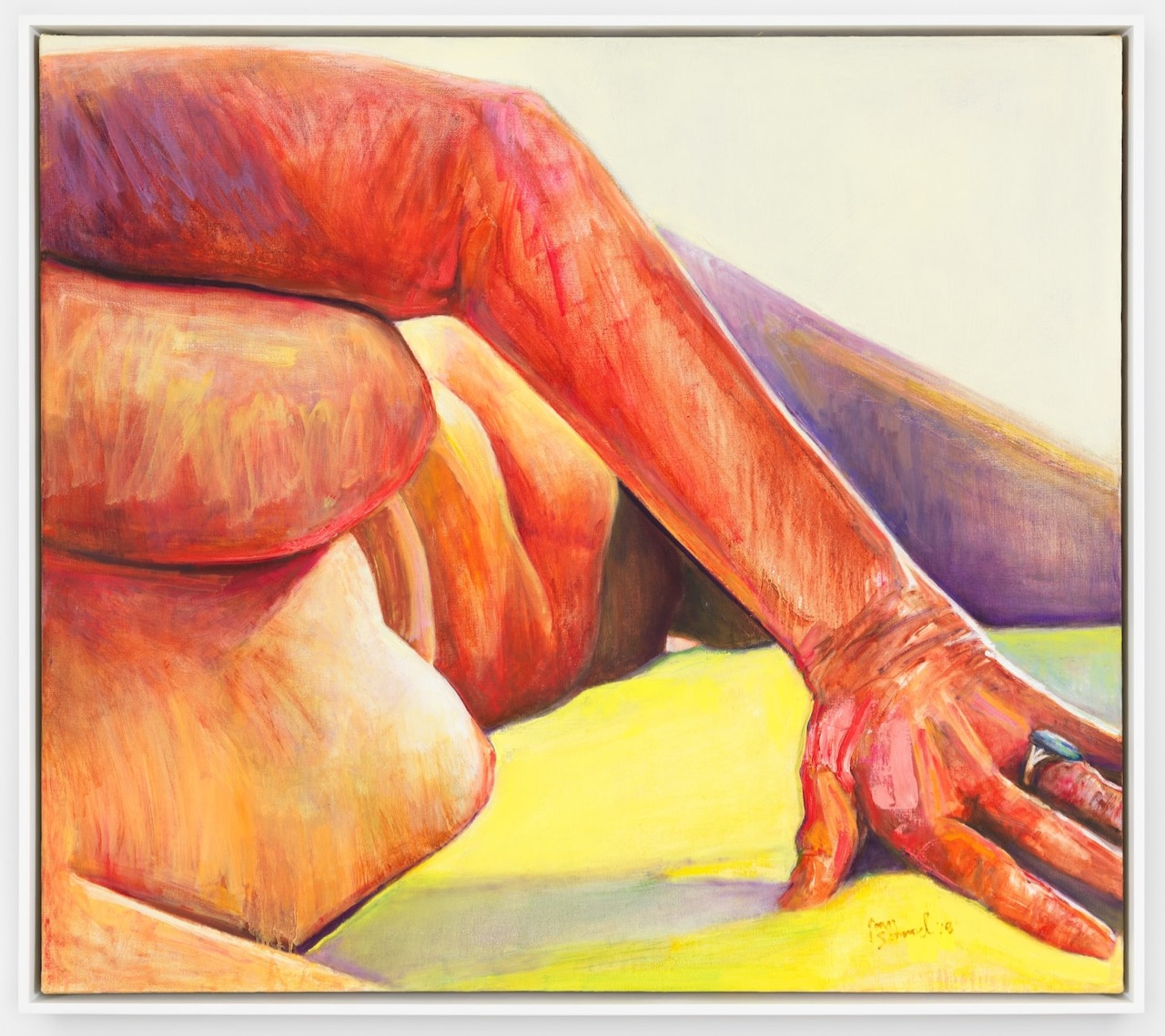

Joan Semmel, My Side, 2018. Oil on canvas, 44 × 50 inches. Image courtesy Alexander Gray Associates. © Joan Semmel / Artists Rights Society.

Semmel is often lauded for her continued frank depictions of herself, naked, undaunted by the prevailing culture’s rejection of old women’s bodies. As she should be. But, it should also be noted that a total absence of vanity, a ruthless dispassion regarding her own form, has been at the heart of her work all along. Even to call her career-spanning project self-portraiture feels a little off, as her interest in her “self” is as a symbol (the nude) and her attention to her evolving physical particularities seems driven more by a curiosity about their formal implications for her work than a desire to meditate on aging. Unromantically, ingeniously, she paints the woman who is conveniently always available at the studio, game to take off her clothes. She is the anti-muse.

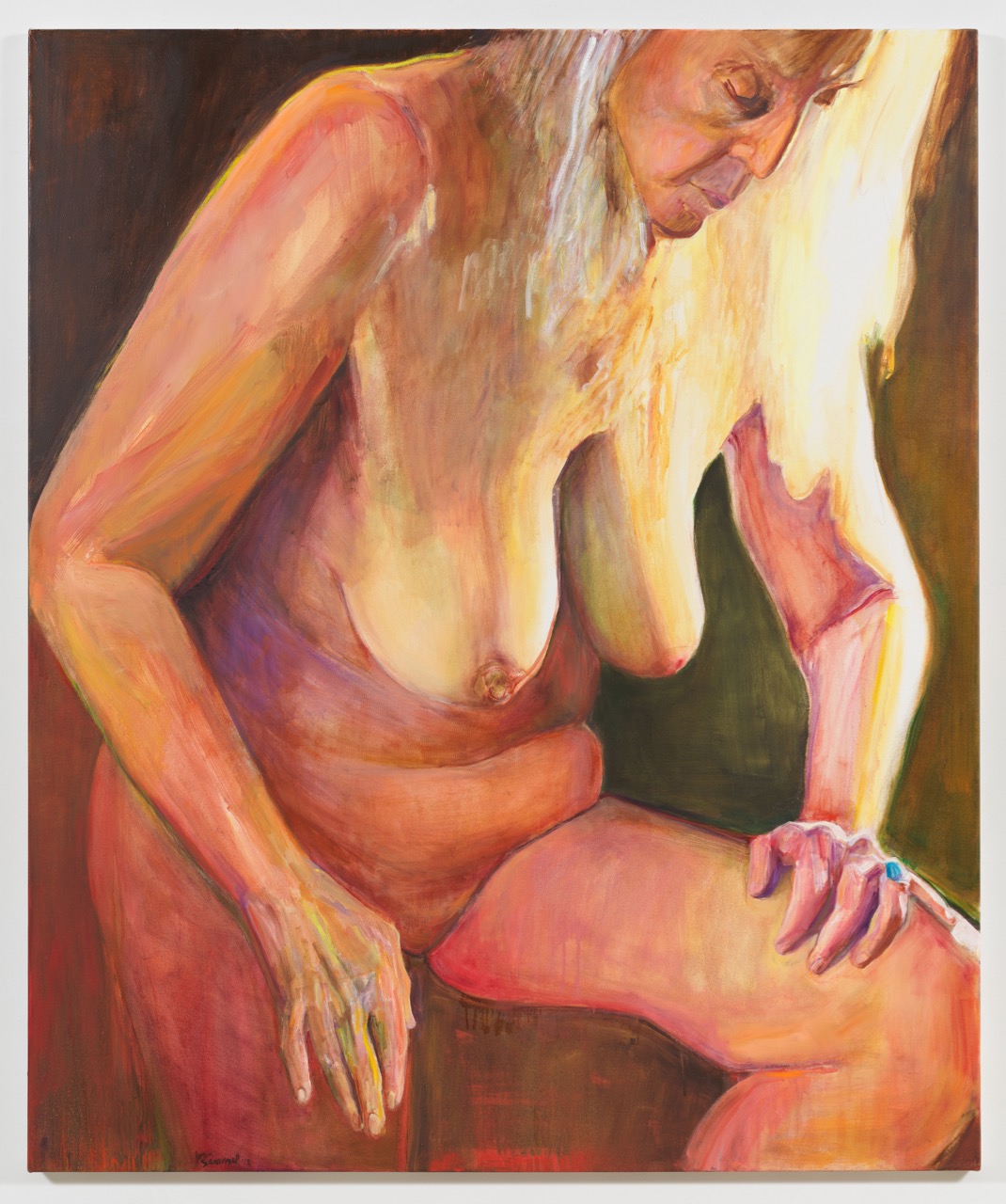

Joan Semmel, My Saskia, 2018. Oil on canvas, 72 × 60 inches. Image courtesy Alexander Gray Associates. © Joan Semmel / Artists Rights Society.

Thus, the moodlit My Saskia (2018)—an outlier in the seven-painting series that commands the big upstairs gallery—while too beautiful to laugh at, is a kind of joke, a good-natured flex. In the magnetic, loosely painted invocation of Rembrandt, Semmel’s figure sits downcast on a stool, leaning on her one raised knee. Emerging from the warm gloom, she’s partially illuminated by a piercing light that unites gray hair and hanging breasts in a jagged, then curvy, white-gold shape. Saskia van Uylenburgh was the Dutch master’s wife and sometimes model; Semmel’s titular Saskia is, of course, Joan Semmel. The canvas is the show’s most pointed reference to the art-historical baggage of figuration, a reminder that the artist’s five decades of collapsing and confusing gendered roles of looking, posing, and painting is not long at all considering what she’s up against. Each work can be seen as a “necessary elaboration,” the repetition of a small but winning gesture against a very old Goliath.

Joan Semmel, In the Green, 2017. Oil on canvas, 72 × 60 inches. Image courtesy Alexander Gray Associates. © Joan Semmel / Artists Rights Society.

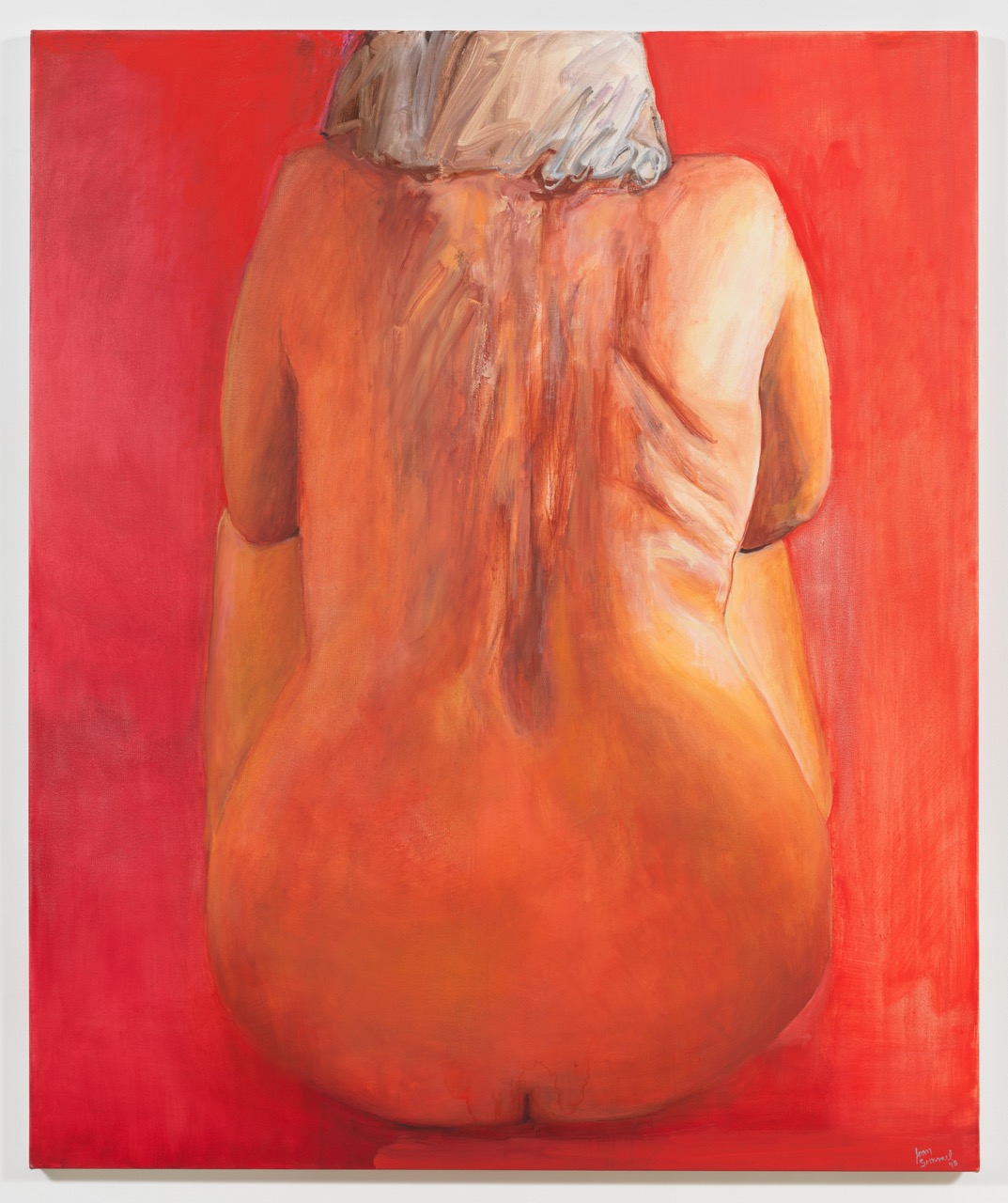

The overall effect is orgiastic rather than warlike, though. Semmel makes the sex appeal of her medium plain. She has worked in styles from abstract expressionism (in the 1960s) to sharp realism, here settling on an easy verisimilitude achieved with passionate gestural tangles and squirrely lines of electric pigment. In the Green (2017), painted with seductive fluidity, also features a sitting pose. The figure’s half-yellow, half-purple torso is twisted so that the line from head to knee is a bold diagonal, closing a bright green triangle of negative space. The jigsaw puzzle pieces of delirious color recall Semmel’s “fuck paintings” of the early 1970s (the series that preceded her self-portraits), whose vibrantly contrasting, coupled figures break up high-key background fields as they demonstrate, quite literally, what Semmel has called “the carnal nature of paint.” That same point is made rather differently in the voluptuous Seated in Red (2018), the show’s symmetrical, monochromatic wildcard. Seated on the ground with her knees up, back to us, the artist’s round, burnished bottom reflects the vermillion eternity surrounding her, while the scratchily rendered, sagging flesh of her upper back and the silver scribbles of her hair undercut the conventional woman-as-urn image.

Joan Semmel, Seated in Red, 2018. Oil on canvas, 72 × 60 inches. Image courtesy Alexander Gray Associates. © Joan Semmel / Artists Rights Society.

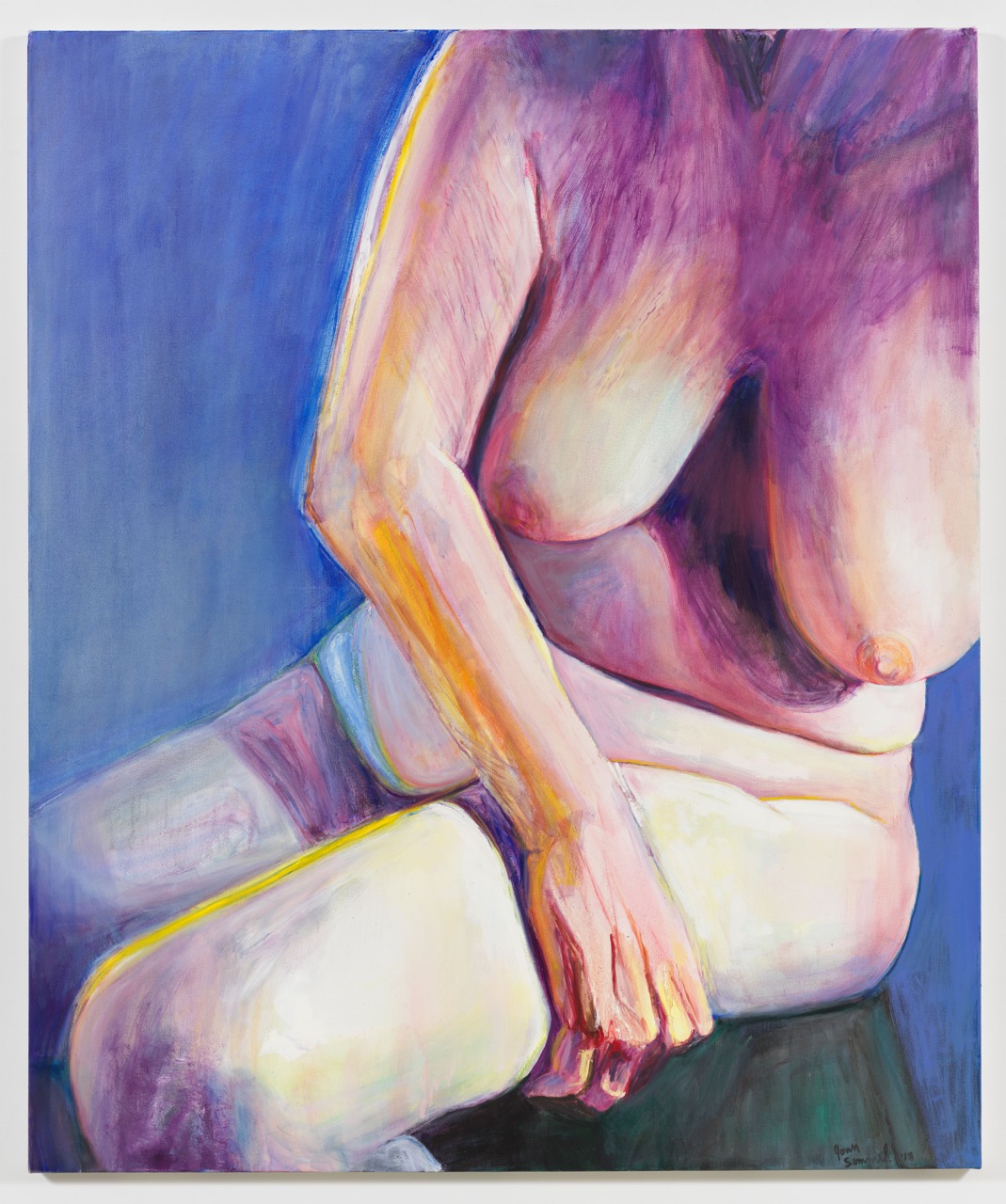

Big swaths of lush, unrestrained color structure the seven grand canvases upstairs—each a little smaller than a queen mattress—but the artist takes unmistakable pleasure in the details too. Turning (2018) boasts moments of psychedelic intensity. The back of the forearm that steadies her as she shifts her weight on a wooden stool is painted with gnarled vigor, like a red tree trunk streaked with purple, orange, and emerald green. Her elbow is a ringed burl. The waves of her hair appear iridescent, articulated delicately as individual locks of lavender, mustard, and celadon. Fleshed Out (2018) exists in a similar enchanted twilight of dark periwinkle. In it, Semmel’s glowing limbs are rimmed briskly with lines of bright yellow—a partial overlay reminiscent of past, layered compositions in which a silhouetted figure fragments a fully rendered one beneath to disorienting, exciting effect.

Joan Semmel, Fleshed Out, 2018. Oil on canvas, 72 × 60 inches. Image courtesy Alexander Gray Associates. © Joan Semmel / Artists Rights Society.

The painterly fireworks on view throughout this streamlined exhibition are the product of nearly every trick in Semmel’s book, pulled off simultaneously or in succession with quick, synthesizing ease. It’s a show of force that restates the consequential questions of representation that first announced her on the feminist-art scene. But, while the urgency of these issues has not waned, it seems the artist may nevertheless ultimately succeed in rolling that conversation into another one—about the thrills of her virtuosic craft and her importance as an influential figurative painter full stop.

Johanna Fateman is a writer and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She is coeditor of Last Days at Hot Slit: The Radical Feminism of Andrea Dworkin, forthcoming from Semiotext(e) on March 1, 2019. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a book.