Mark Polizzotti

Mark Polizzotti

A new biography of blues legend Robert Johnson.

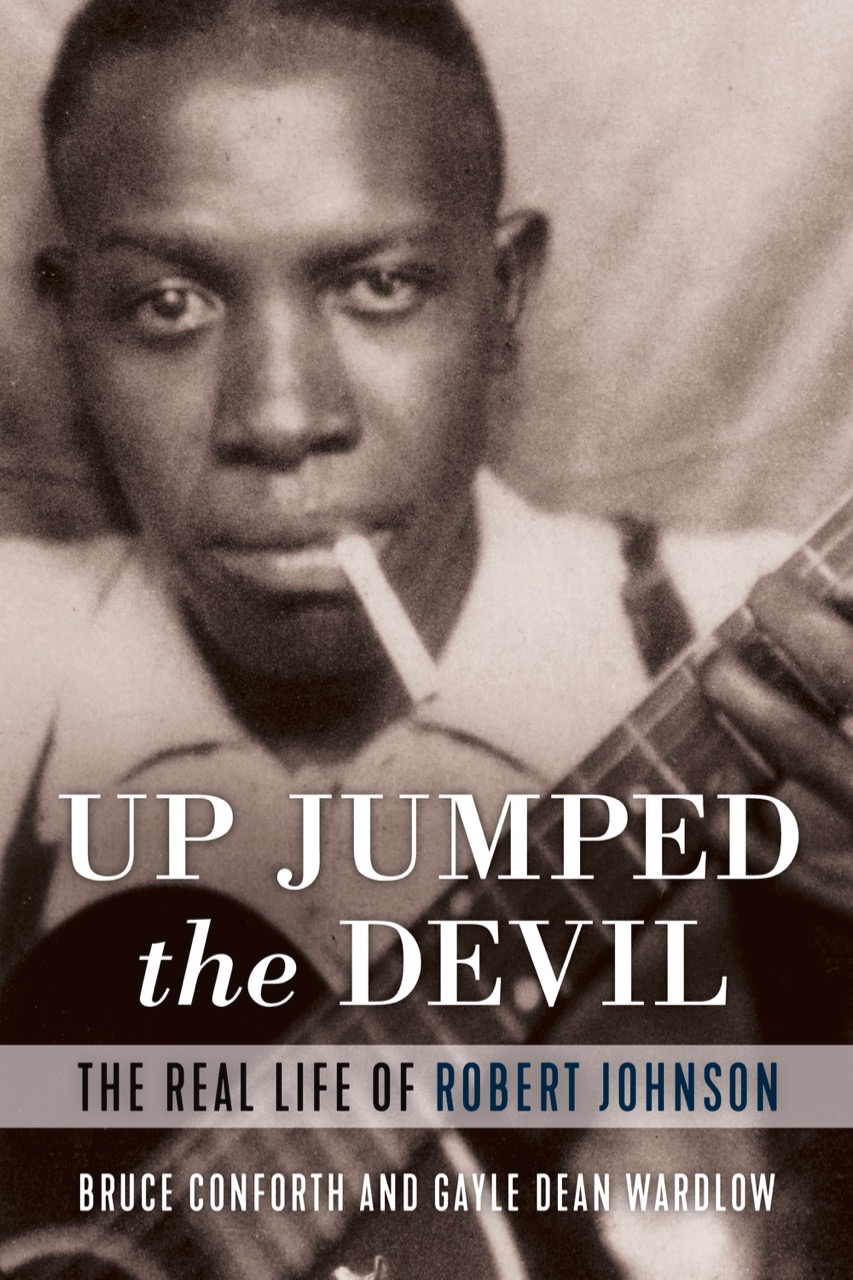

Up Jumped the Devil: The Real Life of Robert Johnson, by Bruce Conforth and Gayle Dean Wardlow, Chicago Review Press, 326 pages, $30

• • •

Few artists have been as draped in mystery as blues wizard Robert Johnson. The more people searched for him, it seemed, the more the enigma deepened. Legends about him were handed down and burnished: that he sprouted sui generis from somewhere in the Delta; that he was poisoned (or shot, or stabbed) by a jealous husband (or wife, or girlfriend); and—the most tenacious of all—that he gained his celebrated musical prowess by selling his soul to the devil at the crossroads one dark midnight.

In fact, so much haze surrounds Johnson’s life, music, and person that the mythmaking has itself become part of the myth. As early as 1938, the year of his death at age twenty-seven (making him a charter member of a heavily romanticized “27 Club” that includes the likes of Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, and Kurt Cobain), the tale began spreading that he’d been murdered mere days before producer John Hammond could nab him for his legendary “From Spirituals to Swing” concert at Carnegie Hall (he had in fact died months earlier). In the years that followed, blues historians and musicians who had known Johnson added further, sometimes blurred, touches to the murky portrait, which were duly disputed by other historians and musicians. Even the two most dogged scholars of Johnson’s life and music, folklorists Mack McCormick and Steven C. LaVere, became mired in partisan rivalries, and both died before publishing many of their key discoveries; McCormick’s long-promised Biography of a Phantom tantalized aficionados for some forty years before finally never happening.

The music writer Peter Guralnick, who authored one of the first comprehensive essays about Johnson (“Searching for Robert Johnson,” 1982), noted that any knowledge of the man’s artistic lineage “seems strangely beside the point to me when compared to the unabashedly apocalyptic effect of the music.” Personally, I find it fascinating to ponder where Johnson’s prodigious aptitude as a copycat crosses the line into fierce originality, but I take Guralnick’s point. Neither wholly original nor overtly arresting on first listen, Johnson’s music nonetheless has a quality, ineffable and gripping, that sets it apart from the work of his contemporaries, even those he most closely emulated. If you’re receptive, it can strike to the heart and the bone, as it apparently did the many audiences in his passway. For those of my generation, who discovered Johnson through the 1961 and 1970 Columbia Records reissues, the songs and the riddles surrounding them were indissociable. We didn’t just listen to Robert Johnson, we ate, slept, and breathed him. His recordings carried the menacing seduction of a time out of time, a dark, impenetrable 1930s that seemed to exist only at night. The mystery fueled the thrill.

Which is why Up Jumped the Devil is at once welcome and unnerving. A clear-eyed assessment of Johnson’s life and career—starting with the fact that it was a career, not some demonic compact—it aims to strip away, like old varnish, the many layers of inaccuracy and romanticizing that have accreted over the decades. Authors Bruce Conforth and Gayle Dean Wardlow have, by their own reckoning, spent more than fifty years researching their subject and they want no truck with perpetuating mysteries, thrilling or otherwise. Regarding, for instance, Johnson’s supposed barter for mastery of the “devil’s music,” one of the main pillars supporting his myth, they are categorical: no hoodoo involved, just hard work, a good teacher, and loads of talent. Period.

Granted, this is not exactly news to those who have absorbed documentaries such as The Search for Robert Johnson (Chris Hunt, 1992) or Can’t You Hear the Wind Howl? (Peter Meyer, 1997), or books like Elijah Wald’s Escaping the Delta (2004) and Tom Graves’s 2008 mini-biography, Crossroads: The Life and Afterlife of Blues Legend Robert Johnson. One of the biggest surprises of Up Jumped the Devil, in fact, is that there are so few surprises. But that’s no reason to ignore it, for what Conforth and Wardlow do provide, for the first time, is the connective tissue that had been lacking between the established episodes, giving them greater depth and context. Having mined census records, school records, period maps, and birth and marriage certificates, in addition to reading widely, conducting numerous interviews, and drawing on their predecessors’ unpublished insights, they offer much to satisfy the cognoscenti. Among the book’s virtues are the most complete picture to date of Johnson’s childhood and early years, including many new details about his time in Memphis; a nuanced account of his interpersonal relationships—with family, with fellow musicians, with women; and a resonant portrait of the life of an itinerant musician, its freedoms and its fug. This last aspect I found especially moving, for while it’s well known that Johnson spent most of his professional life on the road, this book lets you feel it—the filthy boxcars, provisional lodgings, ever-changing venues, and fleeting moments of human contact.

They also, finally, get to the bottom, or as close as one can, of what happened that night in August 1938 when Robert Johnson met his fate. The second and most controversial pillar of the myth, Johnson’s death has as many versions as there are witnesses to tell them. The most commonly accepted account is that he was given poisoned whiskey by a jealous husband while playing a juke joint—a “casual killing” that barely registered at the time. I won’t reveal the details here of what actually happened: having done some remarkable detective work to establish the facts, Conforth and Wardlow have earned that privilege. Let’s just say that the full story is even sadder than we knew.

We can only speculate on what Johnson would have become if he hadn’t died prematurely, if he’d enjoyed a longer recording career and lived to see the blues revival of the 1960s. Would he still occupy the same place in music history and in our imaginations? It’s an open question. Thanks to Conforth and Wardlow, we now know as many of the straight facts about Johnson’s time on earth as we’re likely to. What’s harder to gauge is whether demythologizing the life also skims some of the mystery, thrill, and apocalyptic effect from the music.

Mark Polizzotti’s books include Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995; revised ed. 2009), Bob Dylan: Highway 61 Revisited (Bloomsbury, 2006), and Sympathy for the Traitor: A Translation Manifesto (MIT Press, 2018). He has translated over fifty books from the French, including works by Patrick Modiano, Gustave Flaubert, and Marguerite Duras, and his essays and reviews have appeared in the New York Times, New Republic, Bookforum, Wall Street Journal, The Nation, Parnassus, and elsewhere. He directs the publications program at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.