Hanif Abdurraqib

Hanif Abdurraqib

A life in language: a thoughtfully curated essay collection reveals a pathway through the mind of John Edgar Wideman.

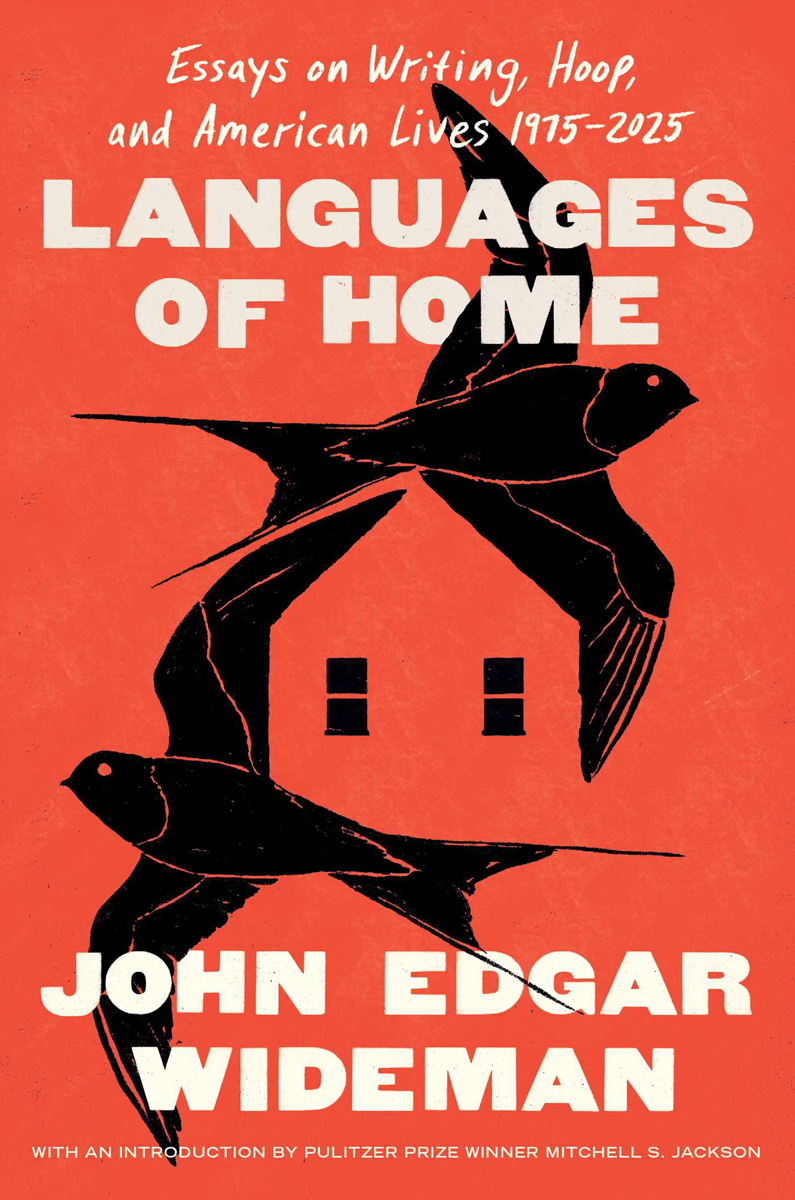

Languages of Home: Essays on Writing, Hoop, and American Lives 1975–2025, by John Edgar Wideman, Scribner, 382 pages, $29

• • •

Of the many “Art of Fiction” interviews that generously exist in the Paris Review archives, the John Edgar Wideman piece is among the ones I return to most often, for how it illuminates the way I’ve always taken him in as a writer, and as a critic: as insightful as he can be curmudgeonly, as firm as he can be direct, but always incredibly rooted in his principles and convictions. He believes that America is fundamentally dishonest about its past (and present), and he believes one way to correct dishonesty is to look closely and with care at the people who are directly in your personal proximity, something he has done throughout his body of work, which makes one of his answers, toward the end of the interview, intriguing to me. When asked the age-old question of who he believes his audience to be, Wideman first says, I am my audience. That isn’t the whole answer—Wideman mentions that he imagines an auditorium of people, Ishmael Reed, his mother, T. S. Eliot, all reading him, but ultimately, the central audience is the self.

I found myself especially interested in this response as I imagined it manifesting throughout Languages of Home, a collection of Wideman essays spanning nearly an entire life in writing, from 1975 to 2025. I was interested in a revisitation of it because the Paris Review interview was from twenty-three years ago, when Wideman was sixty. He’s eighty-four now, and Languages of Home feels like a text distinctly engineered to find and meet an audience—a text that seems to be concerned with both time and legacy, absolutely work that can be done with one’s back turned to the auditorium, but it is also work that is done better with at least a vague understanding of the fact that the auditorium is full.

The other, more urgent question I found myself wrestling with is the question of how to assess whether or not a book like this is a success. Wideman is a writer of titanic skill. He explores predicaments of race, place, sport, and music with a close attention, and he articulates his explorations—as intimate as they may be for him—in a way that is inviting, not alienating. Take, for example, the 1978 piece “Stomping the Blues,” a deep dive into rituals in Black music and speech, which has a lot of balls in the air from the jump: folk and blues and metaphor and old Black scholars and their older texts. But Wideman, right when the population of the essay seems to be at a breaking point, pulls it all back to the church, which had, it turns out, been there the whole time. When he writes “The words of a Church of God in Christ preacher as they stretch and mutate and go on back home and down home where the congregation needs them to be,” he is illuminating his own gift, whether he knows or believes it or not. Stretching out multiple ideas and concepts until there’s a wide enough path for all of them to lead to the same home base.

Language, and dialect, as it relates to Blackness and the Black experience is a central obsession in Wideman’s massive catalog of genre-expansive work, which I hadn’t realized until taking a step back from Languages of Home and appreciating the many different ways into the obsession that Wideman found, spanning decades of his life. In the ’80s, he uses the author and activist Charles Chesnutt as an access point, beginning with the roots of the African American oral tradition before quickly turning toward the shape and musicality of the language, musing on the “dats” and “dems” that appear in the dialect, before turning back to Chesnutt’s prose and the characters within, the language and dialect they are given in the writing of Chesnutt, a man of mixed-race identity who passed as white in the 1800s. And so, you realize, Wideman is speaking less about dialect, and more about power. But language is the bridge that you cross to get to the revelation. Even when contemplating Michael Jordan, in 1990, Wideman takes time to momentarily obsess over the dialect of the taxi driver taking him to a Bulls game, delighting in his “Middle Eastern–flavored Chicagoese.”

This obsession, I think, can be attributed to Wideman’s answer of audience. Throughout the book, it is not just his close attention to language that haunts his entry into larger questions, though that is the most prominent thread. It is also his close attention to people, to place, the close eye he turns to the body and the body’s movement, and how he does it with precision: in a 1996 piece, he speaks of Dennis Rodman “kangarooing” down the court, which sent me to find a video of Bulls-era Rodman, indeed, bouncing in little leaps across the United Center floor.

In this way, yes, the audience is the self, because, it seems, Wideman is plenty sustained by his own interests, and to bring them to life is to prove that they are worthy of the mind and heart’s labor, or to prove that all he focuses his close attention on is deserving of a world of its own. However, I felt comforted spending time with this much of his work at once, over this many years, and coming away with the realization that you can sink deep into a world of your own making and still invite others in. You can be obsessed, but not cold, or distant, or inaccessible, and you can maintain that hunger for decades.

As to the second question, which is the one of success. I believe that a book like this, as a life is into its eighth decade, can be a book that, simply, says look at what this brilliant person has done for so long. And I believe that is enough. Wideman is certainly a talented enough writer to build a monument to in the form of collected works. However, I think the triumph of Languages is that it goes a step further, largely through thoughtful curation, to give us a pathway through the mind of Wideman. His beliefs, his principles, his willingness to explore and not detach himself from his themes and the central engine of his oeuvre. If there is a way to approach this kind of text through a binary of success, I think it might be a book that feels especially useful for a writer to spend time with. To be witness to a life in language, someone who has done it for a long time, and compromised nothing.

Hanif Abdurraqib is from the east side of Columbus, Ohio.