Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

From embellished caftans to “magnificent asses”: the Drawing Center explores the work of the Lebanese artist.

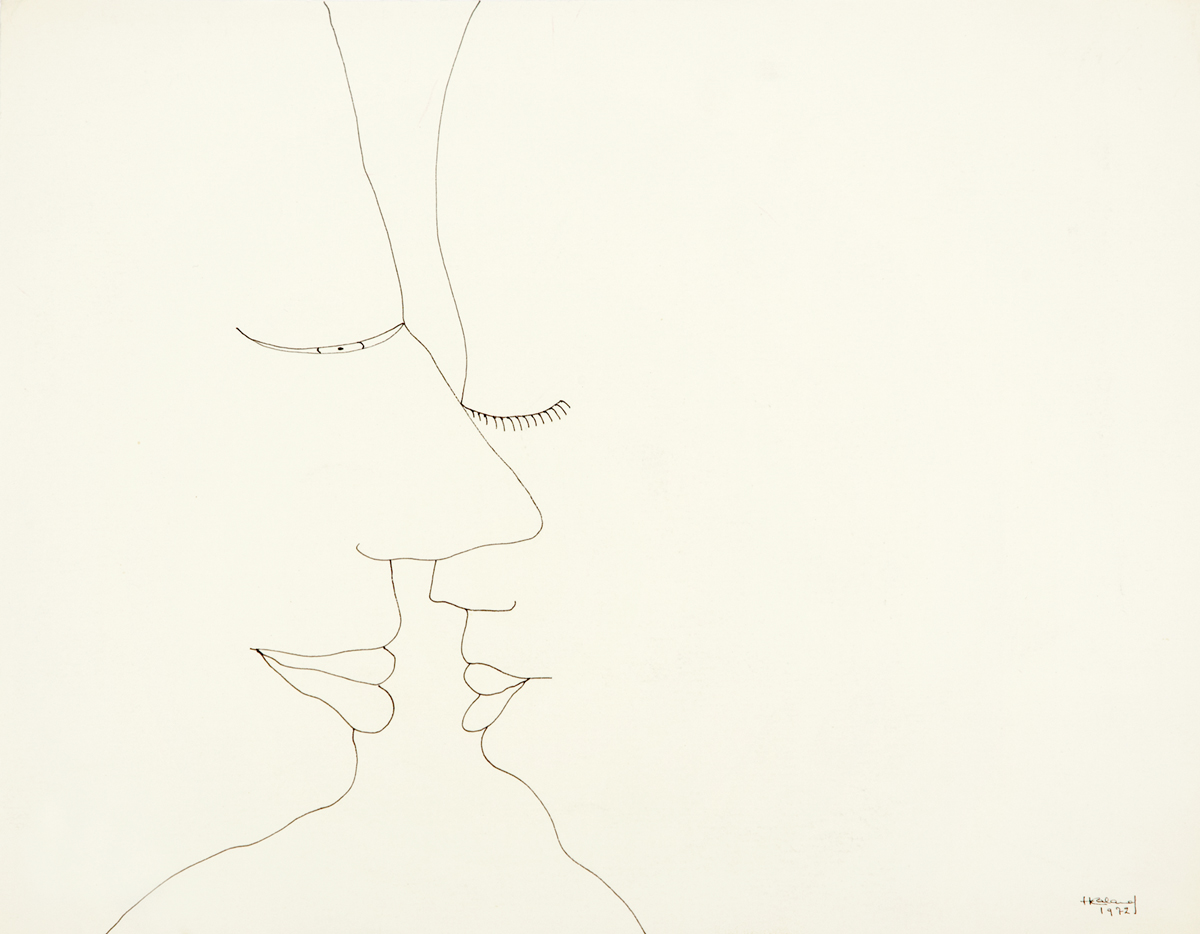

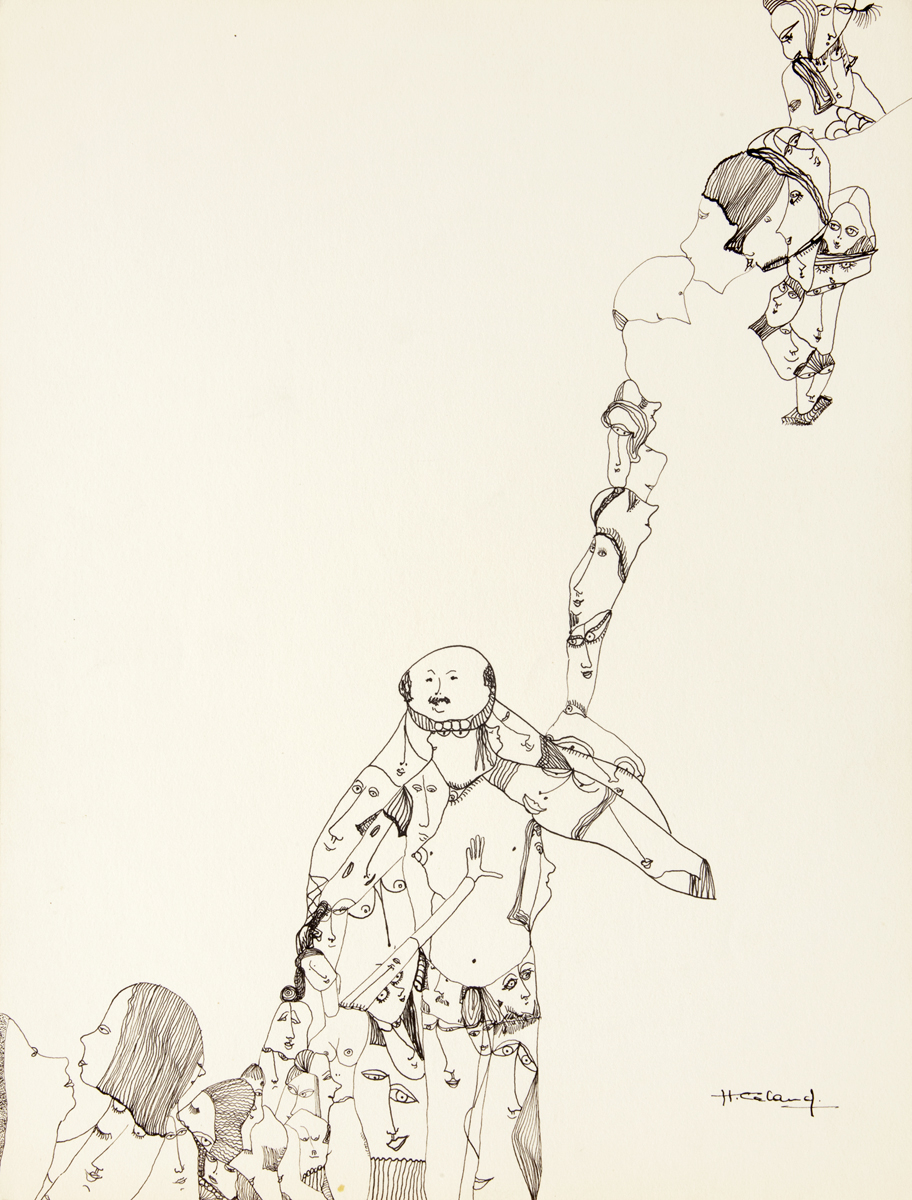

Huguette Caland, Bouches (Mouths), 1972. Ink on paper, 10 1/2 × 13 3/4 inches. Courtesy the Drawing Center.

Huguette Caland: Tête-à-Tête, curated by Claire Gilman with Isabella Kapur, the Drawing Center, 35 Wooster Street, New York City, through September 19, 2021

• • •

The story of Huguette Caland’s breakthrough sounds totally credible but suspiciously familiar. According to it, Caland emerged from obscurity only in the later years of her life, when the world finally took note of her formidable erotic drawings and outrageously biomorphic abstract paintings, and she was at last recognized as an artist of merit. Similar narratives have formed in recent years around the work of Carmen Herrera, Zarina Hashmi, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, and Caland’s two great Lebanese compatriots, Etel Adnan and Saloua Raouda Choucair. Each case involves a woman, usually a woman who comes from somewhere outside of Europe or the United States. For all the good canon-busting work these stories do—lending fresh energy to establishment institutions, generating waves of new scholarship—they also tend to raise the same set of meddlesome questions: To whom was the artist so obscure in the first place, where has she now been recognized, and what does her breakthrough really mean in relation to her work?

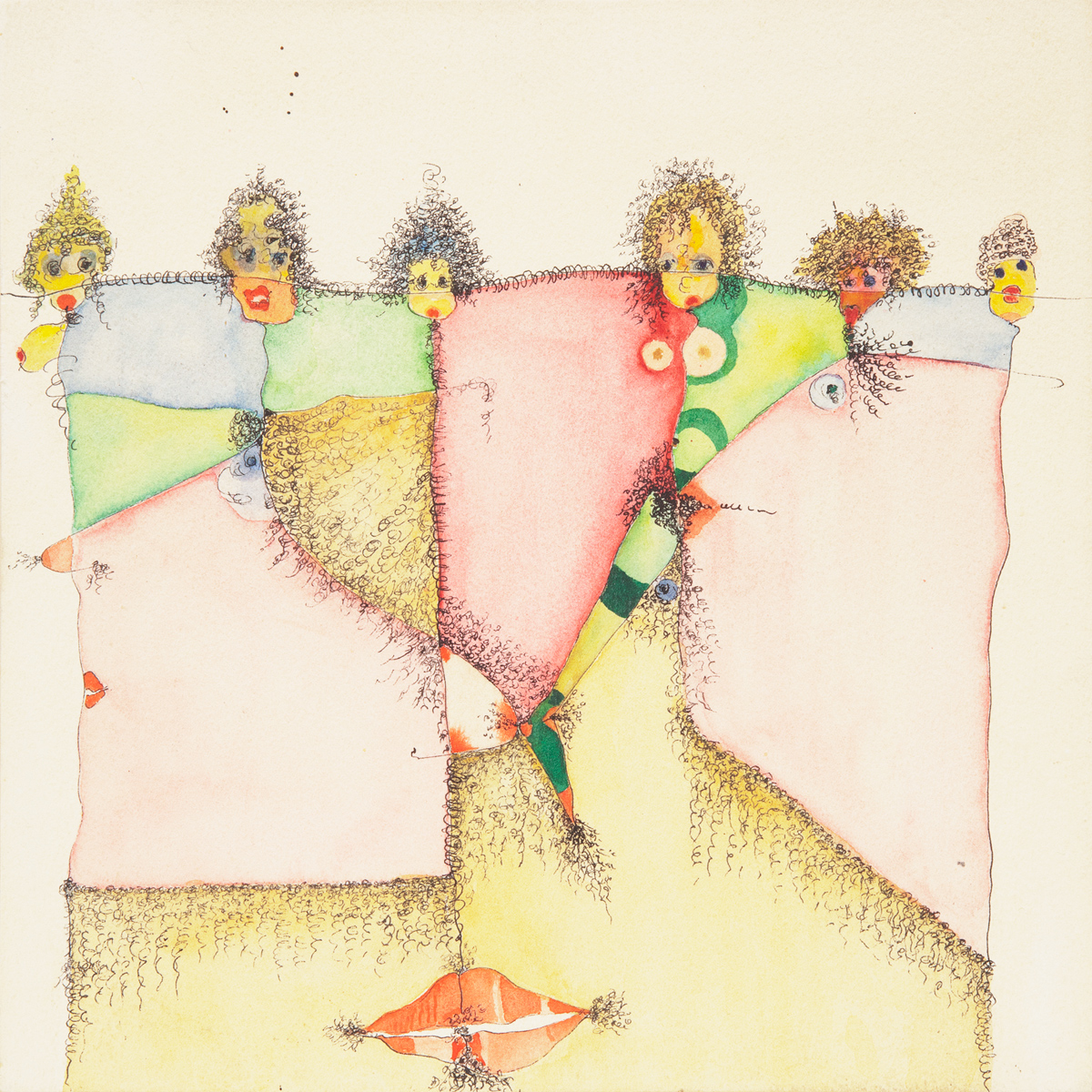

Huguette Caland, Homage to Pubic Hair, 1992. Mixed media on paper mounted on panel, 10 × 10 inches. Courtesy the Drawing Center.

Caland, it must be said, was never unknown in Lebanon. She was effectively born a public figure. During the time of the French mandate, when the former Ottoman provinces of Lebanon and Syria were caught up in colonization, Caland’s father, Bechara El-Khoury, served numerous terms as a member of parliament, cabinet minister, and prime minister. When Caland was twelve, he was imprisoned for his part in fighting off the yoke of France. Then, for nearly a decade, he was Lebanon’s first post-independence president. As a teenager raised in a prominent family known to this day for prizing high achievement, Caland was looking for the thing to distinguish her. She studied piano, then abandoned it for painting under the tutelage of an Italian teacher, Fernando Manetti, who specialized in frescoes. Like her father with resistance, Caland’s thing turned out to be rebellion—a total rejection of her privilege, and an absolute refusal to accept the double standard forced upon women of her generation: they were liberated by the progressive politics of their era but restrained by their families and a dispiriting social milieu, which expected good, morally pure, and extremely circumscribed behavior above all else. In her art, Caland, who passed away two years ago at the age of eighty-eight, oscillated wildly (and wonderfully) between saying way too much in her paintings—about her body, her lovers, pleasure, and the fickle ways of the world—and using her drawings to quiet her mind and keep her mouth shut.

Huguette Caland: Tête-à-Tête, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna.

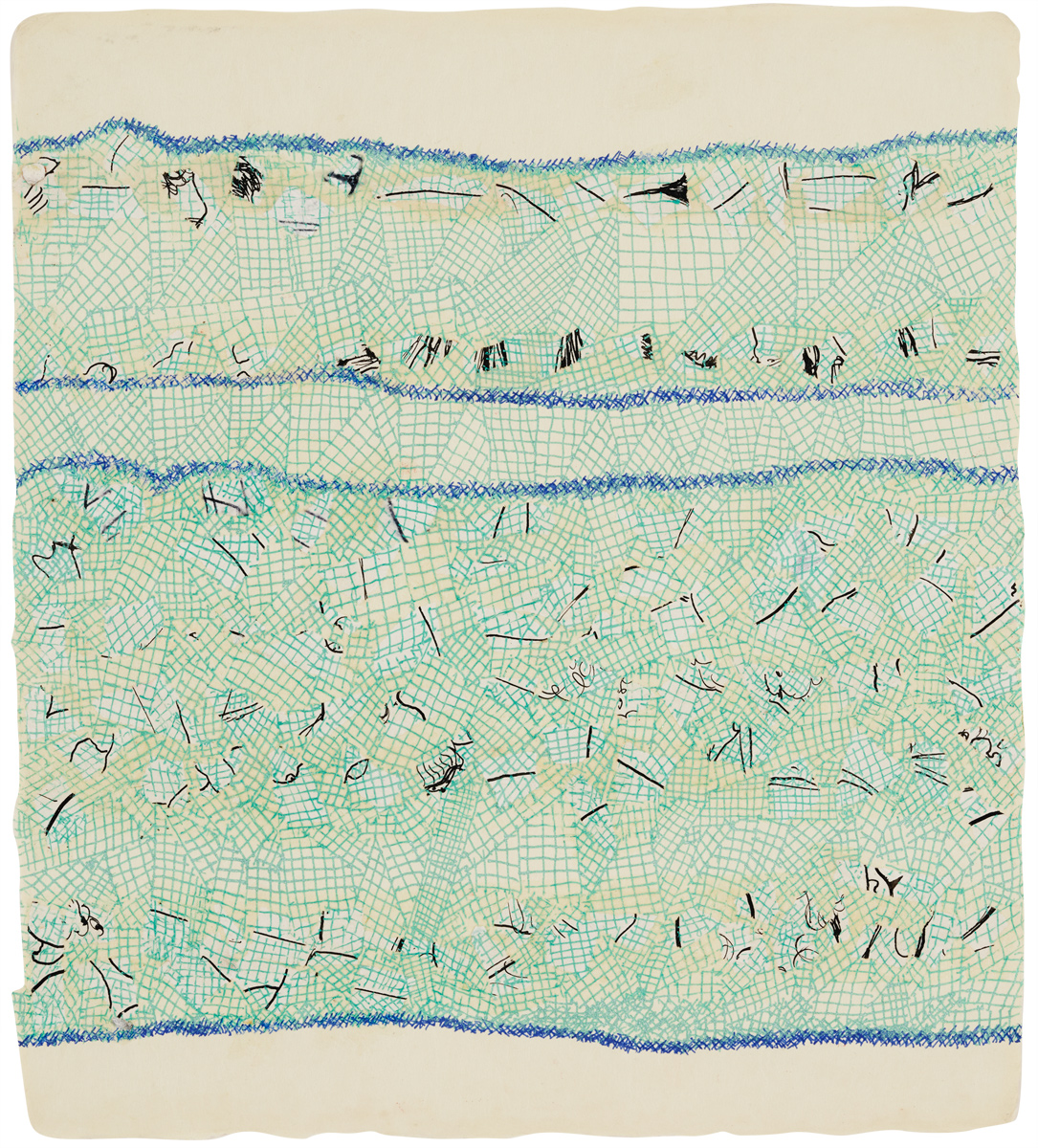

The singular and impressive contribution of the Drawing Center’s current exhibition Huguette Caland: Tête-à-Tête is that it hears the way liberation and restraint echo throughout the artist’s work and life and turns them into a generative theory for reading the drawings, paintings, sketchbooks, diminutive terra-cotta sculptures, and riotously embellished caftans on view. Organized by Claire Gilman with Isabella Kapur, the show feels intimate but includes over a hundred pieces and follows nearly every twist and turn in the artist’s complex oeuvre. One enters the space between two key works in black and white. On one side is Caland’s early portrait of Helen Khal, from 1967, showing only a bent knee and a pointed breast against a decorative background. Tender and sexy, the oil-on-linen painting pays tribute to a friend, teacher, and fellow artist with whom Caland once shared a studio. On the other side is a tremendous example of Caland’s later “Silent Letters” series, Untitled, from 1999, composed of neat, interlocking blocks of thick lines, thin lines, and wide-open spaces, Caland’s pen fading from density to oblivion like a problem solved by a Zen koan.

Huguette Caland, Untitled, 1999. Mixed media on paper, 11 × 9 3/4 inches. Courtesy the Drawing Center.

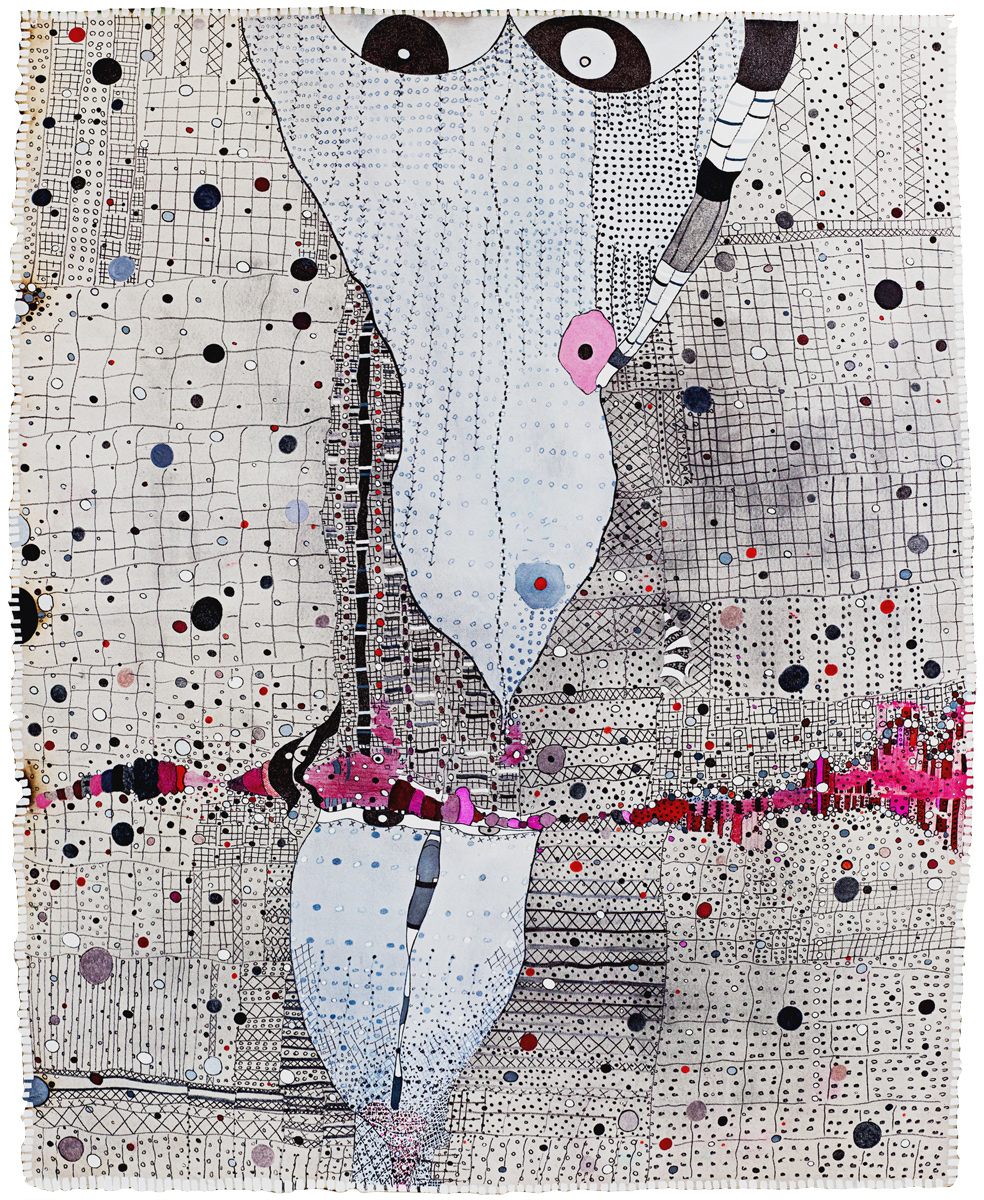

From there, Tête-à-Tête proceeds carefully, judiciously, with only scattered intensities of color, through Caland’s spare line drawings and her funny caftans adorned with amorous hands and pubic hair to her most famous “Bribes de corps” paintings, which suggest huge posteriors and cavernous crevices and other such erogenous body parts mashed together. Only when turning the corner into the far gallery does one come up against the lush color of Caland’s late work in her obsessive, almost mural-sized evocations of cities and her equally exuberant “Rossinante Under Cover” series based on Don Quixote’s horse.

Huguette Caland, Rossinante Under Cover XII, 2011. Mixed media on canvas, 52 × 41 inches. Courtesy the Drawing Center.

Caland’s rebellions were many. She notoriously married a Frenchman, a scandal for the family of a nationalist hero. Her husband took a mistress. She was very public with her own adulteries. She jettisoned high fashion to dress in formless caftans, another scandal. But then her father fell ill, and she nursed him through cancer until his death in 1964. That year, at the age of thirty-three, she turned to painting with an enormous, monochromatic red sun representing the sickness she had seen. Trained as a lawyer, the mother of three small children, she went back to school to study art. In 1970, she declared at a dinner party that she was leaving her family to pursue her vocation in Paris, without them. After arriving in France, she embarked on a long, powerful affair with the Romanian sculptor George Apostu. When he died, Caland moved to California and stayed there for nearly three decades.

Huguette Caland: Tête-à-Tête, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna.

A compelling alternative to the breakthrough narrative, in Caland’s case, is the story of her release from Lebanon—from the abundant corruptions of a failed political project and from the palpable limitations of a nationally construed art history—and her return to embrace it, nostalgically, at the end of her life, when she moved back in 2013 to care for her dying husband, whom she had never divorced. In detailing the formal, material correlatives to Caland’s lived experience, Tête-à-Tête manages to be truly revelatory—for example, by including five tiny sculptures from 1983 and a terrific collection of sketchbooks—while completely downplaying the idea that Caland is a new discovery.

Huguette Caland, Mustafa, poids et haltères (Mustafa, Weights and Dumbbells), 1970. Ink on paper, 12 1/2 × 9 1/2 inches. Courtesy the Drawing Center.

Caland made her artistic debut in 1970, with portraits of herself, her husband, and a man named Mustafa (her paramour in Lebanon at that time), at Beirut’s legendary cultural center Dar El-Fan. She staged her second solo exhibition in 1973 at Contact, another major Beirut-based institution, run by the critic César Nammour and the Aleppo-born Iraqi artist Waddah Faris. When Faris decamped to Paris and opened a gallery there, following the outbreak of Lebanon’s civil war, Caland joined him and, in 1980, showed her “Bribes de corps” paintings, describing them memorably as her magnificent asses. Since then, Caland’s work has been exhibited consistently, internationally, all the way through her appearances at Prospect 3 in New Orleans, “Made in LA,” Christine Macel’s Venice Biennale, one solo show at Tate St. Ives, and another at the (since shuttered) Institute of Arab and Islamic Art in New York. This summer, her paintings are hanging alongside works by Ruth Asawa, Louise Bourgeois, and Joan Mitchell, among others, in the Centre Pompidou’s self-consciously corrective Elles font l’abstraction.

Huguette Caland, Bribes de corps (Body Bits), 1973. Oil on linen, 60 × 60 inches. Courtesy the Drawing Center.

What’s most notable about Tête-à-Tête is the intellectual armature it creates thanks to the fine, searching scholarship of the catalog, which features Gilman’s argument for enclosure and escape; Hannah Feldman’s emphasis on grids, cityscapes, and urban shorelines in Caland’s work; and an exchange between the artist Marwa Arsanios and her cousin, the writer Mirene Arsanios, who wrestle with Caland’s stature. Also significant in this regard is the inclusion, via daily screenings, of photographer Fouad Elkoury’s majestic new film Letters to Huguette. In a series of missives to Caland, he narrates half a year of revolution in Beirut and declares the foundations of the Lebanese state to have been fraudulent from the start. “You, who loathes privilege and ass-lickers,” he says to Caland, celebrating her life and mourning her death, “would be wholeheartedly with the street.”

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie is a writer and critic who divides her time between Beirut and New York. A contributing editor for Bidoun, she writes regularly for publications such as Artforum, Afterall, and Aperture. Her first book, Etel Adnan (Lund Humphries), on the paintings of the Lebanese-American poet Etel Adnan, was published in 2018.