Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Sounds for quivering organisms: Three Willow Park collects a decade of the electronic composer’s experiments.

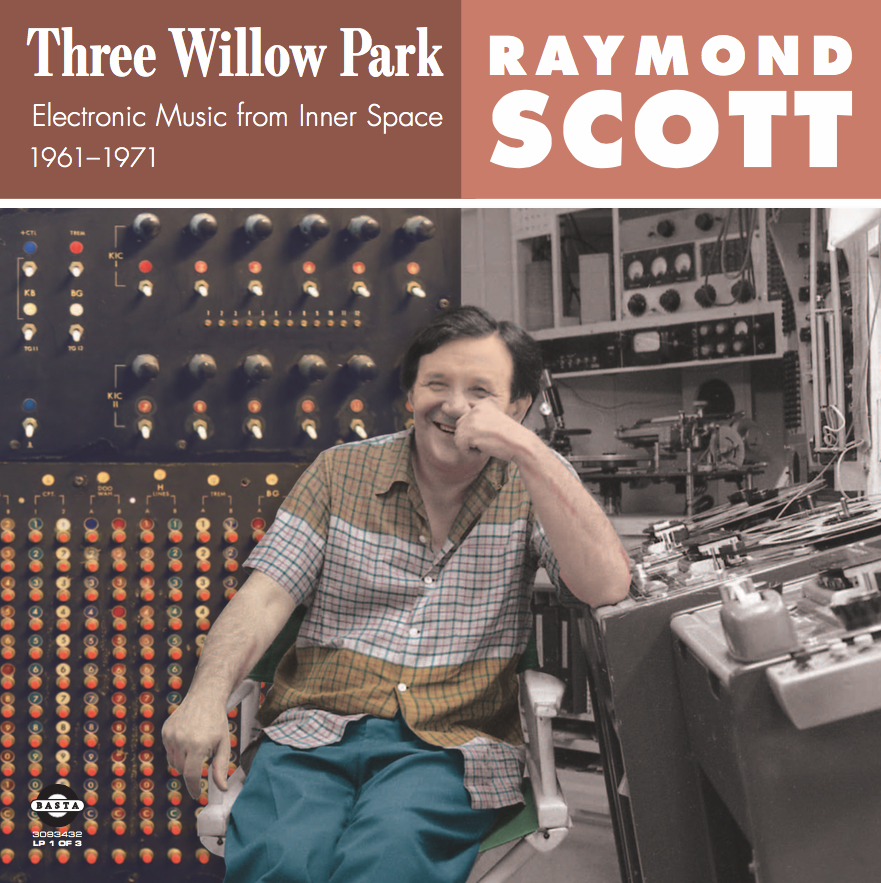

Raymond Scott, Three Willow Park: Electronic Music from Inner Space 1961–1971, Basta Music

• • •

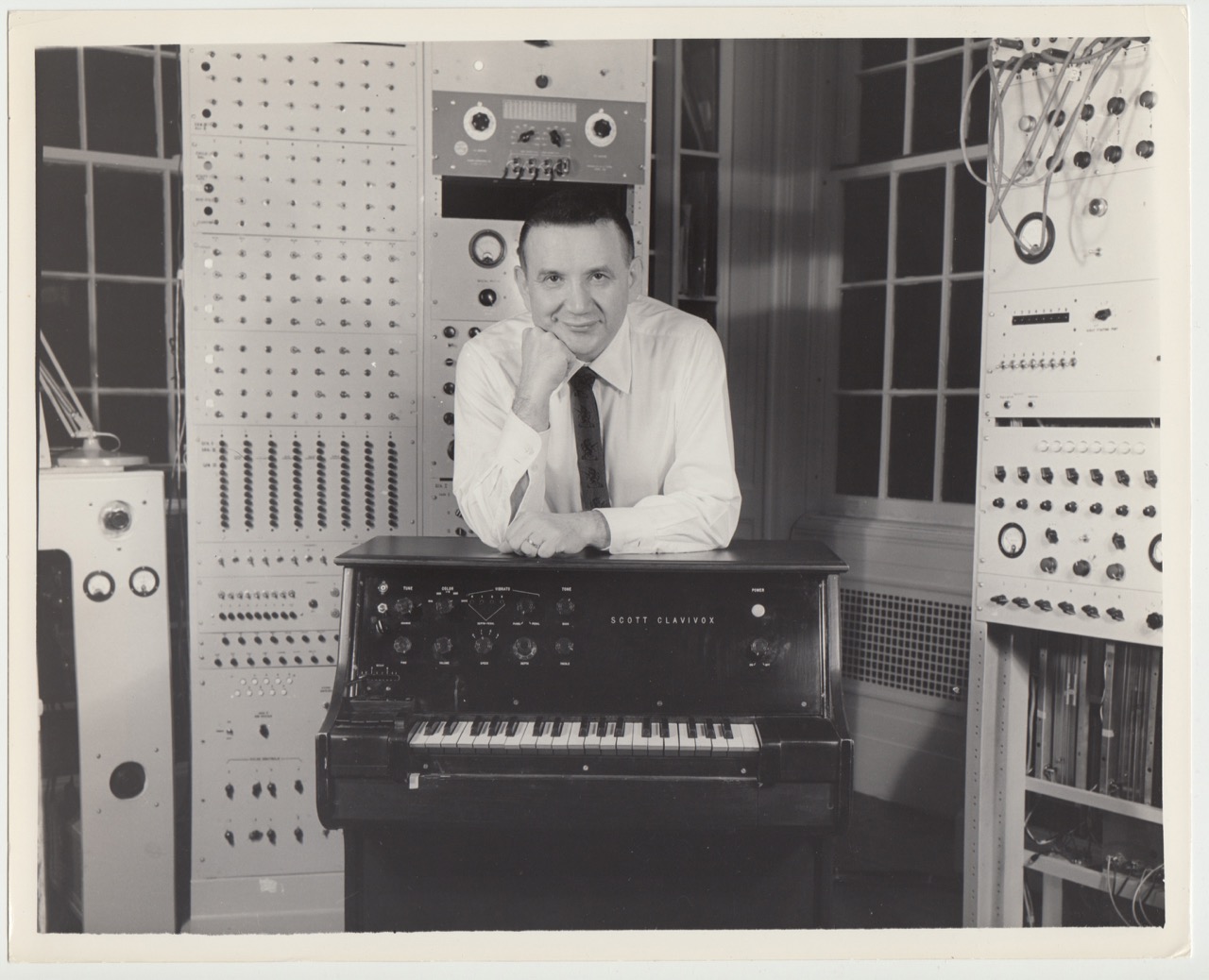

It’s easy to look at the history of electronic music in the 1950s and 1960s through the lens of quaint, bygone distance. Visually, the history of this music is often represented by cool black-and-white photographs—of earnest-looking people (usually men), in sharp single-breasted suits or lab coats, standing in front of walls of impressive analog gear covered in knobs and dials. The black-and-white presentation adds a whiff of gravitas: this was serious-looking equipment, operated by serious-looking people.

Raymond Scott in his Manhasset, New York, recording studio, 1959.

We shouldn’t forget that these experiments actually happened in color—that it was furiously alive music, created by adventurous and spirited people, not by humorless automatons. These composers and inventors often stumbled in their attempts to forge a path ahead for music; their burning curiosity kept them going. Their laboratories, studios, and work spaces were never as clean and perfected as they looked in pictures. (A few months ago in England—while I marveled at a particularly gorgeous vintage photo of a rack of rare synthesizers—their now octogenarian inventor laughed, snapping me out of my reverie. “Do you have any idea how bad it looked from the back?” he said. “And how much bloody soldering was involved?”)

A revelatory new box set of work by the late Raymond Scott, the independent American inventor and composer who began making music in the 1930s, helps to upend the solemnity that we have come to associate with the early days of electronic music. “I hate electronic music, because human beings are quivering organisms,” said Scott, memorably quoted in the expansive liner notes. “My designs, although electronic, always quiver.” Scott died in 1994, and several compilations have been released since his death, including the impressive collection Manhattan Research Inc. This new double-disc set, titled Three Willow Park: Electronic Music from Inner Space 1961–1971, collects dozens more of Scott’s short electronic experiments. The music still quivers, sounding vigorously and strangely alive.

Raymond Scott in his electronic music studio at Three Willow Park Center, 1967. Photo: Jim Henson, © The Jim Henson Archives.

Three Willow Park is named for the industrial complex in Farmingdale, Long Island, where Scott set up his rambling live-in workshop in the 1960s, after he abandoned the more lavish environs of Manhasset. Much of the material on Three Willow Park sounds like Scott never intended it to be released. He was a notorious perfectionist during his life; his expansive oeuvre, while always inventive and odd, also possessed commercial appeal and a professional slickness. Though he was reclusive, he was also a bit of a showman, and his creations had attracted fawning attention in the mainstream press in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. An effusive 1941 profile of Scott in the popular general-interest magazine Liberty proclaimed: “Take William Saroyan. Add a generous helping of Barnum. Mix with equal parts Richard Strauss and Oscar Levant. Stir well with a syncopated beat. The result: Raymond Scott, the Gertrude Stein of Dada Jazz.”

“Stir well with a syncopated beat” is a good description for much of what is on this box set, which was lovingly culled from many hours of unreleased material by Scott aficionados and scholars Irwin Chusid, Gert-Jan Blom, and Jeff Winner. The chugging pulse of “Cindy Flair Look Rhythm” would not be out of place in a techno set today; other tunes, like the chilled-out, woozy “Portofino #4,” would be great sampling fodder for a hip-hop track. On Three Willow Park, we hear how prescient—and instantly enjoyable—so much of Scott’s music was, and how visionary his electronic sounds were, created on hand-built devices like the mammoth Electronium.

Other tracks on Three Willow Park have titles like “Toy Trumpet Demo #1” and “Rhythm Sample #5,” and many of the pieces are shorter than two minutes long. On some of them you hear Scott’s own voice. “This is a sound,” he announces, before unleashing a bubbly bit of music titled “Alka-Seltzer Effects #7.” Other tracks clearly look like they were intended for instructional use—like “Clavivox Demo Intro,” which demonstrates the use of one of Scott’s most famous inventions.

Raymond Scott with his Clavivox and racks of electronic music equipment at his home in North Hills, New York, ca. 1959.

A 349-page book of clippings from Scott’s life titled Raymond Scott: Artifacts from the Archives—including photos, patents, articles, notes, and other ephemera—was recently released for free on raymondscott.net, and is an indispensable companion along with the liner notes for those who wish to dig further into his story. Scott devised a talking alarm clock in 1946; he filed early patents relating to magnetic tape recorders in the early 1950s; he created inventions with names like the “Videola” and the “Karloff,” and drew up schematics for an electronic baby rattle and a spinning pizza-sized device called a “Spin-a-Tune.” He wrote numerous jingles, and created sounds for TV advertisements—for Scott, designing the electronic blips for a Vicks cough drop commercial was just as much of a challenge as writing a “serious” composition.

A common criticism of the current “reissue culture” is that every possible scrap of twentieth-century music seems to be getting exhumed and rereleased in the form of deluxe vinyl gatefolds, extravagant box sets, and remasters, despite the work’s quality or historic importance—or the artist’s original intentions. In this thriving reissue culture, for example, an idiosyncratic artist like the late experimental composer, cellist, and avant-disco maven Arthur Russell gets explored in new ways by new generations of fans—with Russell’s most intimate and uncertain output put on display.

But there is value in showcasing these experiments, as ungainly as they may be. So much of what we hear in recorded music is the finished product—not the studies, demos, and failures along the way. In Three Willow Park, we hear some of Scott’s process—the tentative line drawings before they became fully fledged works. These sketches are not just instructive, but profoundly inspiring. “This is ‘Idea #36,’ ” he announces on one intriguing track, which implies there were thirty-five ideas prior to number thirty-six. One can only imagine what those preceding ideas must have been, and how many ideas came after it.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist, specializing in writing on twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including The Guardian, Wired, The Wire, Bookforum, Slate, The Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.