Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Naya Beat reissues Punjabi Disco, one of the first British South Asian electronic dance albums.

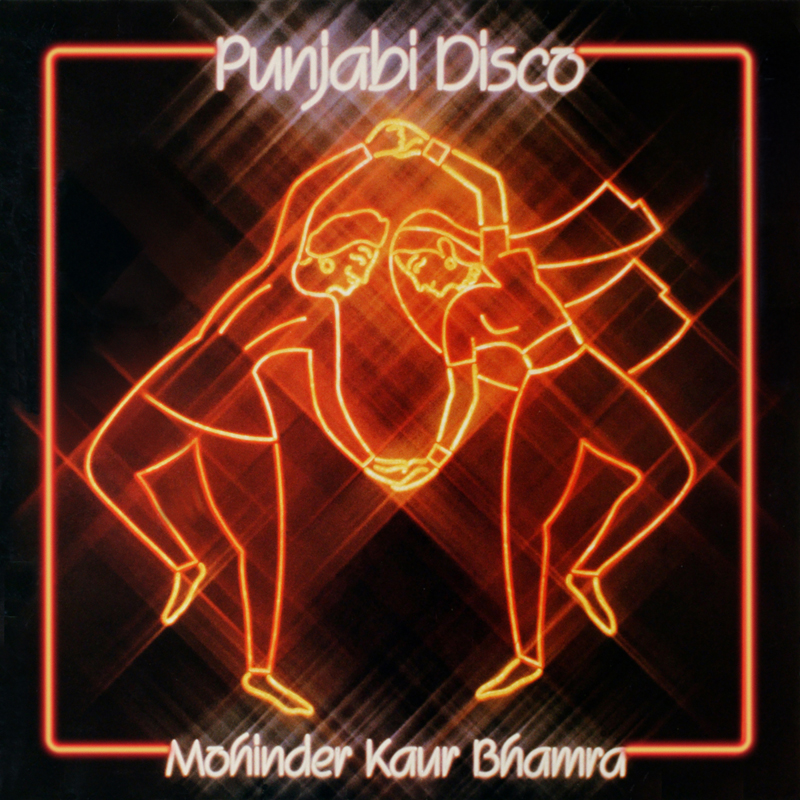

Punjabi Disco, by Mohinder Kaur Bhamra, Naya Beat

• • •

It’s a tale that sounds almost too improbable to believe: a fantastic disco record, created in London in 1982 at a studio belonging to Roxy Music’s bassist, then hidden from view for four decades, is miraculously unearthed from half-forgotten, decaying master tapes. The vocals are not by your standard disco diva; they are by a middle-aged British-Punjabi mother who was known for reciting holy scriptures and singing at gurdwaras (Sikh temples) and Indian weddings. She is backed by her family, a group of largely self-taught musicians and their bass player friend, with an eleven-year-old programming the drum machine. Despite the album’s brilliance, it stays under the radar, partly thanks to the record label not releasing enough copies and possibly even ripping off the idea, handing over the concept to a different artist. But now this formerly rare collector’s item, titled Punjabi Disco, is finally getting its proper due, recently reissued to the public by the label Naya Beat and combined with a range of fresh remixes by contemporary producers.

Mohinder Kaur Bhamra performing at a private event, ca. 1980. Courtesy Kuljit Bhamra.

Punjabi Disco was prescient in several ways. It was one of the very first British South Asian electronic dance albums. It also bridged the gender gap. At the time, Sikh communities were often separated at celebrations, with men and women divided. Mohinder’s upbeat, danceable music brought people together. “Mohinder was a really true feminist,” Raghav Mani, cofounder of Naya Beat, observed to me in an interview. “I mean, that kind of traditional feminist, very steeped in culture, but someone who believed that men and women deserved to be on an equal footing. She would actually insist for the women to be in the room before she even performed. In many ways, this album was really born [from] this desire to kind of get men and women to dance together on an equal level [and] footing at the social functions.”

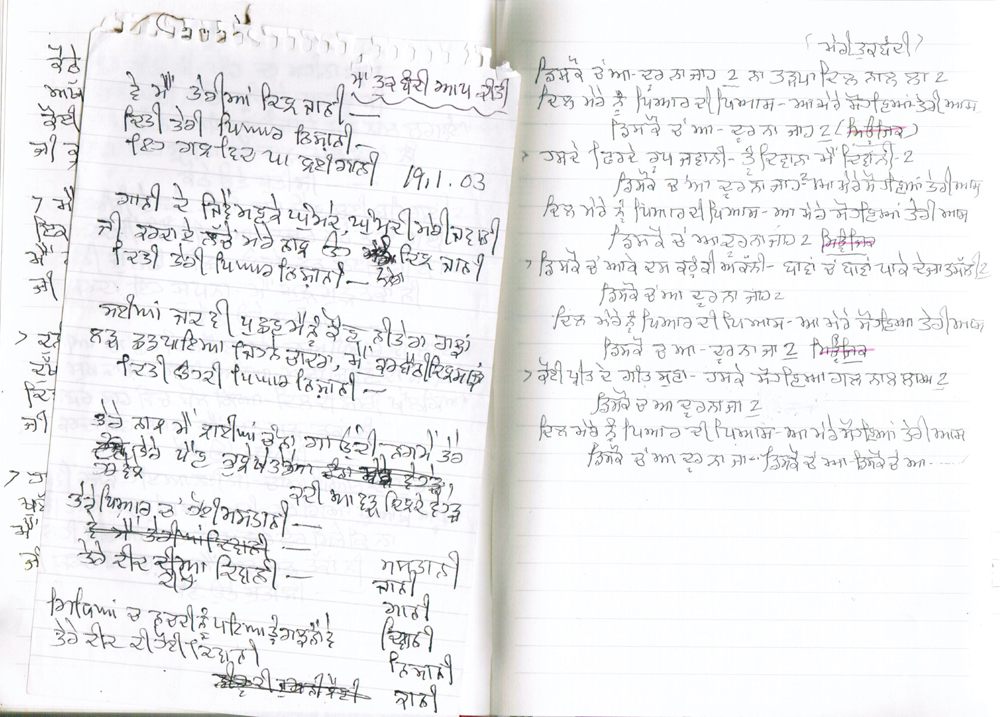

Original “Disco Wich Aa” lyrics written by Mohinder Kaur Bhamra. Courtesy Kuljit Bhamra.

The album is also unique in that the words were mainly penned by a woman. Mohinder’s son Kuljit Bhamra encouraged his mother to compose her own lyrics. “I wanted my mum to write lyrics as well, because she always wanted to,” he told me. “We were always upset with lyrics that were written for her, because they were written by men and they were never accurate to a woman’s feeling. So it was an opportunity for my mother as well to also write songs from a woman’s point of view, rather than from a man’s point of view of what a man thinks a woman is feeling.”

Mohinder Kaur Bhamra performing with her sons Kuljit and Ambi for Indian Independence Day in Bedford, UK, ca. 1980. Courtesy Kuljit Bhamra.

Punjabi Disco further broke ranks with other popular South Asian pop music of the time in that it had absolutely nothing to do with Bollywood. Disco was coursing through Bollywood in the early 1980s, with movies galore featuring light-up dance floors, sparkly bell-bottoms, and over-the-top tunes. But Punjabi Disco’s ecstatic mix of Punjabi vocals with electronic rhythms, produced by then twenty-one-year-old Kuljit—now a legendary composer, musician, and bhangra producer—was more inspired by the movie Saturday Night Fever and the music of the Bee Gees and Boney M. than by anything Bollywood had to offer.

Kuljit Bhamra pictured with the CR-8000 drum machine (top left) in his home music studio in Southall, London, ca. 1982.

Kuljit taught himself to play percussion at the age of six, learning tabla by listening to recordings and following along. He began accompanying his mother at musical performances. For the disco project, he abandoned acoustic instruments in favor of a fully electronic sound. In 1981, he procured a Roland SH-1000, a compact 1970s analog keyboard synthesizer, and the Roland CR-8000 CompuRhythm analog drum machine. Punjabi Disco sounds so unique and whimsical because it is so richly layered with different timbres. The album’s playful beats were festooned with preset sounds from the candy-colored buttons, like “Samba” and “Bossa Nova,” on the drum machine. (Curiously, they never utilized the “Disco” option, deeming it too boring.) In some tracks, it seems like they were using every kind of effect they could get their hands on and cramming it all into one song. The Roland SH-1000 had several presets, too—at the touch of a button, it could simulate a variety of horns and other instruments. In part thanks to the uninhibited use of presets, Punjabi Disco doesn’t sound smooth and ultraprofessional, like much mainstream music of the 1980s. The lack of commercial slickness is one of the things that makes the album so charming.

Ambi Bhamra playing the Roland CR-8000 CompuRhythm drum machine. Photo: Gulab Chaggar.

It features nine tracks that span a wide spectrum of emotions, from energetic party music to soulful ballads, plus a bonus track, “Dohai Ni Dohai,” which was previously unreleased. The rollicking opener, “Disco Wich Aa,” starts things off with a bang. Pulsing percussion presets and catchy synth melodies set the tone. Mohinder’s assertive vocals call everyone to the dance floor. The next song, “Nainan Da Pyar De Gaya,” is a bit more restrained, showcasing Mohinder’s expressive voice.

Mohinder Kaur Bhamra at home, ca. 1979. Photo: Darshan Singh.

From start to finish, the album maintains a relatively fast pace, even in its more melancholy and sedate segments. “Aye Deewane,” for instance, ratchets up the intensity with disco synth stabs and a propulsive bassline. Several new remixes and reworkings add a novel perspective; of particular note is the contribution from Peaking Lights, who modernizes “Disco Wich Aa” with a rubbery acid-house bassline and spacey, hypnotic vocal effects.

Kuljit Bhamra, Mohinder Kaur Bhamra, and Amarpal (Ambi) Bhamra. Photo: Gulab Chaggar.

Mohinder Kaur Bhamra and her group were pioneers who merged traditional Punjabi sounds with electronics well before the tidal wave of British Asian electronic music in the 1990s. This album is another welcome find alongside other visionary South Asian records, like Charanjit Singh’s prophetic 1982 acid-house opus Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat.

Punjabi Disco was bold for both its sonic innovation and its progressive ideals. For Mohinder, now eighty-nine, its renewed popularity—it has already sold out, with more copies on the way—should be a source of great pride. Its rediscovery reminds us that great music often happens in the margins, many years ahead of its time.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World (Bloomsbury, 2009), a book on Brian Eno, and is currently at work on a new book on music.