Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

The artist’s endless appetite for all manner of making and creativity is on display in MoMA’s new retrospective.

Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective, installation view. Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. © Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective, curated by Cara Manes and Janet Bishop, with Dominkia Tylcz, Marin Sarvé-Tarr, and William Hernández Luege, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through February 7, 2026

• • •

In the years since Ruth Asawa’s death in 2013, her sculptures have reemerged as the epitome of the mid-century modern aesthetic, with their impossibly graceful, biomorphic, semitransparent wire constructions that most often hang from the ceiling, alone or in groups, casting delicate shadows onto their surroundings. Her renown today—robust enough that Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective is the largest solo show by a woman artist ever held at the Museum of Modern Art—is thanks to a series of important exhibitions mounted over the past ten years, including those at the Pulitzer Foundation, the Menil Foundation, Modern Art Oxford, the Whitney Museum, and David Zwirner’s galleries worldwide, most of which have focused on these pieces. She fashioned them by looping single strands of iron, galvanized steel, copper, or brass wire over and over, creating openwork shells that often contain other elements dangling within, a remarkable feat of three-dimensional thinking. It is easy to imagine her painstaking, repetitive practice as meditative, a way to keep hands busy, to lose oneself in the act of making. The resulting forms are cool in multiple senses of the word—chic, serene, and slightly aloof, not unlike the image of the artist herself as seen in the widely circulated photos by Imogen Cunningham, which often portray Asawa nestled inside or otherwise veiled by her sculptures, just slightly beyond our visual grasp.

Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective, installation view. Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. © Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc. Pictured, back wall: both Untitled (Wall-mounted Paperfold with Horizontal Stripes), ca. 1950s. Ink on paper.

Tellingly, Cunningham’s portraits are not included in the current retrospective. Instead, we see photographs by Elizabeth Jennerjahn and Hazel Larsen Archer, as well as documentary film footage of Asawa at work, all of which give us a new sense of the artist’s presence—playful, always moving, powerful. Among this show’s achievements is its acknowledgment that Asawa’s oeuvre extended far beyond the elegance for which she is best known, and that, far from being aloof, she was deeply enmeshed—energetically and joyfully—with family, her community of artists and friends, and San Francisco, the city where she spent most of her adult life.

Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective, installation view. Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. © Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc. Pictured, left wall, far left: Peace March Section, San Francisco Fountain, 1981. Patinated bronze. Left wall, center: Untitled (Preliminary Sculpture Drawing for Hyatt Fountain on Union Square “San Francisco Fountain”), 1971. Ink on paper.

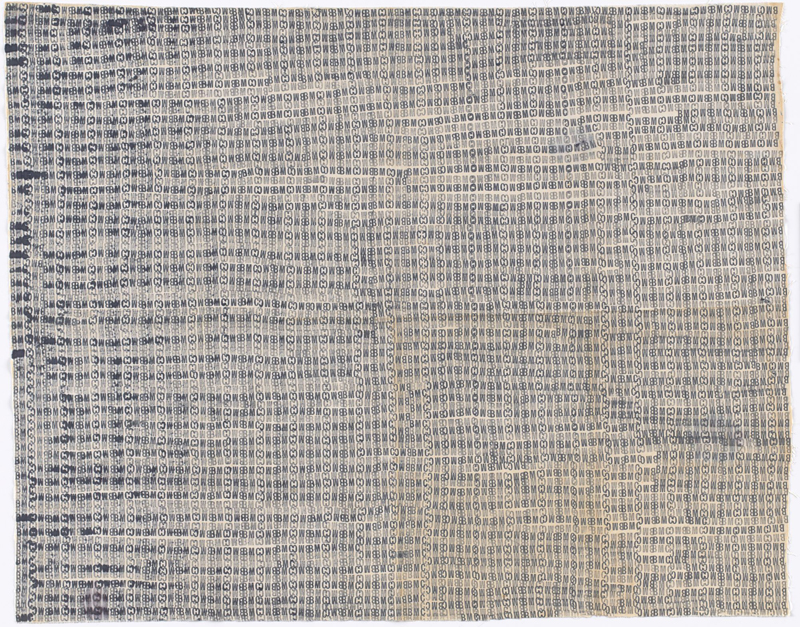

In fact, the more than three hundred objects on view demonstrate that Asawa—and I mean this in the best possible way—was kind of messy. There are even moments when she verges on cringe, with her unapologetically sincere belief in the power of amateur, vernacular, and popular art and craft—she makes all those high modernists of the ’50s and ’60s seem terribly elitist in comparison. There was nothing off-limits for her when it came to medium or technique; she seemed heedless of distinctions between representation and abstraction, high and low, or anything else that would limit her creativity. Over the course of her seventy-odd-year career, in addition to her wire confections (which are abundantly present in the exhibition), she also created drawings from a rubber stamp used in a laundry room; commercial textiles and origami-like, three-dimensional wall coverings; cast bronzes of baby feet and frogs; tender portraits of her children; a mermaid sculpture for Ghirardelli Square; life masks of her family and friends, which she hung on the façade of her house; a proposed fountain intricately decorated with evocations of San Francisco (including a vignette of a group holding a protest sign saying “Jewish Diabetics for Peace”); a variety of projects realized with the help of public school students; and more.

Ruth Asawa, Untitled (BMC.145, BMC Laundry Stamp), ca. 1948–49. Stamped ink on fabric sheeting, 36 3/4 × 45 1/2 inches. Courtesy David Zwirner. © Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

Asawa lived through the trauma of Japanese incarceration during World War II, first in California in 1942 and then in Arkansas. In 1946, after being released from an internment camp so she could train to be a teacher, only to be denied a certification because of her race, she went to Black Mountain College to study with Josef and Anni Albers. Josef, in particular, encouraged his students to push their material and formal ideas as far as they possibly could—for Asawa, that turned out to be an attention to repetitive handwork, openness and transparency, and the charged possibilities of negative space. She traveled to Mexico in 1947 to teach art, along the way learning basket-weaving from Indigenous women—an experience that inspired her later wire sculptures. She injured her hands repeatedly while making them, but, as she wrote to her future husband Albert Lanier in 1948, the trials in the studio were no match for the trials of being in the world. “We have all suffered intolerance innocently. I no longer want to nurse such wounds, I now want to wrap fingers cut by aluminum shavings, and hands scratched by wires; only these things produce tolerable pains.”

Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective, installation view. Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. © Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

Early on in the show, we see projects from Asawa’s Black Mountain College days, often created in response to assignments from the Alberses and other teachers, commercial endeavors, and experimental forays in woven wire. A later, spectacular gallery, brightly lit with stark white walls, includes more than a dozen hanging wire sculptures, all of which were presented between 1954 and 1958 in a series of solo shows at Peridot Gallery in New York. They evoke the alien, the undersea, and even the martial—armored helmets, for example. (Her repeated e-shaped loops bring to mind chain mail as much as an open-weave gauze.) Other rooms home in on her technical explorations (bundling and wrapping wire, crocheting small-scale objects that glow like jewels), her prints and drawings, and her important efforts to expand arts education in San Francisco schools.

Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective, installation view. Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. © Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

But it is in a large gallery taking inspiration from Asawa and Lanier’s house that one realizes the inseparability of Asawa’s art and her life, and the way that inseparability led to an endless appetite for all manner of making. Here we find her incorporating stained glass, with the help of her neighbor, the artist Bruce Sherman, into wire works (Untitled [S. 163, Hanging Tied-Wire, Double-Sided, Open-Center, Six-Branched Spiral Form with Stained Glass], ca. 1976). We see bronzes cast from her wire sculptures, set on bases or left freestanding (Untitled [S. 004, Freestanding Stalagmite Form], 1997), looking like coral or barnacle-encrusted jetsam. Brightly hued depictions of eggplants (ca. 1958) and watermelons (1960s) eschew her graphic drawing style and instead use techniques including impressing painted paper onto the picture surface, resulting in unexpected patterns and textures. She fashioned necklaces out of clay beads, and created decorative ceramic tiles in collaboration with her husband. She devised a portrait bust of Imogen Cunningham (ca. 1953) out of looped iron wire, with an upside-down metal baking pan as pedestal. A devastatingly moving ink-on-paper work (ca. 1962–63) consists of blocks of crosshatched lines representing the thick weave of an undulating blanket, out of which emerges the tender body of her newborn son, Paul. The meandering curves on the redwood doors she carved for her house in 1961 echo a drawing she made at Black Mountain College in the late 1940s: Untitled (BMC.58, Meander—Curved Lines).

Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective, installation view. Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. © Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc. Pictured, center, on mid-ground wall: Untitled (Life Masks), 1960s–2000s. Bisque-fired clay, some glazed. Center right, on mid-ground wall: Doors (Carved Redwood Doors for Ruth Asawa’s Home), 1961.

Among these varied objects, the looped wire sculptures that hang from the ceiling take on a different valence—clearly readable as caught up in the hubbub of life, rather than removed from it. “We always saw her making art, it was part of her everyday existence,” Aiko Cuneo, one of her six children, has said. “I never thought of her making art as a separate activity. To us, she wasn’t working. We didn’t have to be quiet so she could concentrate. Her artmaking space was always in our house.” There were even points when she enlisted her kids to help. What a joy to see Asawa’s creations displayed as the product of the sweet chaos of family and community, rather than cosseted away in perfectly decorated interiors and museum spaces. It feels truer to who she was, and what she wanted her art to inspire.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer and critic based in New York. She contributes to the New York Times, 4Columns, and Hyperallergic. Her new book, Imperfect Solidarities, was published by Floating Opera Press in 2024.