Rachel Haidu

Rachel Haidu

From empire to the frog symphony: the exhibit’s 2017 edition splits itself across a fractured Europe.

Marta Minujín, The Parthenon of Books, 2017. Steel, books, and plastic sheeting , Friedrichsplatz, Kassel. Photo: Roman März.

Documenta 14, Athens: April 8–July 16, 2017, Kassel: June 10–September 17, 2017

• • •

Documenta 14 might be the most provocatively Eurocentric exhibit that I have ever seen—and I mean that in the best possible way. Unlike Okwui Enwezor’s pivotal Documenta 11 (2002), which replaced the exhibit’s usual highly European perspective by didactically advancing “the global” as a means of thinking through art’s stakes, the six-member curatorial team helmed by Adam Szymczyk could not leave its immediate context alone. What is Europe, the curators seemed to be asking, now that its “unity” has been forced open, laid bare on the autopsy table, and tossed, like so many scraps, to various national elections and referenda? Can Europe, even as a fiction, provide a series of historical lessons in the ways that democracy has evolved, from its Athenian origins through its most recent disastrous ballot results? And given the slow rate at which the supposed “global turn” in contemporary art has affected its institutions, what would it look like if we were to finally begin abandoning the European notions of artistic authorship that still rule our exhibition systems? Might other notions of artistic production—notions that rely not on the paradigms of the genius master and his workshop, the solo practitioner known only by her “best work,” or even the Barthesian “dead” author—enable a fuller critique of Europe’s modes of doing history, and their part in the continent’s cultural hegemony? In Documenta 14, curated by a team that was itself largely European, the edifice of the European author was finally made to quake.

Arriving at a stately quinquennial pace, thereby excepting itself from the rapid overlapping rhythms of the biennials that scatter the globe, Documentas bear a burdensome legacy: the one-hundred-plus artist exhibition began in 1955 as a kind of historical-aesthetic first-aid for German audiences deprived of European avant-garde art by the Third Reich’s culture war. From the mid-1960s to the late 1990s, Documenta defined contemporary art as an almost exclusively American and Western European phenomenon. Enwezor’s edition finally, dramatically, insisted upon a truly international range of artists—a commitment that is present but not as significant in this Documenta. Alongside Enwezor’s anointment of an expanded documentary practice as the prime mover of contemporary art, his Documenta also picked up on the then-rampant excitement over participatory art practices that highlighted the ethical and unethical relationships between artists and the communities their works engaged. If in the broader art world these developments have lately diminished in favor of what can seem like more conventional notions of art making—with live performance overtaking participatory art and painting returning to its kingly place, especially in many gallery scenes—the current Documenta fights back on several fronts.

Painting is not ignored in this edition, though it can at times feel that way. It is instead used, alongside other media, to remind us of the alternative social roles the artist can play: that of interlocutor, of memory-bearer, of political activist-representative, et cetera. Live performance, with a few notable exceptions, is eschewed in favor of performance’s artifacts and scores; moreover, audio works proliferate, their intermittent (and sometimes invisible) presentations shifting away from the register of performance as a matter of live bodies. Thus, we most frequently encounter performance in the form of masks, notations, posters, and archives, enormous or tiny audio-emitting gadgetry. In these and many other ways, Szymczyk and his team seem to demonstrate little interest in what moves markets, including the conventional curatorial agenda of locating and advancing aesthetic trends.

The most dramatic step that the Polish-born Szymczyk took to frame his Documenta was announcing, in the still choppy wake of the European financial crisis, that this Documenta would be held not only in its mild, native German home of Kassel but also in the capital of a country Germany is colonizing, twenty-first century style: Athens, Greece. This bifurcation turns our attention toward a Europe extending its empire not only outward but inward, with Greece, like its neighbors along the southern Mediterranean, providing one kind of internal colony and the nations of the “former East” providing another. The result is a literally doubled exhibit in which the vast majority of artists present work in both cities, giving us points of reference across a contemporary map of neoliberal colonization. In so doing (and particularly given the international array of artists on view), the show evokes several more historical maps of empire, across Africa, the former Soviet Republics, and North America.

Documenta 14’s efforts to underline the contemporary relevance of empire and its histories lie in not only splitting the exhibition but in stripping it of conventional didactics. Without the usual pedantic moralism supplied by lengthy curatorial wall texts, audiences are thrown back on their imaginations. But for those lucky enough to visit both cities, this imaginative element is intensified, made into an effort of memory and projection. We are reminded that no matter where we are at any given moment, there are corresponding works, sites, and artistic tactics in the other city. Thus one is always overlaying Europe’s internal and external empires onto the map of aesthetic experience, and vice versa. This kind of aesthetic de- and re-contextualization provides both a remarkable way to think about art, and one that runs plenty of risks.

One much-maligned example of such risk-taking: the curators took a substantial chunk of the collection of the National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST) in Athens and installed it in Kassel’s Fridericianum, the very heart of that city’s museum complex. This move meant that the temporarily vacated Athenian museum could then be filled with half the Documenta artists being shown in that city. For many, the move’s failure was that the works from the Athenian contemporary museum fell like stones in Kassel. If viewers at Documenta 14 often relied on very sparse wall texts, almost no explanatory texts accompanied the works from the EMST collection (whether in the Fridericianum, online, or in the exhibit’s myriad publications, including a reader, a daybook with short essays on each artist chosen by the team, and several issues of the journal South as a State of Mind). While some schematic reference points are supplied, most audiences are not familiar enough with postwar Greek culture, its military junta (the Regime of the Colonels, 1967–74) and ensuing political turbulence to be able to understand either the context of individual art works on display or the parameters of the EMST’s collection of postwar art. It is for example difficult to guess when the artist Chronis Botsoglou first exhibited his eighteen-panel painted Frieze (1972), a sexy anti-dictatorship work made smack in the middle of the Regime of the Colonels, or who had seen Dimosthenis Kokkinidis’s painting series, And Regarding the Remembrance of Evils . . . (1967–97), begun in the same year as the coup d’état and brightly chastising the American government’s financial support of the Greek junta. Were these works publicly shown when they were made? Were they in conversation with one another? Would it be a mistake to view their politicization of a pop aesthetic as a critique of capitalism as well as the military oligarchy? Were they victims of censorship, heroic exemplars of resistance? And what would it take for non-Greek audiences to move beyond framing the question this way—in terms of the simple binary of resistance and censorship—to see a more complex working relationship between state and artist, state and viewer, state and art?

Edi Hila, Boulevard 1–6, 2015. Installation view (detail). Oil on canvas, Torwache, Kassel. Photo: Michael Nast.

For this viewer, the chance to ask oneself such a rarely posed question is almost worth the frustration at how little information about individual artists we are given. For example, could the category of history painting be expanded to encompass “mere” landscapes, as seen in the gorgeous works, from the 1970s to the present, of the Albanian painter Edi Hila? Could the simple shapes of trees communicate as much about the emptied shell of a totalitarian regime as any painted scene of revolution—such scenes being perhaps inadequate anyway, in the face of ongoing dictatorship?

At Documenta 14, such questions of medium, genre, and formal expression are in turn inflected by the bifurcated Athens-Kassel structure, which allows works to echo and ricochet off each other. While many exhibitions manipulate how works “speak” to one another across a room, the international divide between Documenta’s two sites addresses how complex those relationships can become. In this show, both national histories and imperialist maps ramify how we understand the individual works, and viewers’ imaginations prove crucial to making a meaningful experience of the works at all. Thus, a set of questions about the Greek artists in the EMST collection shown at the Fridericianum in Kassel might not have been answered by anything specific to Greece, or couldn’t be, in this exhibition so poor in wall texts; in its place one could think instead, for example, of the remarkable Congolese painter Tshibumba Kanda Matulu. Tshibumba (whose work is only shown in Athens, just as the EMST collection is only in Kassel) became internationally well-known in the mid-1990s when a monograph by the anthropologist Johannes Fabian, who commissioned and documented the artist’s History of Zaire, was published. The Athens installation of 101 of his small, graphic, often highly sardonic and always brilliantly colored history paintings, interrupted when Tshibumba was “disappeared” in 1981, in the midst of Mobutu’s kleptocratic dictatorship, poses a broad set of questions about how the genre functions in the course of an extended and violent repression. Thus, though the lack of didactics regarding (for example) Botsoglou and Kokkinidis does not allow their works to become better contextualized or understood, the work done by the exhibit’s split framework relentlessly drives home how our reactions to art and its media always engage an international, arbitrary, and overwritten geopolitical map.

Anna Daučíková, On Allomorphing, 2017. Installation view. 3-channel video, Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), Athens. Photo: Mathias Völzke.

At this Documenta one is often aware of how individual artists’ trajectories would intersect with—or become overdetermined by—political realities. One example is provided by the artist Anna Daučíková, whose career reflects the complex trajectory of many who grew up in the Soviet satellite states of the “former East.” Born in 1950 in Bratislava (Slovakia), Daučíková is now a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, but in the 1980s, she was a Moscow-based member of the Soviet Artists Union, a glassmaker, a painter, and a would-be candidate for gender reassignment. In other words, like many of Documenta’s artists, Daučíková has a history, and it is that, alongside the works, that we partially uncover and learn with the help of the exhibition’s daybook or its excerpts online. But the artist’s biography is only one framework for thinking about, for example, her two-channel video Along the Axis of Affinity (2015), which joins the history of state surveillance under Khrushchev to the bizarre evolution of Ukraine’s famous mosaic arts. Under the Cold War leader, that ancient craft, which as recently as the 1930s had translated socialist realist motifs, was reduced to the state-controlled manufacture of anonymously beige ceramic exterior wall tiles. In the course of her video, Daučíková not only asserts that—despite the banal appearances her camera is scanning—“surfaces are where the things happen,” she also narrates the story of a Kiev-based tile-maker, Valery Lamakh (his Books of Schemes, 1969–78, are shown in Kassel), who slipped fragments of his designs and allegedly even political messages into tiled building façades. One is hard-pressed to find such meanings in the familiar decorative geometries and monochrome exteriors that Daučíková’s camera pans over, but then one notices that not only in her other work in Athens, On Allomorphing (2017), but also in her work in Kassel, Thirty-Three Situations (2015), that camera is always panning and scanning. Does such a banal, unvarying mode of looking stand for something with respect to the Soviet visual regime, its specific tradeoffs between secrecy and freedom, surface and interiority? The Steadicam smoothness of her camera highlights how latent meaning from that time could remain unrecoverable today, these many years later. Meanwhile, just as Lamakh’s story suggests that the Soviet visual regime remains thoroughly embedded in the story of industrial manufacture (and the possibilities for resistance it holds out), Daučíková’s efficiently panning camera syncs with the bland surfaces it records. Yet that familiar, aloof, industrially perfected pan also feels oddly, familiarly intimate—and all the more so in her two other videos, which deal overtly with how sexuality relates to a monolithic state. Our preferred recording devices, these days, insinuate latency and secrecy just as effectively as epistles and hidden messages once did.

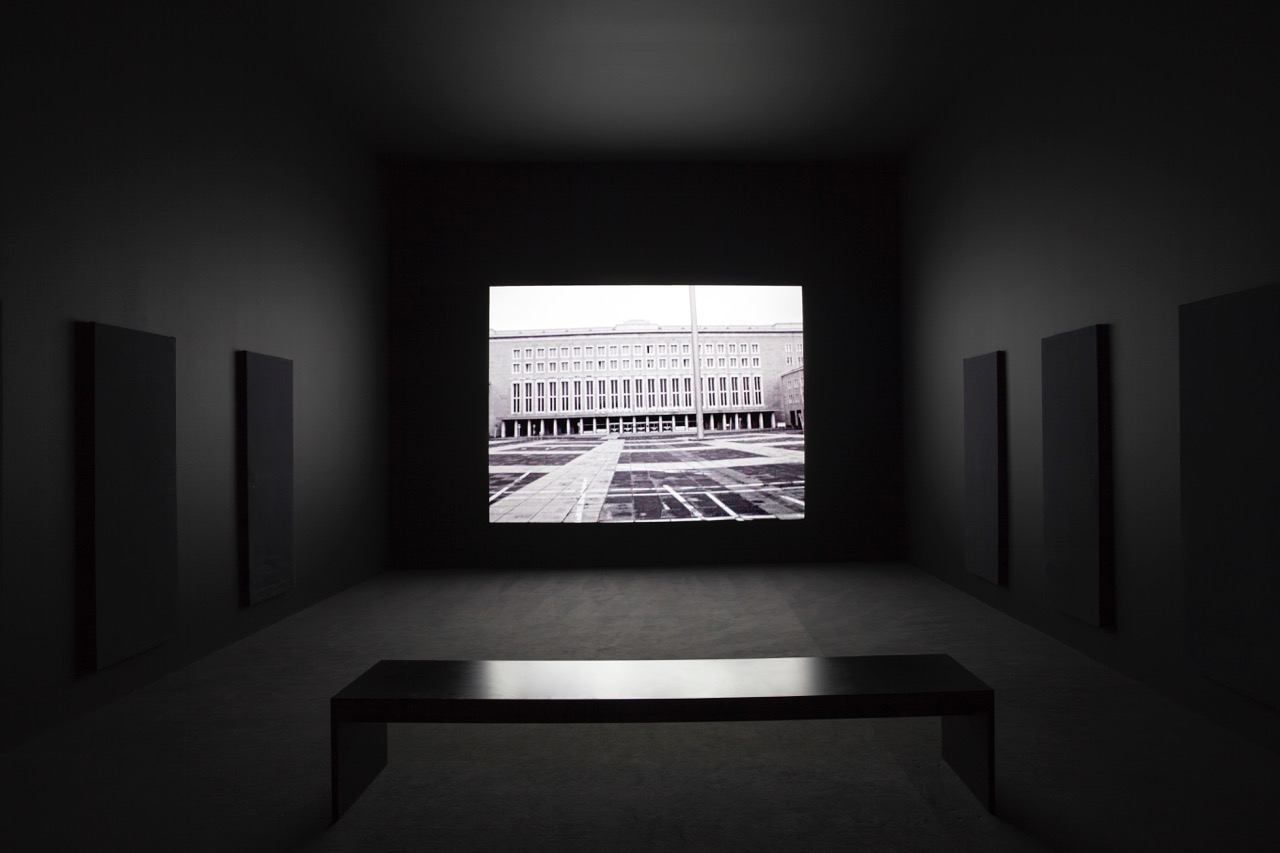

Artur Żmijewski, Glimpse, 2016–17. Installation view. Digital video transferred from 16 mm film, Athens School of Fine Arts (ASFA)—Pireos Street (“Nikos Kessanlis” Exhibition Hall). Photo: Yiannis Hadjiaslanis.

Another, more familiar presence from the Eastern half of the continent, the Polish artist Artur Żmijewski shows his most original new work at the Athens School of Fine Arts (ASFA). Silent, shot on black-and-white 16 mm film, Glimpse (2016–17) offers brief eyefuls of its main subject matter—the migrant camp in Calais, France, known as the “Jungle,” which was “liquidated” in October 2016. We see the artist’s hands pulling back tent flaps, his boots kicking abandoned makeshift kitchens: then we see Żmijewski posing with an African refugee in Paris, or in Berlin’s Tempelhof Airport, cattily demonstrating to him how to use a broom, or painting his face white. The film is treated to look aged, flickering steadily and mixing effects such as light leaks, film flashes, and black leader. Through its antiquated appearance, along with, for example, shots of an X painted on the back of a wool coat, Glimpse alludes to the early footage of just-liberated Nazi concentration camps. With its footage of the artist’s intervening body, Glimpse also calls up the work of the postwar ethnographer-filmmaker Jean Rouch. In films such as Moi, un noir (1958)—realized collaboratively with denizens of an Abidjan (Ivory Coast) shantytown—Rouch co-created “ethnofictions” that also framed his own authorial position. In other words, Glimpse, like Moi, un noir is invested in how the filmmaker sees himself—not just “the other.” If it thus seems to set up the “artist as ethnographer” trope, Glimpse does so in a singularly pessimistic way: the white European only ever explores either techniques of integration and erasure or the scene of encounter with that other as a scene of self-discovery. This, in conjunction with the film’s self-conscious echo of 1945’s “discoveries,” suggests that even the Holocaust has become part of (white) Europe’s journey of self-revelation. And that too is a theme that repeats across a number of Documenta 14’s interventions, including Roee Rosen’s Live and Die as Eva Braun (1995–97), in the Benaki Annex in Athens, which uses black-and-white text and drawings to create a pretend-virtual-reality experience of Braun’s last moments and afterlife. Like Glimpse, Rosen’s work takes up that anchoring point in Europe’s autobiography only to twist it into an opportunity not to “remember” but to underline the narcissism and even erotic arousal of doing just that. Dystopian in the extreme, these are works for a world far from Documenta’s origins in Germany’s project of postwar self-reconstruction, and they suggest—or rather, assert—that there is no going back.

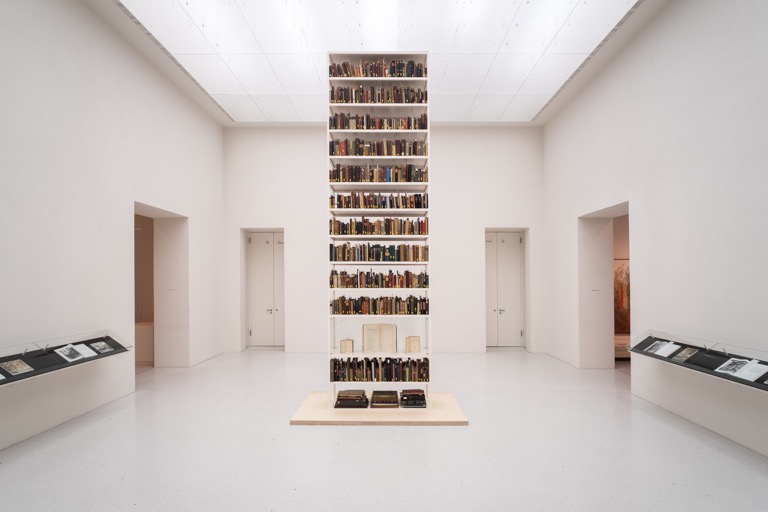

Maria Eichhorn, Unlawfully acquired books from Jewish ownership, 2017. Installation view. Neue Galerie, Kassel. © Maria Eichhorn/VG Bild-Kunst. Photo: Mathias Völzke.

If none of these works were installed with the kind of spectacularizing verve that we have seen in previous Documentas, that is not to say that spectacle is altogether absent from this edition. Marta Minujín’s The Parthenon of Books, a grotesque pillared structure binding various editions of banned books to a steel scaffold with plastic sheeting in front of Kassel’s Fridericianum, is portentous and off-putting. By making these books unreadable again—this time as part of an edifice mimicking a structure so key to Western democracy’s self-image—Minujín created the kind of massive one-liner that gives mega-exhibits a bad name. Differently imposing though no less vexing is Maria Eichhorn’s enormous, multi-part installation on the Nazi confiscation of artwork (in particular the infamous Gurlitt case, in which an official Nazi art dealer established an incredible collection of avant-garde art and managed to pass it along to his son). Eichhorn’s work not only takes up an enormous amount of physical space: it also invades one’s sense of all neighboring works, many of which continue the same themes. Some play on the formal means of “remembering” a stolen painting (David Schutter) and others subvert Eichhorn’s mode of pedagogical didacticism by inserting it into explicitly colonial frameworks (Pélagie Gbaguidi). But none deserve contamination by Eichhorn’s peculiar equation between, on the one hand, restitution and memory and, on the other, property rights and their place in the art world. In a Europe focused on the incredible damage wrought by neoliberal privatization as well as socialist collectivization, such a reductive premise seems to glide righteously past its own ramifications.

Beau Dick, installation view, documenta Halle, Kassel. Photo: Roman März.

While many such works remain fixated on Europe’s primal scenes, others seem inspired by the idea of Athens as a jumping-off point to discover or reexamine how artists function under the still-tight imperial yokes of the Euro-American hegemons. Over the last three and a half decades, until his untimely death this year, Beau Dick created a series of remarkable masks and figures, which dominated the entryway to Kassel’s Documenta Halle as well as the EMST in Athens. These glowering, hieratic totems, composed from materials ranging from cedar to acrylic paint to plastic action figures and fake feathers, not only demonstrate the skill and originality of this master carver, they allude to his role as a hereditary chief of the Kwakwaka’wakw, in the Pacific Northwest. Just as an expanded notion of history painting is on fulsome display in works by Tshibumba and Hila, among others, Dick’s sculptures alert the non-Kwakwaka’wakw to histories that are told “sculpturally” only insofar as that medium is part of another system of history-telling. These sculptures and masks testify to performances that will remain largely if not totally unseen by non-Kwakwaka’wakw audiences. And yet—or perhaps especially—so far from their place of origin and use, these are works that provide the score not only of one particular history but suggest the possibility of other modes of making and relating history altogether.

Lala Rukh, posters, flyers, screenprinting manual, and other materials relating to the Women’s Action Forum, Lahore (1980s–90s) . Installation view. Documenta Halle, Kassel. Photo: Fred Dott.

If it sounds as if all that this viewer could bring herself to see at Documenta 14 was history, that could be a professional predilection, or it could be that Szymczyk and his curatorial team, even at an exhibition mandated to show the contemporary, truly did want to foreground the historical, as experience. Take, for example, Maria Lai (1919–2013), a Sardinian artist whose watercolors, textile works, hand-painted photographs, and sculptures of bread dough and string were counterparts to her social sculptures and public actions. Or Lala Rukh (b. 1948, Lahore, who just died last month), a forty-year veteran of the Women’s Action Forum who made elegant propaganda posters and flyers, calendars, and screen-printing manuals alongside more contemporary video and photographic works. Both artists remind viewers at this Documenta that lengthy artistic careers could build force that is both aesthetic and political. Framing artists as bearers of cumulative historical experience by showing decades of each artist’s production rather than singular, spectacular works whose authors then become mere “stars”—and Lai and Rukh, like Hila and Dick, are only a few of the artists shown in this way—Szymczyk and his team stress the need for a new approach to authorship. Moreover, echoing across didactics-poor galleries, such a strategy makes room for an experience that would not rely on the kind of explanatory data so often considered necessary to “political” art.

In this way, history is continually introduced in the extended body of an artist’s work, rather than through signal pieces selected for their showstopper qualities. In some sense, this is the exhibit’s most provocative complication of a highly European notion of artistic authorship: rather than highlighting the author’s genius by showing her standout work—and thereby obscuring its relationship to her experience as a historical agent—it allows a more complicated set of relations between artist and society to emerge. Showing decades of production (and often collaboration) emphasizes the relevance of these relations in a manner that might make the show feel too “archival” for some audiences, but effectively shifts the burden of understanding away from didactics and toward other modes of spectatorship—perhaps still to be discovered.

And indeed, it was precisely in order to draw out the complexity of artists’ relations to society that the curators also organized what they called a “Parliament of Bodies”—discursive spaces that include live forums, radio broadcasts, film screenings, and communal performances. While a “parliament of bodies” might play on democracy’s Greek origins, as Documenta 14 makes clear again and again, even an enlightened team of international art curators can’t resolve what is unresolvable about democracy, including the politics of representation. Take, for example, the accusations of hypocrisy leveled at the curators and even some of the artists by LGBTQ activists, animal-rights activists, and Artists Against Evictions, who complained in April of the curators’ silence in the face of government arrests of squatting artists and refugees in two Athenian neighborhoods. Did Szymczyk or any of the curators ever respond—or perhaps more importantly, do we even know what an appropriate response might have been? Like the various graffiti across Athens (e.g., “Fuck Documenta” written over Documenta posters), such accusations and invectives at least force audiences (and non-audiences) to try to imagine how an art exhibit might usefully respond to such issues or to live protests. In this era of endless Internet quibbles, it is almost cleansing to have such open-ended, perhaps unresolvable debate. Documenta certainly advances its own political propositions, but one can also consider the public spaces for resistance that it constructed, built over, or failed to generate as further propositions, co-authored with a sometimes unwilling public.

Benjamin Patterson, When Elephants Fight, It Is the Frogs That Suffer, 2016–17. Sonic graffiti, 16-channel sound installation, Byzantine and Christian Museum (Gardens), Athens. Photo: Freddie F.

It is therefore perhaps fitting that one of the exhibit’s most successful pieces is a mere proposition in the sense that it was hatched by Benjamin Patterson, an African-American Fluxus artist who died before he could himself execute it. His gorgeous and hilarious sound installation When Elephants Fight, It Is the Frogs That Suffer (2016–17) was finished posthumously and invisibly secreted into the bushes and lilies of the gardens of Athens’ Byzantine and Christian Museum. There, When Elephants Fight interjects often silly choruses (“Oh we are the musical frogs / who live in the marshes and bogs”) into rocking pretend-frog sounds (humans imitating, often slowing down and thereby magnifying, the animal sounds) and real-frog symphonies. The piece riffs on his earlier Pond (1962), in which participants set mechanical frogs to hop across a floor-drawn grid, as well as Aristophanes’s The Frogs, which smuggles political messages into a play that uses aesthetic competition to resolve the political fate of the Athenians. If in Aristophanes’s play, a comedic approach accentuates the seriousness of the political stakes, in Patterson’s work it is the setting—current-day Athens, where the stakes are painfully high—that lends the comedic competition between human and frog a sense of distant but epochal weight. Documenta 14 works similarly, to distribute the political weightiness of art works across the exhibit as a whole. The art shown is itself—like The Frogs—far from apolitical, but it does not often carry its politics with the kind of righteous didacticism associated with “political art.” That didacticism—that forcefulness and directness—is reserved, in the end, for the framework of Europe as a whole, offered up as a cadaver, but a worthy target still.

Rachel Haidu is an associate professor in the Department of Art and Art History and director of the Graduate Program in Visual and Cultural Studies at the University of Rochester. She is the author of The Absence of Work: Marcel Broodthaers 1964–1976 (MIT Press/October Books, 2010) and numerous essays, most recently on the works of Ulrike Müller, Andrzej Wróblewski, Yvonne Rainer, Sharon Hayes, James Coleman, Gerhard Richter, and Sol LeWitt. Her current book manuscript examines notions of selfhood that develop in contemporary artists’ films and video, dance, and painting.