Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Brainwave Music—a spontaneous improvisation between performers and their own minds.

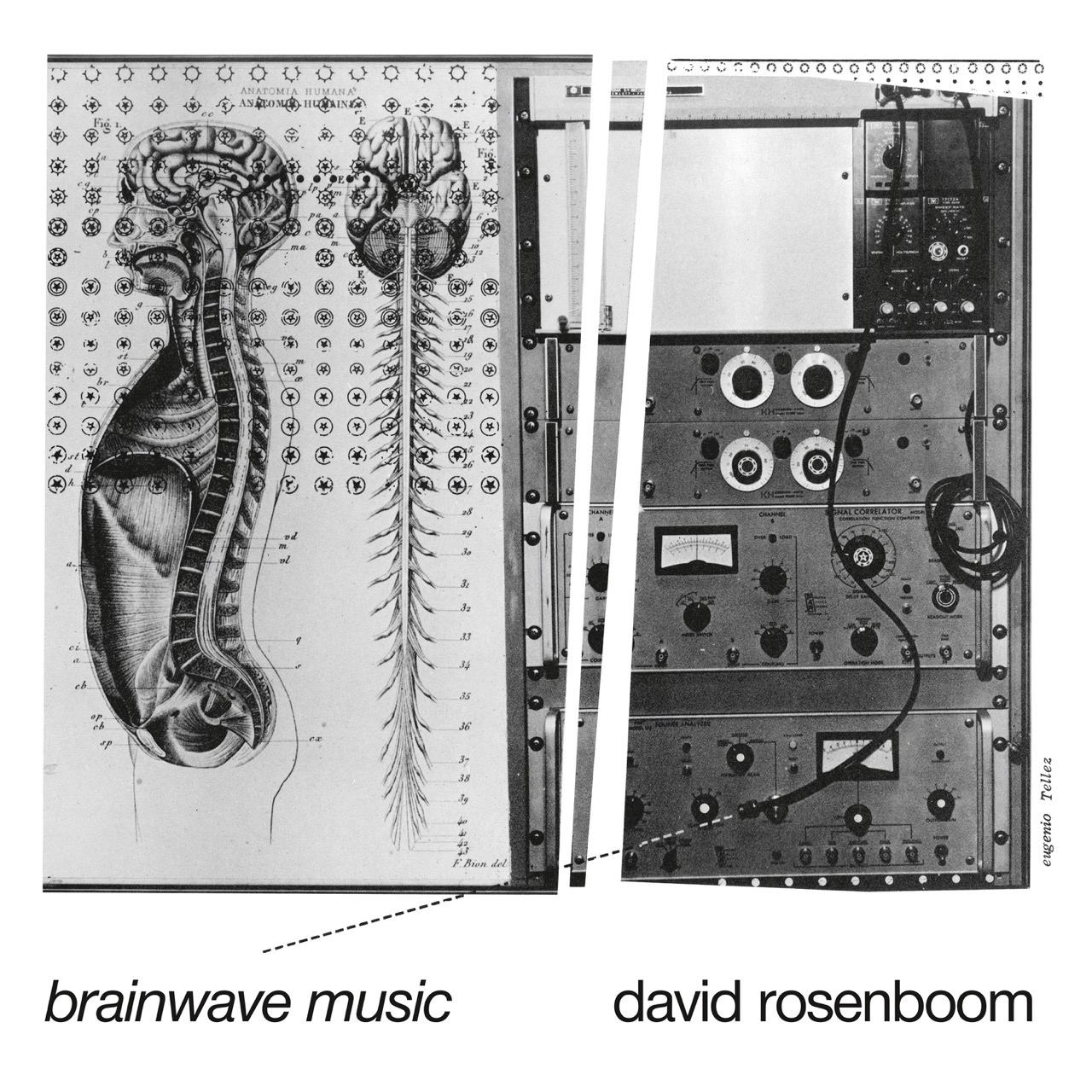

Brainwave Music, by David Rosenboom, Black Truffle

• • •

The technology of electroencephalography (EEG), which measures the activity of brainwaves, is now well known. These mysterious neural oscillations—alpha, beta, delta, gamma, theta—are part of the fabric of popular culture. Numerous iPhone apps and interfaces abound, claiming to deploy them to assist with everything from better sleep to sharper focus. Consumer-grade EEG headsets are used by gamers, meditation aficionados, and marketing firms. The related concept of biofeedback has made appearances in everything from science-fiction novels to self-help books and TV shows.

Technology has now progressed to the point where people can fly drones or drive sports cars by harnessing the power of their brainwaves. But some of the best artistic investigations using EEG were made in a slower, clunkier, more analog time. In 1934, physiologists realized that brainwaves could be converted to audio signals, paving the way for a generation of experimental musicians and composers to probe the potential of EEG devices. Alvin Lucier’s 1965 work Music for Solo Performer—in which he used his own alpha rhythms to control sounds in real time—is now considered to be a twentieth-century classic. The composer Richard Teitelbaum delved into biofeedback in several works, including his 1967 piece In Tune. John Cage and Pauline Oliveros were among the other composers to explore the field.

Many of the deepest and most sustained musical investigations of biofeedback have been conducted by the artist and composer David Rosenboom, who began working with sound in the 1960s. A new, deluxe, expanded double-vinyl reissue of his key 1975 record Brainwave Music is a revelation. The album still sounds forward-thinking, standing up as rich and compelling music. It can be enjoyed without knowing anything about the technical design, or the backstory of how it was made.

Still from video made by Western Front, Vancouver, of David Rosenboom performing “On Being Invisible” there on February 28, 1977. Image courtesy Black Truffle.

The expansive opening track, “Portable Gold and Philosophers’ Stones,” has a meditative, peaceful quality. Soft melodies unfold over a warm bed of drones, similar to the ones produced by the tanpura, an Indian instrument. “Piano Etude I (Alpha)” is reminiscent of the New York minimalist music that was in vogue at the time, put forth by Philip Glass and others—a nervy, insistent piano figure, quickly repeating. The twist here is that we’re hearing the piano as subtly processed by filters controlled by the brainwaves of the performer (in this case, Rosenboom’s). The bonus track on this release, a sprawling forty-minute live performance of “On Being Invisible,” performed by Rosenboom at the Western Front in Vancouver in 1977, starts out placid and soothing, before erupting into a riot of sounds ricocheting wildly from all sides. A fuzzy still image from the show depicts a shaggy-haired, bearded Rosenboom with electrodes shooting out of his head, wielding an early minicomputer, the unique electronic instrument known as the Buchla music easel, and other gear. 1977 may have been the year punk broke, but this was more radical: imagine a symphony of twanging rubber bands, frantic electrical zaps, and chaotic bleeps of Atari videogame battles counterbalanced with the calm drones and silky swoops and glides of an Indian raga. Somehow it all works together, growing weirder and more enthralling with each passing minute.

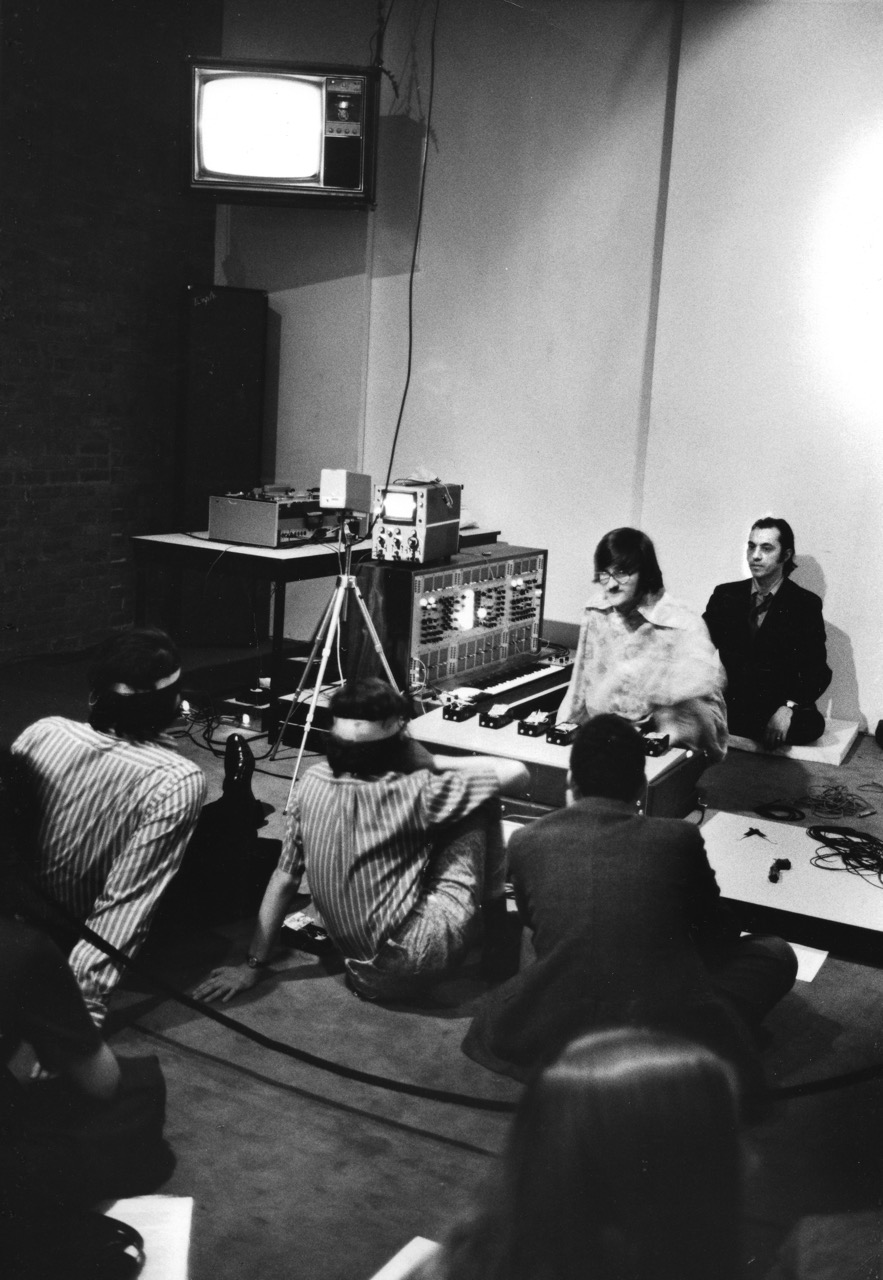

Image from David Rosenboom’s installation and performance event Ecology of the Skin at Automation House in New York in 1970, which included brainwave music performances, brainwave music audience participation, visual phosphene stimulation stations, and information presentations. Photo: Peter Moore. Image courtesy Black Truffle.

All of Brainwave Music was created using biofeedback. A small group of people wearing electrodes (“active imaginative listener-performers,” to use Rosenboom’s terminology) generated data, which, with further filtering and processing, generated music. Feedback from their EEG readings, and measurements of body temperature and galvanic skin response, among other things, influenced the path of the music. The composition morphed and evolved along with the performance—a kind of spontaneous improvisation between the performers and their own minds, in combination with Rosenboom’s processing and framework to give it structure and depth (one can imagine how these experiments could come across as incoherent noodling in the wrong hands). The scores of these pieces resemble block diagrams or circuit schematics more than they do standard sheet music—much like the scores of the late David Tudor, a key pianist and interpreter of John Cage’s works who later became a wildly inventive composer of his own live electronic music. In a way, you could look at an EEG machine as a sort of early electronic instrument—one that promoted an interactive approach to making music through its unique interface. You could also envision it as part of a cybernetic system; like Brian Eno and others who came of age in the 1960s and 1970s, Rosenboom was fascinated by the potential of cybernetics as applied to music.

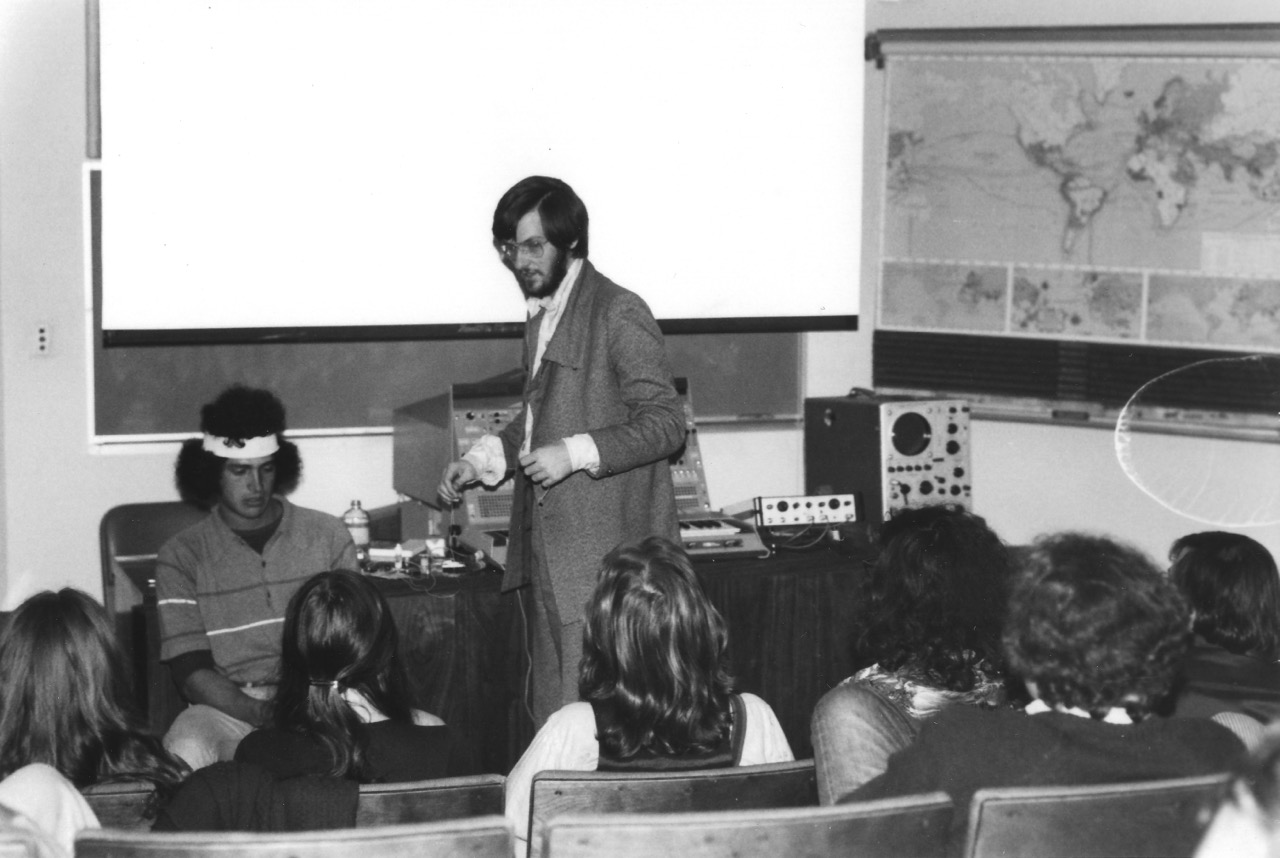

David Rosenboom giving a demonstration of biomusic at Mills College in 1971. Photographer unknown. Image courtesy Black Truffle.

Rosenboom’s early writings speak to the cyber-utopian dreams of the era. His prescient 1975 book Biofeedback and the Arts was written at a time when the personal computer revolution was in its infancy. “Through the use of computers as appendages of man’s brain and methods of learning with biofeedback,” he predicted, “rates of information processing will be achieved that approach the speed of light . . . life will eventually be embodied in information-energy networks creating nonphysical art; spiritual art will be revived as established networks connect us firmly.”

But there was a deeper philosophical impulse, too. As he told the composer Larry Polansky in a 1983 interview in Computer Music Journal, “I saw the idea of monitoring the brain state of an individual, and making that audible, and making that something that organizes musical form, as a model for the notion that humanity must evolve in order to survive itself and what it’s doing to Earth.” Brainwave Music introduces us once again to that optimistic vision for connecting music both to the outer world, and our inner worlds—the endlessly shifting landscapes inside our heads.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including The Guardian, Wired, The Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.