Albert Mobilio

Albert Mobilio

Playful antics and gentle subversions in two comic books by Joe Brainard in collaboration with fellow members of the New York School.

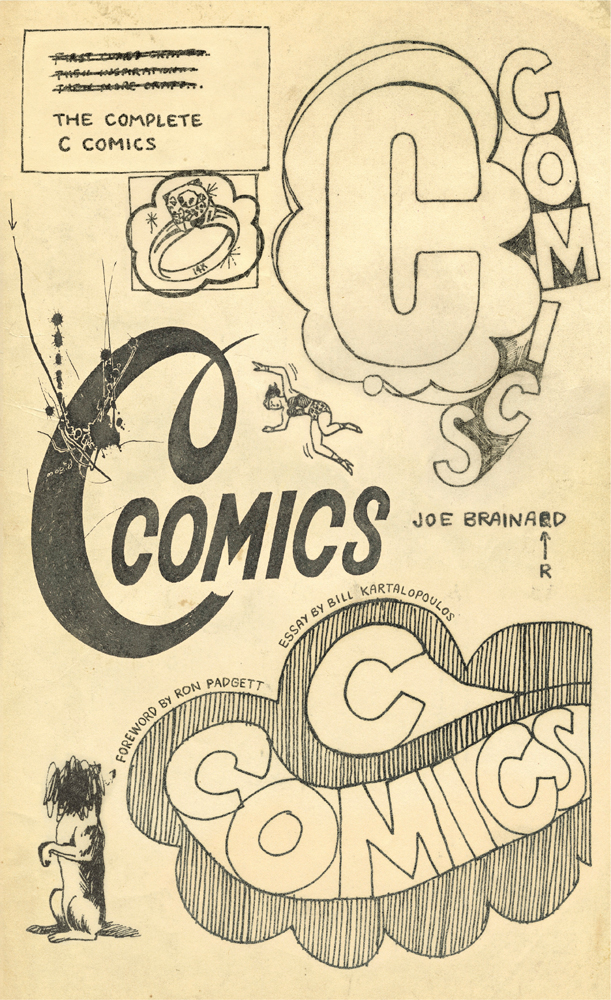

The Complete C Comics, by Joe Brainard, foreword by Ron Padgett, essay by Bill Kartalopoulos, New York Review Books, 200 pages, $45

• • •

Not long out of high school in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1960 Joe Brainard arrived on New York’s Lower East Side, where he began an ambitious project of making art across many forms—collage, drawing, and painting—and writing poems. Joining him in this vibrant downtown culture were fellow Oklahomans Ron Padgett, Dick Gallup, and Ted Berrigan, along with sundry other poets, a list including Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, and James Schuyler. This loose confederation would come to be dubbed the New York School, a term its members would disavow, but which nonetheless serves as a convenient moniker to characterize work that prized urbane wit, pop culture, and a penchant for disjuncture.

Brainard is most famous for the book-length epic I Remember, published over several years, beginning in 1970, which eventually migrated from the rarefied locale where it was composed to creative writing classes all across the country. The 130-page poem consists of simple declarative statements, each beginning “I remember.” While memories, which span childhood (“I remember turning around and around real fast until you can’t stand up”) to Surrealist reverie (“I remember a dream of meeting a man made out of a very soft yellow cheese and when I went to shake his hand I just pulled his whole arm off”), aren’t arranged in chronological order, Brainard’s voice—wry, casual, and seductively personal—unifies the whole.

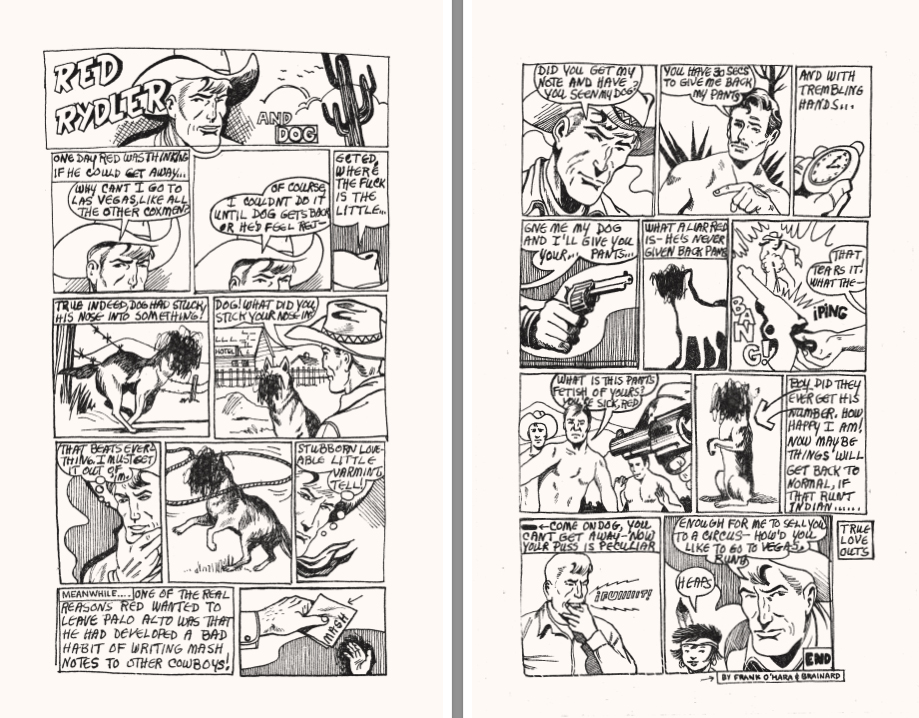

From The Complete C Comics, by Joe Brainard. “Red Rydler and Dog” with text by Frank O’Hara.

That persona, sometimes campy, often profound, can be seen taking shape in The Complete C Comics, a volume featuring an informative essay by comics critic Bill Kartalopoulos and a foreword by Padgett, which presents the only two issues of the comics Brainard produced between 1964 and 1966. The book’s oversize format accommodates the black-and-white legal-size pages from the first issue; the second was the more standard 8 ½” by 11”. Any diminishment in trim size would have been unfortunate: the genre-appropriate boldness of the drawings and energetic design require the full original space.

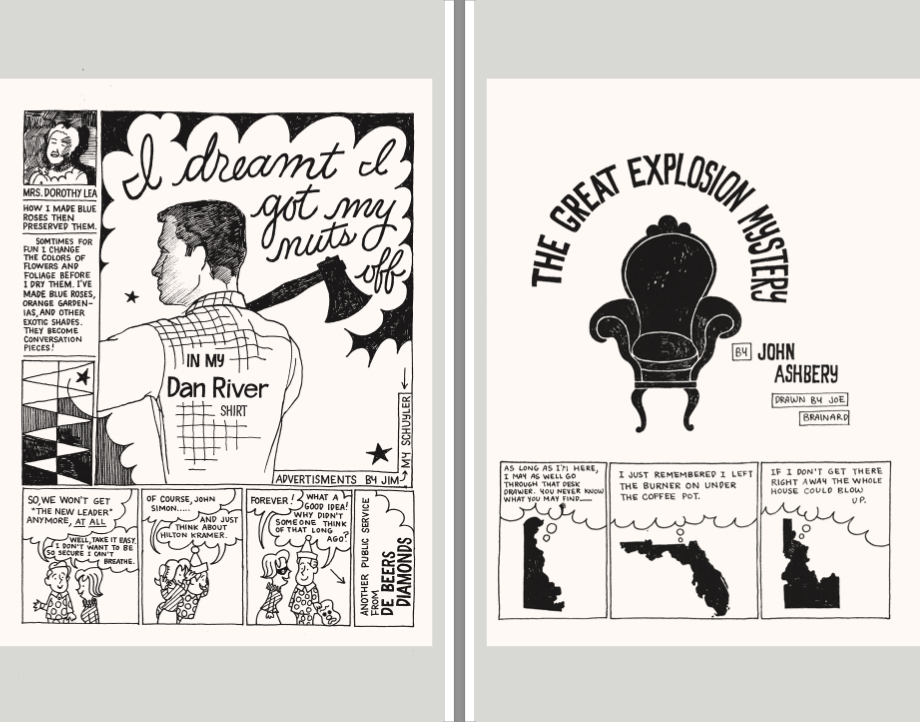

From The Complete C Comics, by Joe Brainard. Left: advertisement by James Schuyler. Right: “The Great Explosion Mystery” with text by John Ashbery.

Brainard (who died of AIDS-induced pneumonia in 1994) and his Tulsa pals were involved in a series of publications; while still in high school, he served as the art editor of a literary journal, the White Dove Review, and drew comic-inspired art for C: A Journal of Poetry, the predecessor to C Comics. Following a DIY impulse, these artists and writers were, as Padgett recalls, “happily free of theoretical ambitions, such as toward being avant-garde or radical or even funny.” An improvisational spirit animated C Comics’ collaborative endeavors. Brainard generated comic book–style pages and sent them to the poets mentioned above in addition to other New York School folks, like Barbara Guest, Bill Berkson, Kenward Elmslie, and Kenneth Koch; they, in turn, provided text for word balloons and captions. (He handed them out “like a teacher’s assignment,” notes Kartalopoulos.)

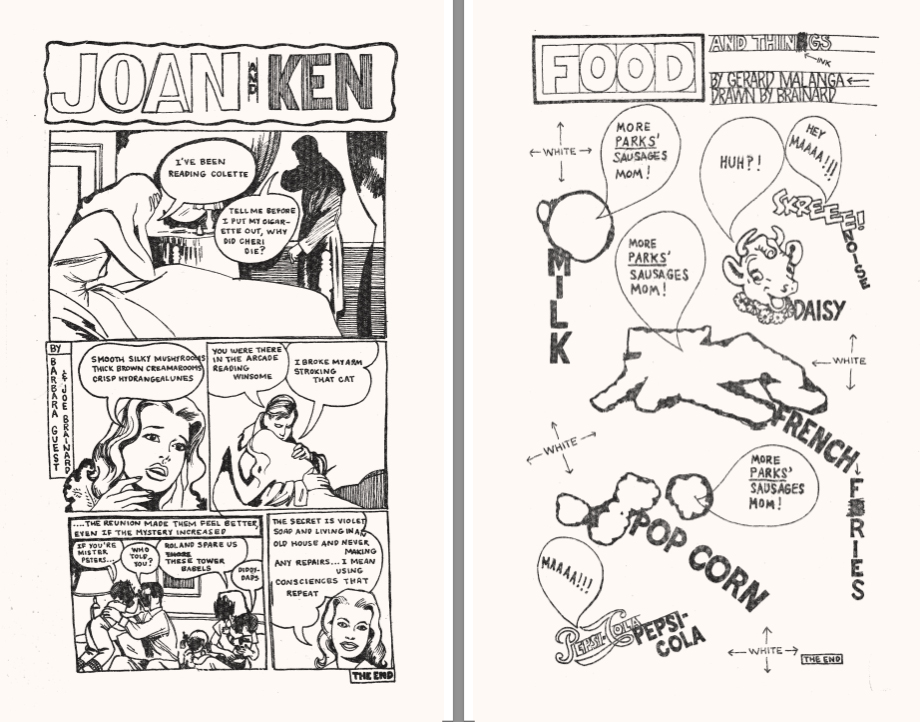

From The Complete C Comics, by Joe Brainard. Left: “Joan and Ken” with text by Barbara Guest. Right: “Food and Things” with text by Gerard Malanga.

The source material for Brainard’s parodic art was familiar to writers who had grown up reading Wonder Woman, Archie, Nancy, back-page advertisements for bodybuilding courses, Hollywood glamour magazines, and Tijuana bibles. Others at the time, such as Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol, drew on a similar visual vocabulary, looting pop culture for subjects that challenged the art world’s sense of suitability. But they tended to create static images like Lichtenstein’s Look Mickey (1961), a subtly altered image of Mickey and Donald from a children’s book. Brainard, instead, appropriated the comic’s narrative display, drawing sequential frames, enabling storytelling. Of course, these were tales told slant by poets.

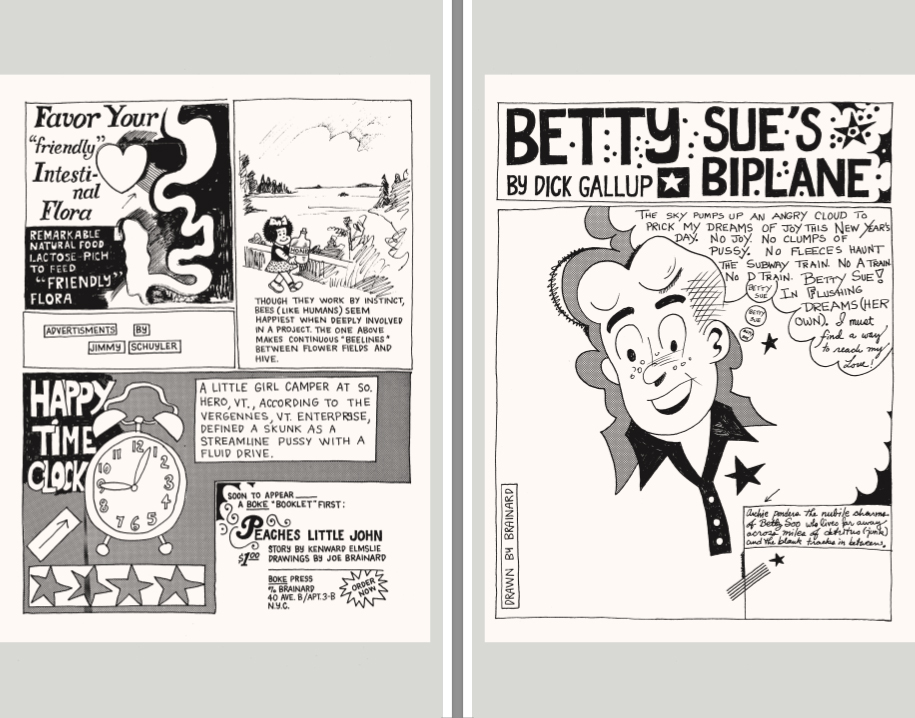

From The Complete C Comics, by Joe Brainard. Left: advertisements by James Schuyler. Right: “Betty Sue’s Biplane” with text by Dick Gallup.

A familiar wide-eyed Archie dominates the initial full-page panel of Gallup’s “Betty Sue’s Biplane,” but there’s nothing familiar about his thoughts: “The sky pumps up an angry cloud to prick my dreams of joy this New Year’s Day. No joy. No clumps of Pussy. No fleece’s haunt the subway train. No A train. No D train. Betty Sue! In Flushing dreams (Her Own). I must find a way to reach my Love.” The caption below this unhinged stream of consciousness hardly clarifies: “Archie ponders the nubile charms of Betty Soo who lives far away across miles of detritus (junk) and the black tracks in between.” Those miles of detritus are perhaps why she needs a biplane, although it’s never mentioned after the title.

From The Complete C Comics, by Joe Brainard. “Betty Sue’s Biplane” with text by Dick Gallup.

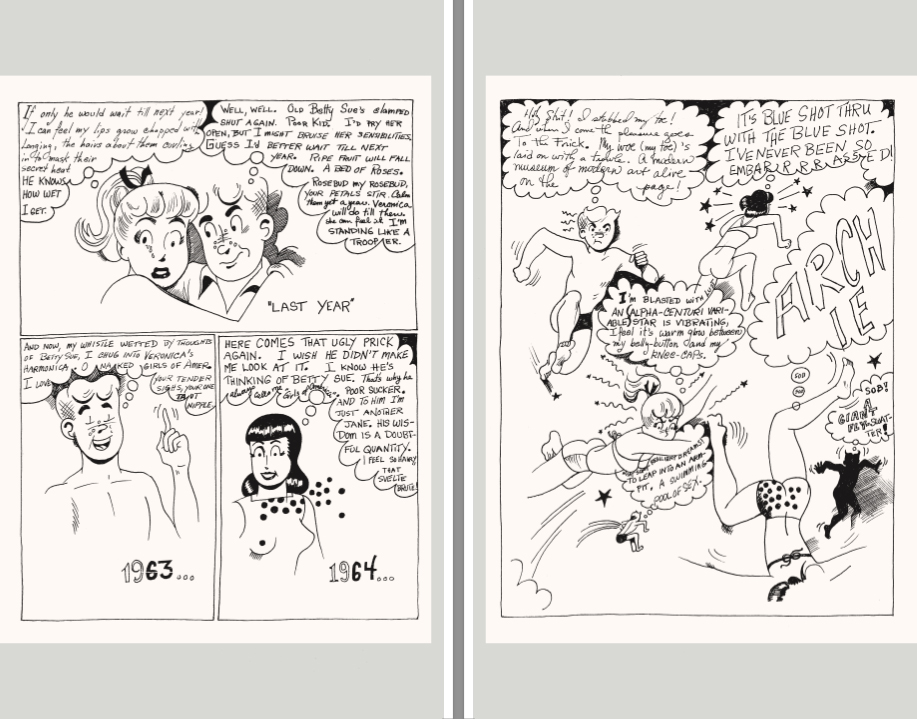

At play is a sensibility—antic, disruptive—sounding notes both juvenile and erudite. In another panel, the breast of a standard-issue Veronica is marked with a polka dot–like nipple as other dots float off her dress to hover in the air. In the preceding panel, Archie strikes a Whitmanesque tone, declaring, “I chug into Veronica’s harmonica. O naked girls of Amer. I love your tender sighs, your one taut nipple.” Archie is then depicted in Superman garb, and in the final panel (jammed with more off-kilter ruminations), the Man of Steel’s cape, boots, pants, and underwear fly skyward, sans Archie.

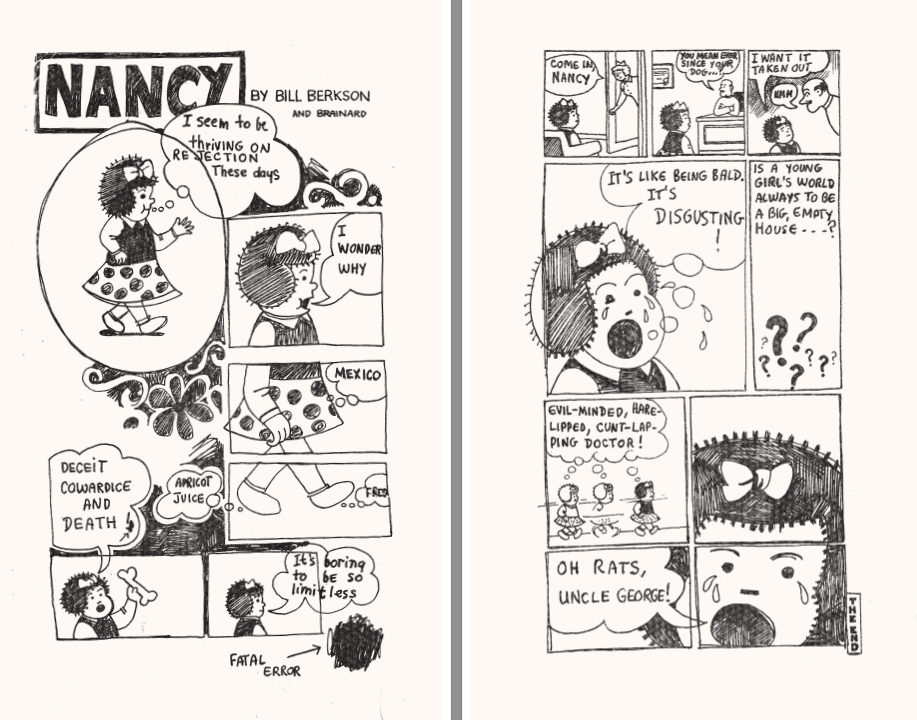

From The Complete C Comics, by Joe Brainard. “Nancy” with text by Bill Berkson.

The subversiveness is gentle; the contributors clearly regarded these comic-book icons with genuine affection. One of Brainard’s favorite figures, Nancy, takes center stage in just two C collaborations, but he would go on to produce dozens more (gathered together by Siglio Press in The Nancy Book). Rendered by the artist in densely hatched, prickly lines, the frizzy-haired eight-year-old appears here with text by Berkson, who directs her to ponder weighty matters: holding aloft a bone, she proclaims “Deceit Cowardice and Death!”; in the next panel, she opines, “It’s boring to be so limitless.” Just above that, Brainard provides a Surrealist touch by segmenting her body into three stacked panels—head, midsection, legs—with thought bubbles for the latter, one of which, “Apricot juice,” is typical of the delight these poets take in non sequiturs and nonsensical jests. At the bottom right-hand corner of this crowded page, Brainard scratched something out, but mischievously called attention to the mistake with an arrow and the announcement “Fatal error.” We are never far, in these drawings, from the immediacy of their creation.

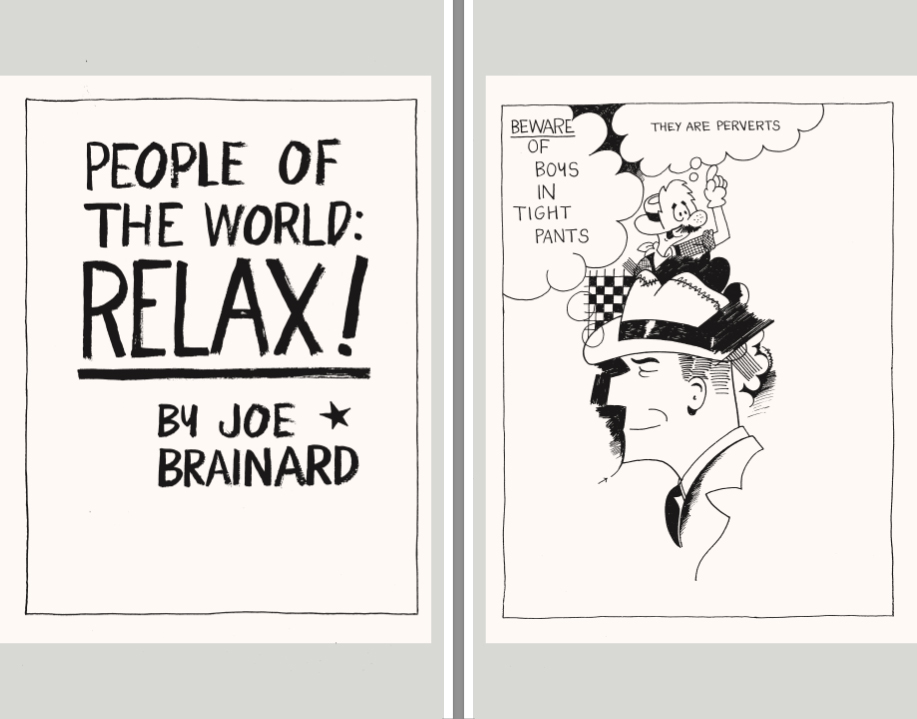

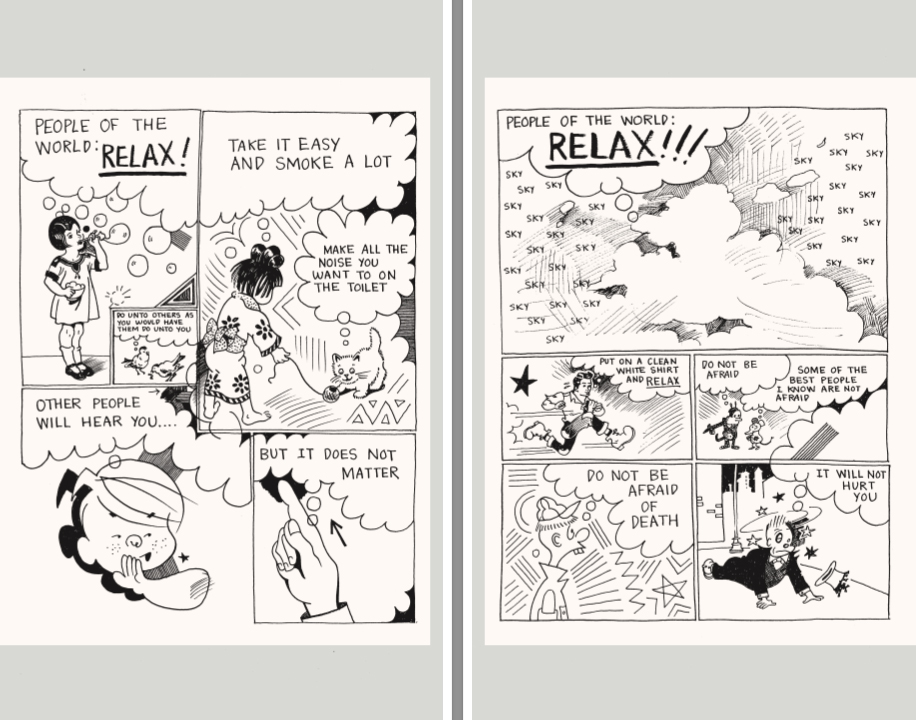

From The Complete C Comics, by Joe Brainard. “People of the World: Relax.”

For “People of the World: Relax,” Brainard supplied his own narrative, which, much in the manner of I Remember, features a quicksilver, congenial humor with lines juxtaposing goofy adolescent jokes (“Make all the noise you want to on the toilet”), philosophical drollery (“Do not be afraid of death / It will not hurt you”), and sly innuendo (“Beware of boys in tight pants”), that last bit showing up in Dick Tracy’s thought balloon. Tracy’s just one member of a virtual pantheon of funny-page stalwarts—Nancy, Tracy, Li’l Abner, Beetle Bailey, Krazy Kat, Little Orphan Annie, Dennis the Menace, and others—faithfully replicated and assembled to expand on Brainard’s invitation for readers to chill out, or more specifically, as Li’l Abner’s balloon reads, “Put on a clean white shirt and relax.”

From The Complete C Comics, by Joe Brainard. “People of the World: Relax.”

This kind of deadpan, absurdist comedy would gain popularity in the next decade, but in 1966 it appealed principally to a coterie of downtown sophisticates; the second and final issue of C Comics sold a total of seventy-five copies at two West Village bookstores. But Brainard’s art now hangs in many museums, and the canon-making Library of America issued his Collected Writings. For a long time, we’ve taken for granted the permeability between high and low culture. The Complete C Comics documents an instance when those barriers began dissolving, a bellwether moment when poets who weren’t supposed to versify on cartoons—and artists who weren’t expected to draw inspiration from Jughead, but Masaccio—did just that.

Albert Mobilio is the author of five books of poetry: Beginning of the Hollow (forthcoming 2026), Same Faces (2020), Touch Wood (2011), Me with Animal Towering (2002), and The Geographics (1995). A book of fiction, Games and Stunts, appeared in 2016 and a selection of criticism, Reading Against Type, was just published.