Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

The composer-musician’s Organic Music Theatre is a marvel

archival release.

Eagle-Eye Cherry and Don Cherry in Gamla Stan, Stockholm, ca. 1973. Courtesy Keith and Ingrid Knox. Photo: Rita Knox.

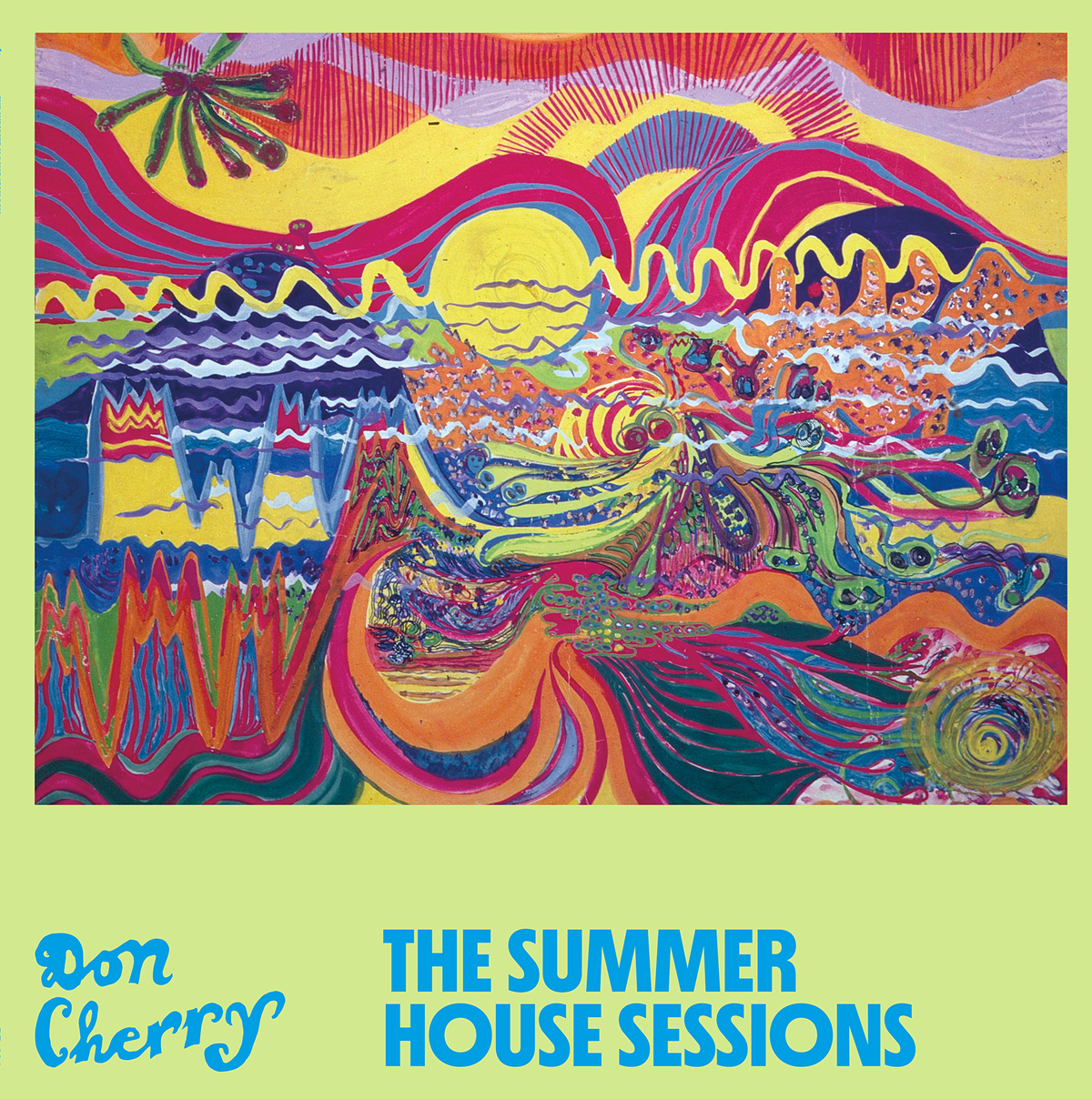

The Summer House Sessions, by Don Cherry, and Organic Music Theatre: Festival de jazz de Chateauvillon 1972, by Don Cherry’s New Researches, Blank Forms

• • •

Don Cherry was one of the great composers and multi-instrumentalists of the twentieth century, an innovator in jazz and in pan-sonic explorations that moved beyond fusion to a total transcendental synthesis. He and his wife, the Swedish artist and designer Moki Cherry, created rich atmospheres and communal performances that merged art, sound, and the simple joys of domestic living.

Cherry was born in Oklahoma City in 1936 to an African American father and a Choctaw mother. He moved to Los Angeles in 1940, to the Watts neighborhood on the south side of the city. In his early twenties, he joined Ornette Coleman’s pioneering group, playing on many classic albums—including The Shape of Jazz to Come (1959), Tomorrow Is the Question! (1959), Change of the Century (1960), This Is Our Music (1961), and Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation (1961). Cherry also recorded with Albert Ayler, performing on legendary albums such as Ghosts (1965) and New York Eye and Ear Control (1965), and appeared on records alongside many other icons of modern jazz, including John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Carla Bley, Charlie Haden, Steve Lacy, and Sun Ra.

By the 1970s, Cherry had built up a tremendous reputation in jazz, but he was restless in his studies of other forms of music from around the world. At a young age, he’d become enraptured by shortwave radio, flicking through mysterious music broadcasts from faraway lands. In his thirties, he made a new home in a remote village in Sweden. It wasn’t entirely by choice—in the late 1960s, he and Moki attempted to settle in upstate New York, but racism kept the couple unable to buy a house. They landed in 1970 in Moki’s native Sweden, where they bought an abandoned schoolhouse in the tiny southern town of Tågarp for $4,000, converting it into a unique living space that became a home base for their travels and myriad musical investigations.

Gathering at Tågarp Schoolhouse, ca. 1973. Courtesy Keith and Ingrid Knox.

Blank Forms in New York recently mounted an impressive, multilevel retrospective of the pair’s work, including a small and colorful exhibition in Brooklyn of Moki’s tapestries, paintings, posters, and other ephemera; two newly issued albums of archival recordings from the late 1960s and early 1970s; and a 496-page book, Organic Music Societies, collecting numerous essays, interviews, and color photographs. All of these projects are vital, with the minor quibble that the book’s design, with its nonstandard margins and tight spacing, is difficult to read for those with disabilities like dyslexia and people with eye problems.

The first of those reissued albums is The Summer House Sessions, starring Cherry and several Swedish jazz musicians, originally recorded in 1968 in a house in Kummelnäs, outside Stockholm. The later Organic Music Theatre: Festival de jazz de Chateauvallon 1972 showcases a performance in the south of France featuring Don Cherry, the noted Brazilian percussionist Naná Vasconcelos, Moki Cherry, a puppet troupe, and several others. Both are remarkable documents of transitional points in Don Cherry’s musical development. The Summer House Sessions is still recognizable as jazz—a riotous, intense improvisational ride incorporating musicians from all over the map. But Organic Music Theatre goes beyond jazz into something else entirely—an ecstatic, openhearted melding of cultures. It is the first live recording of Don and Moki’s “organic music” concept, a holistic blend of the arts and education. It is an album that everyone should own, an absolute marvel.

The record sports a unique lineup, to be sure, involving a global assortment of instruments and performers. Don Cherry plays piano, harmonium, and tanpura, and also sings; Naná Vasconcelos performs with a single-string instrument called a berimbau and other percussion; Swedish musician Christer Bothén plays a Malian guitar called a ngoni along with additional piano and percussion; French musician Doudou Gouirand provides saxophone and percussion; Moki Cherry contributes more tanpura and vocals, along with elaborate, psychedelic, hand-sewn set design. Another notable addition to the concert was Annie Hedvard and her Danish troupe Det Lilla Cirkus, who created a puppet show.

Don Cherry, Moki Cherry, and Christer Bothén hosting a children’s workshop, location unknown, ca. 1973. Courtesy the Cherry Archive, the estate of Moki Cherry.

It would seem that a live performance by such a motley roster would be all over the place, but the album is incredibly catchy and listenable —you could easily imagine your parents liking it, or putting it on at a dinner party, or listening to it in the car. For me, the music also strikes a personal chord, reminding me powerfully of my childhood. Organic Music Theatre is full of musical themes familiar to anyone who studied Indian music. Growing up, I played harmonium and piano, jamming with my dad, a tabla player and singer. Indian tapestries filled the walls, and I wore bright clothes made by my grandparents, an echo of Moki’s hand-stitched multicolored world.

Moki Cherry and Don Cherry with Gianpiero Pramiaggore (seated next to Don on right), ca. 1975. Courtesy the Cherry Archive, the estate of Moki Cherry.

Cherry’s music brings me back to that time, beginning with the very first tune, “Intro: Dha Dhin Na, Dha Tin Na”—a theka, a kind of rhythm from Indian classical music. Further into the album, the familiar “sa-re-ga-ma-pa-dha-ni-sa” syllables (the notes of the octave in Indian music) surface, along with the repetition of well-known Sanskrit phrases like “Om Shanti.” Cherry’s piano lines are slow and patient; he comes across as the world’s coolest elementary school teacher leading the students in a singalong. A standout is the song “Ganesh,” a sweet piano tune with Don singing parts of the maha-mantra mixed in with English. In an alternate universe, with glitzy production, you could imagine some of these songs being big pop hits, like “My Sweet Lord” was for George Harrison.

Bobo Stenson (seated on far left), Jan Robertson (cello), Christer Bothén (sax), Eagle-Eye Cherry (seated in foreground); bottom row: Don Cherry (horn), Palle Danielsson (bass), Moki Cherry (tanpura). Courtesy the Cherry Archive, the estate of Moki Cherry.

The album maintains a warm, wholesome feeling throughout. Don and Moki Cherry’s vision for an “organic music theatre” is a beautiful one—a cross-cultural, homespun, communal project that transcends the ordinary bounds of capitalism and commerce. The unearthing of this recording is an extraordinary gift—one we are all lucky to hear.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.