Jo Livingstone

Jo Livingstone

The medieval heart (and loins) knows no bounds in a new exhibition

at the Cloisters.

Spectrum of Desire: Love, Sex, and Gender in the Middle Ages, installation view. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Bruce Schwarz. Pictured, center foreground: Saint Sebastian, late 15th century.

Spectrum of Desire: Love, Sex, and Gender in the Middle Ages, curated by Melanie Holcomb and Nancy Thebaut, the Met Cloisters, 99 Margaret Corbin Drive, Fort Tryon Park, New York City,

through March 29, 2026

• • •

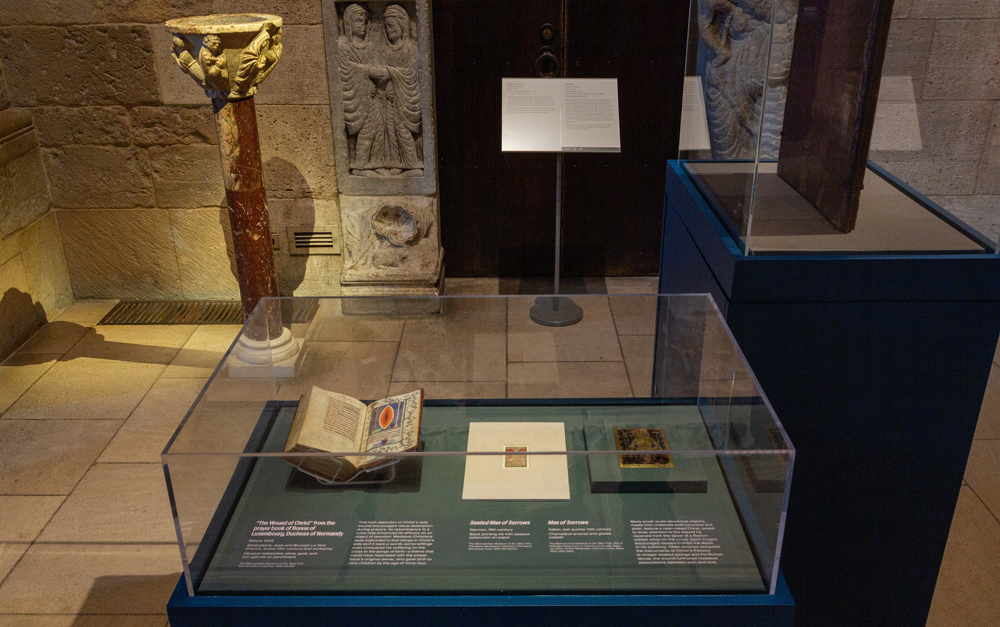

Spectrum of Desire: Love, Sex, and Gender in the Middle Ages is a new show at the Cloisters, that odd assemblage of European monasteries sitting atop a steep hill near Dyckman Street in uptown Manhattan. Clustered in the dimly lit Gallery 2, medieval manuscripts of the bloodiest and most sensual illuminations lie open alongside figurative wood sculptures and metal and textile and ivory objects decorated with erotic scenes—writing tablets, rings, a goblet, a purse, a saddle, multiple locking chests.

Spectrum of Desire: Love, Sex, and Gender in the Middle Ages, installation view. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Bruce Schwarz.

In their introduction to the very fine exhibition catalog, curators Melanie Holcomb (the Cloisters) and Nancy Thebaut (University of Oxford) write that, for the medieval heart, there “is no defense against desiderium,” Latin for desire, “what local vernaculars expressed as dezire, desir, desyr, or begern.” Desire in this culture functions as a libidinal force provoked and fed by imagery, which recirculated through religious, bodily, and philosophical concepts. It’s not an easy process to break down into elements or mechanisms, but you feel it when you look at the most famous image in the show, an illumination depicting Christ’s side wound as an independent, disembodied shape.

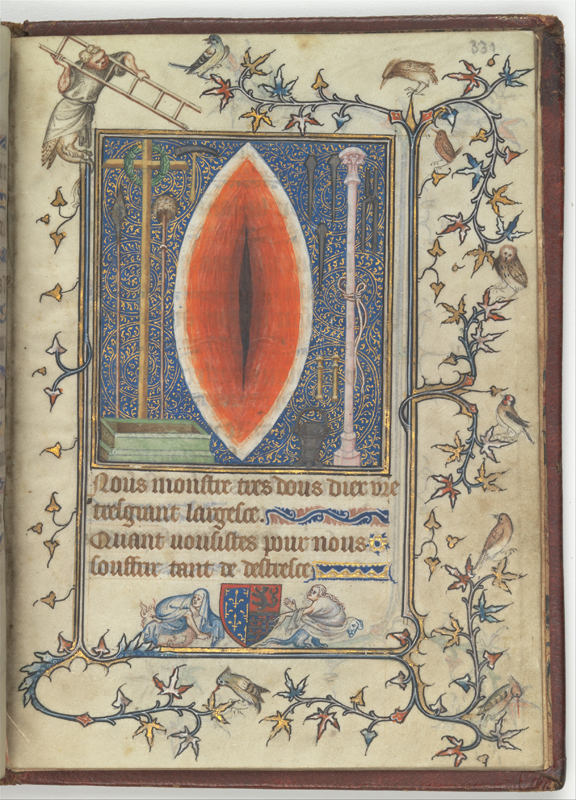

Attributed to Jean le Noir and workshop, The Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, Duchess of Normandy, before 1349 (detail of the wound of Christ).

Jean le Noir and his daughter Burgot, the “enlumineresse,” probably designed the manuscript for a young Bohemian princess. Between the instruments of Christ’s torture and killing, black slashes through a long, red pointed oval—a shape known as vesica piscis, “fish bladder.” “The painting is strange, perhaps even shocking for many modern viewers,” Holcomb and Thebaut write, “not least because its orientation, colors, and shape strongly suggest a vulva.” It looks as much like the Eye of Sauron as it does a naturalistic muscle tear; the curators propose the peeking void tempts the eye to penetrate it and discover the blended meanings of blood, sex, suffering, and piety.

Notes in vitrines and on large pieces of fabric hanging from frames—it’s tricky to attach wall text to stone—explain that, for many medieval thinkers, Christ was a mother to humanity. One literary example might be the English Julian of Norwich, who wrote that Jesus breastfeeds us with the blood of his side wound; his agony was the labor pain of salvation. Feminine symbols bore strong, theology-grade meanings for medieval artists, mixed into a largely anti-feminist culture. However, as Carolyn Dinshaw observed in her 2007 essay “Medieval Feminist Criticism,” people engaged in feminist cultural acts frequently. When the English mystic Richard Rolle began hanging out exclusively with women, for example, he switched the language of his writings from Latin to the vernacular, so his girls could understand him. Geoffrey Chaucer, a man, wrote into existence a woman (from the Wife of Bath’s Prologue) who rips up her husband’s misogynist book and then hits him in the face.

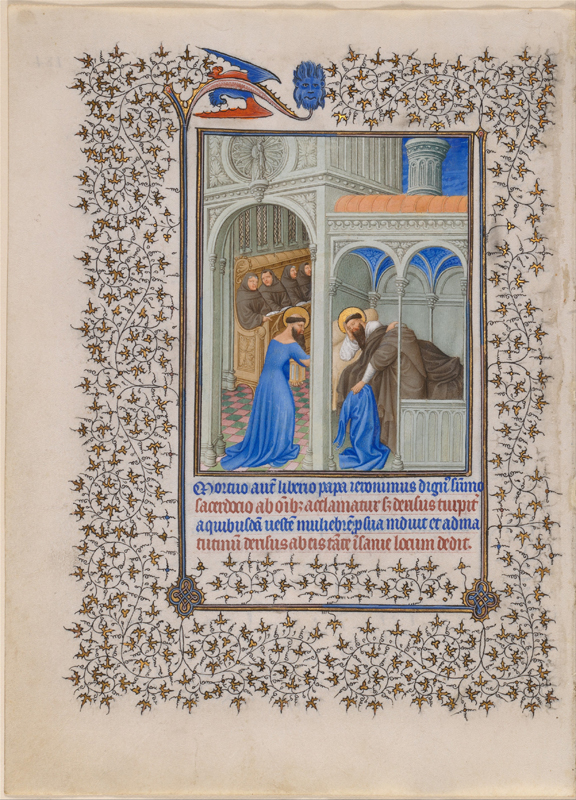

The Limbourg Brothers, Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry, 1405–1408/1409 (detail of Saint Jerome in a woman’s dress). Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Opposing concepts often occupy the same medieval art object; gargoyles are as much a part of cathedrals as are crucifixes. The contradictory desires of our souls, thinking minds, and bodies fascinated great medieval romance poets like Chaucer, Boccaccio, and Marie de France, and all were interested in the erotics of power reversal and humiliation. One of the first items to greet the visitor is a belt adorned with red thread and silver medallions, suspended in the air around invisible loins. Surfaces depict popular medieval stories about sex—Pyramus and Thisbe, Narcissus, Saint Jerome in his dress. One familiar example from French lais of the thirteenth century and the English works of John Gower tells of Aristotle and Phyllis. The famous philosopher was young Alexander the Great’s tutor, the tale goes. Don’t fraternize with your father’s mistress, Aristotle advised Alexander. But Phyllis, the mistress, had already snared Aristotle with her charms. She responded to his advances but made him agree to let her dominate him. She instructed Alexander to hide and learn a different lesson: he saw Phyllis ride the great Aristotle on all fours like a horse.

Aquamanile (water pitcher) in the form of Aristotle and Phyllis, late 14th or early 15th century. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

English poetic versions of this episode pun on the body’s “Silogime” (syllogism) confounding the mind’s “logique” (logic). Any interpretation you can think of for this story works. The pair appear here sculpted in a metal alloy, over twelve inches high. Aristotle is bent gently at the waist, his mortification teaching the story’s moral, the same way the torso curves with emotion in a French limestone Madonna statuette; Saint Sebastian flexes his knee; Christ consoles John the Evangelist, whose head rests in carved wood on his savior’s shoulder.

Spectrum of Desire: Love, Sex, and Gender in the Middle Ages, installation view. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Bruce Schwarz. Pictured: Christ and Saint John the Evangelist, 1300–20.

The Cloisters was begun by the private collector George Grey Barnard, who spent a lot of the first decade of the twentieth century bicycling through the French countryside, looking for medieval antiques. “On occasion he would hire rabbit catchers to scan their territories,” J. L. Schrader wrote in the Metropolitan’s 1979 Bulletin magazine, whose “pay was a franc for a statue with pointed shoes and a half franc for one with blunt-toed shoes, the latter being of the sixteenth century and therefore less valuable.”

Barnard accumulated entire chunks of churches alongside astonishing objects like the burial topper of Jean d’Alluye, which he came across, face down, in use as a bridge across a small stream. Such stories sound far-fetched, but also hanging in Gallery 2 is a classic of his definitely true finds: a truncated figure of Christ carved from poplar in the French Romanesque twelfth century, first encountered cut off at the elbows, knees, and neck and being employed by a farmer as a scarecrow. Once liberated from later layers of gesso and gilding, a carved body in a loincloth emerged that leans at the hips, limbs turned inward, torso impossibly tender.

Spectrum of Desire: Love, Sex, and Gender in the Middle Ages, installation view. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Bruce Schwarz. Pictured: The Visitation, ca. 1310–20.

Young people will learn at some stage that their sexuality has been patterned by certain other forces in life that did not previously seem, on the face of it, very related, like money. Under the global net of structured value—the marketplace of everything—forces of libido govern the motion of money and power, it turns out. Gender, desire, pricelessness: their meanings come from sexual capitalism. You could say that reading Marx (or, more importantly, writers capable of explaining Marx) and critiquing the meta-narratives of history is therefore a stage in sexual development, for the politicized person fucking today.

If the Middle Ages existed before capitalism, which is the axis of our sexuality, then what can contemplating the hot red pussy of a pre-credit-card God do for us? In the simplest and most radical sense it proves that there is desire—there is you—beyond and behind and before and after money as we know it.

Spectrum of Desire: Love, Sex, and Gender in the Middle Ages, installation view. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Bruce Schwarz.

Regardless of our moment in time, sexuality is for all of us a function of the mind, in which memories of money and God and politics and touch loop around one another, lightly and inexorably, like the red threads tangled in the room-size sculptures of the contemporary artist Chiharu Shiota. There is no defense against desire, and desire continually disrupts the control we feel that we have over ourselves, including the feeling that we understand economics and its effect on the fizzing in our guts. Ribs that tilt over pelvises, hands comforting each other in sculpted wood, elbows held just so, the slash in the crimson—they release us.

Jo Livingstone is a critic based in New York.