Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

In Todd Haynes’s documentary, a limited view of the noted band.

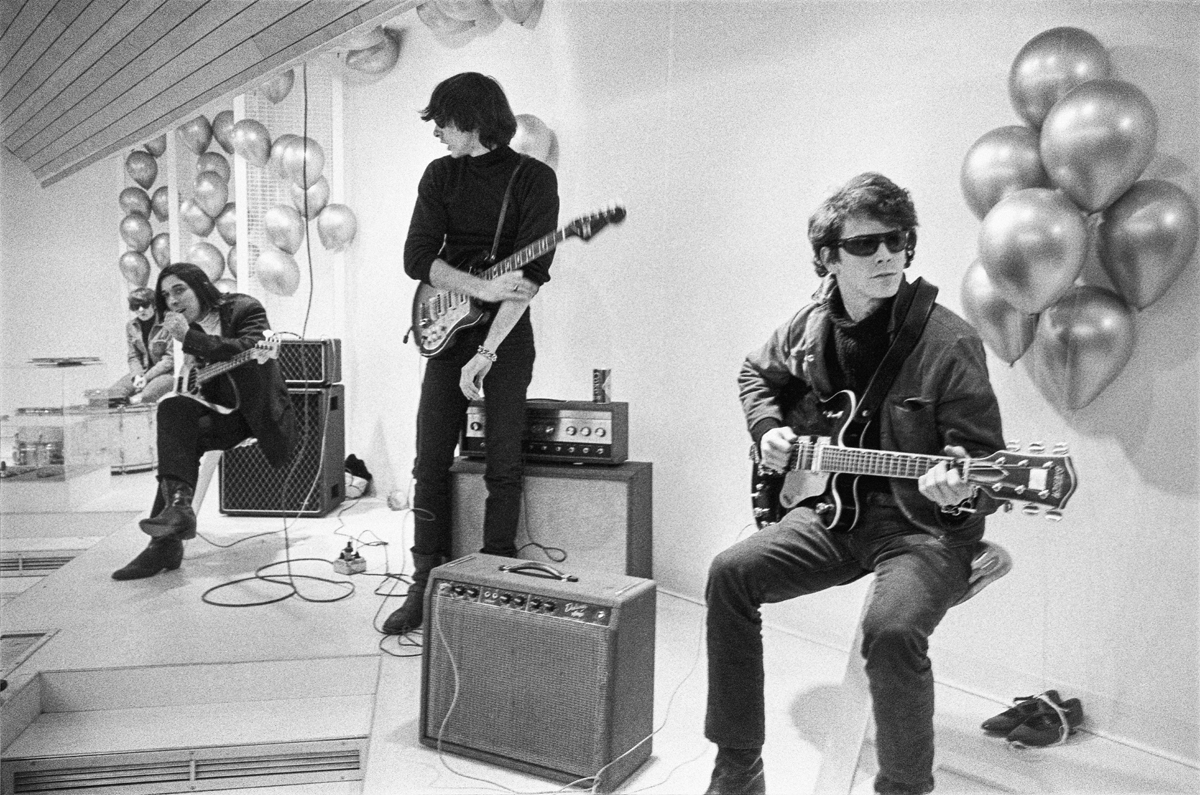

Moe Tucker, John Cale, Sterling Morrison, and Lou Reed, from archival photography from The Velvet Underground. Courtesy Apple TV+.

The Velvet Underground, directed by Todd Haynes, in theaters and streaming on Apple TV+

• • •

As renowned as the Velvet Underground are as a band, something about them still feels deeply mysterious, nearly sixty years after their inception in 1964. Very little footage of the group exists, especially compared to other famous rock bands from the 1960s, such as the Rolling Stones and the Beatles, whose performances were extensively documented.

But the Velvets weren’t the Rolling Stones or the Beatles; to this day, finding them on a classic-rock radio station is a bit of an oddity. They dealt with dark, transgressive subject matter, and while they had many sweet melodies, they weren’t afraid to verge on the unlistenable, with extended dirges and long cacophonous passages. They mostly labored outside the musical mainstream, and did not have great financial success over their relatively brief lifetime.

Todd Haynes has made several films dealing with music, but The Velvet Underground, a grandiose monument to the group released for Apple TV+, is his first documentary. He takes a sideways route to his subject matter here, as he has done with all of his music movies—whether it’s telling a tragic story with Barbie dolls (Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, released in 1987); creating a glam rock biopic modeled on David Bowie, without Bowie’s involvement or approval (Velvet Goldmine, 1998); or exploring Bob Dylan’s life and psyche in a nonlinear narrative, refracted through six different actors and actresses who all play him (I’m Not There, 2007).

John Cale, Sterling Morrison, and Lou Reed, from archival photography from The Velvet Underground. Courtesy Apple TV+.

In The Velvet Underground, Haynes dispenses with many of the usual documentary conventions, in part out of necessity. One obvious hurdle was that several central members of the band could not be interviewed because they have long since passed away (Nico died in 1988, Sterling Morrison in 1995, and Lou Reed in 2013.) Copious archival photos, footage, and interviews were used to fill in the gaps. (The documentary does include extensive new interviews with former band members John Cale and Maureen “Moe” Tucker.)

Another limitation was self-imposed: Haynes did not interview any current figures to provide commentary on the band’s legacy (say, by talking to music critics or younger musicians). He opted instead to only talk to people who were there at the time. The movie showcases new conversations with a wide range of fabulous personalities active in the 1960s, including the rock manager and publicist Danny Fields, actress and Warhol Factory icon Mary Woronov, film critic Amy Taubin, and the artist and filmmaker Jonas Mekas (who passed away in 2019). While it’s a refreshing strategy compared to most music documentaries, which tend to be formulaic, it also means that the movie lacks some useful distance. For instance, the composer La Monte Young says in the film that he was the first to create music with long sustained tones, but several non-Western musical traditions have dealt with long sustained tones for centuries, if not millennia, and no one is there in the movie to provide a dissenting opinion. A further issue is that everyone featured in the film is white; bringing in new voices could have added some needed diversity. The Velvets’ inspirations included jazz by Black musicians—Reed loved jazz—and their drones were inspired by experimental composers including Young, who were in turn inspired by Indian classical music.

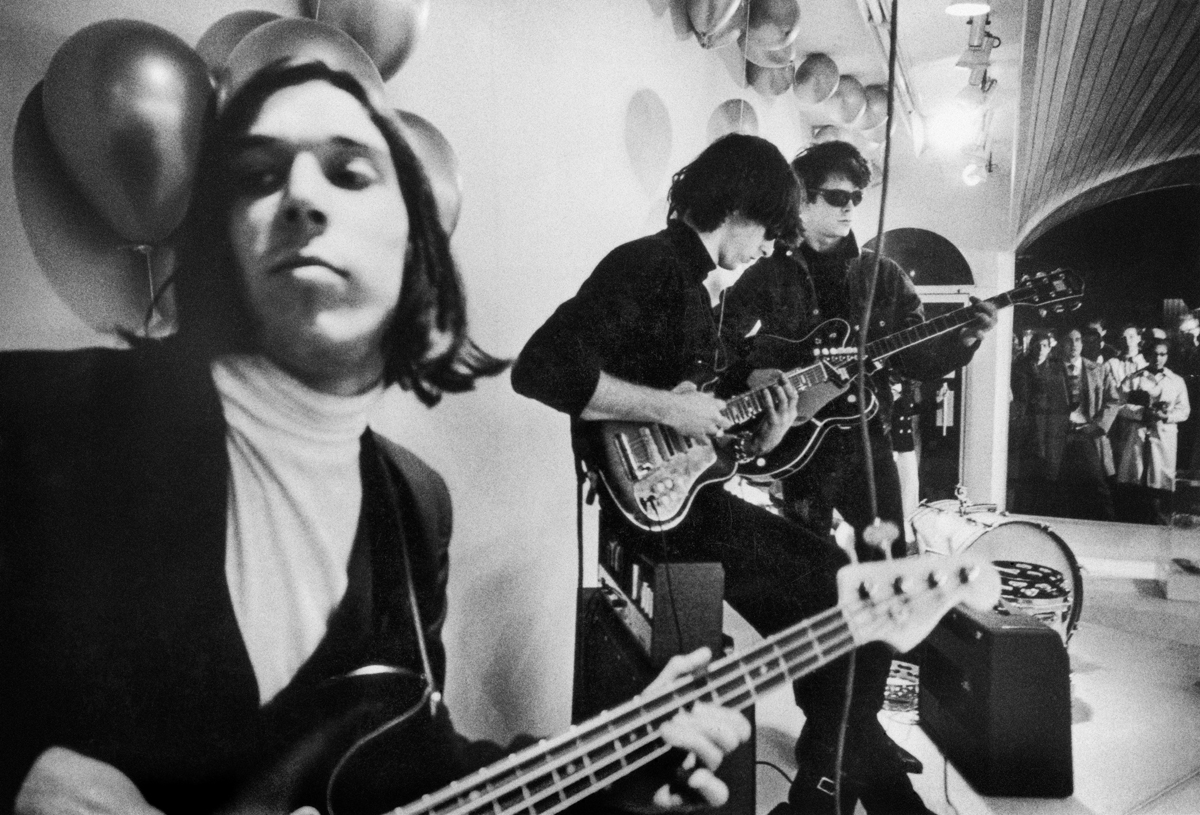

Paul Morrissey, Andy Warhol, Lou Reed, and Moe Tucker, from archival photography from The Velvet Underground. Courtesy Apple TV+.

Since there is very little footage of the band performing together—another obstacle Haynes faced—he relied heavily on the voluminous output of the Velvets’ erstwhile manager Andy Warhol. Haynes includes, among other things, footage from the Factory, many of Warhol’s iconic films of the time (including Sleep, Kiss, and Empire), and Warhol’s screen tests of the band’s members and friends. Haynes also pulls clips from many famous pieces of experimental cinema, such as Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid’s Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), John Whitney’s Catalog (1961), Stan Vanderbeek’s Poemfield No. 2 (1962), Shirley Clarke’s Bridges-Go-Round (1958), and Oskar Fischinger’s Spirals (1926). He uses snippets from them in tiled mosaic patterns, filling the screen with a kaleidoscopic head rush of moving images. The contrasting colors, graphics, and vintage imagery look glorious and impressive, particularly on a big screen, but it often feels like eye candy that has little to do with the band. For one, many of these works were made well before the Velvets were founded, sometimes decades earlier. And while the clips certainly look cool stacked side by side in elaborate formations, especially paired with a pounding Velvet Underground soundtrack, the fragmentary presentation detracts from the power of the short films themselves. To me, these works are individual pieces meant to be experienced in full, and some did not contain sound in their original design. While the psychedelic sensory overload may have been meant to simulate the colorful performances and light shows of the time, as well as, of course, Warhol’s “Exploding Plastic Inevitable”—in which images and patterns were projected onto the Velvets in a multimedia extravaganza—it just seems distracting in this context.

Archival split-screen frames from The Velvet Underground. Courtesy Apple TV+.

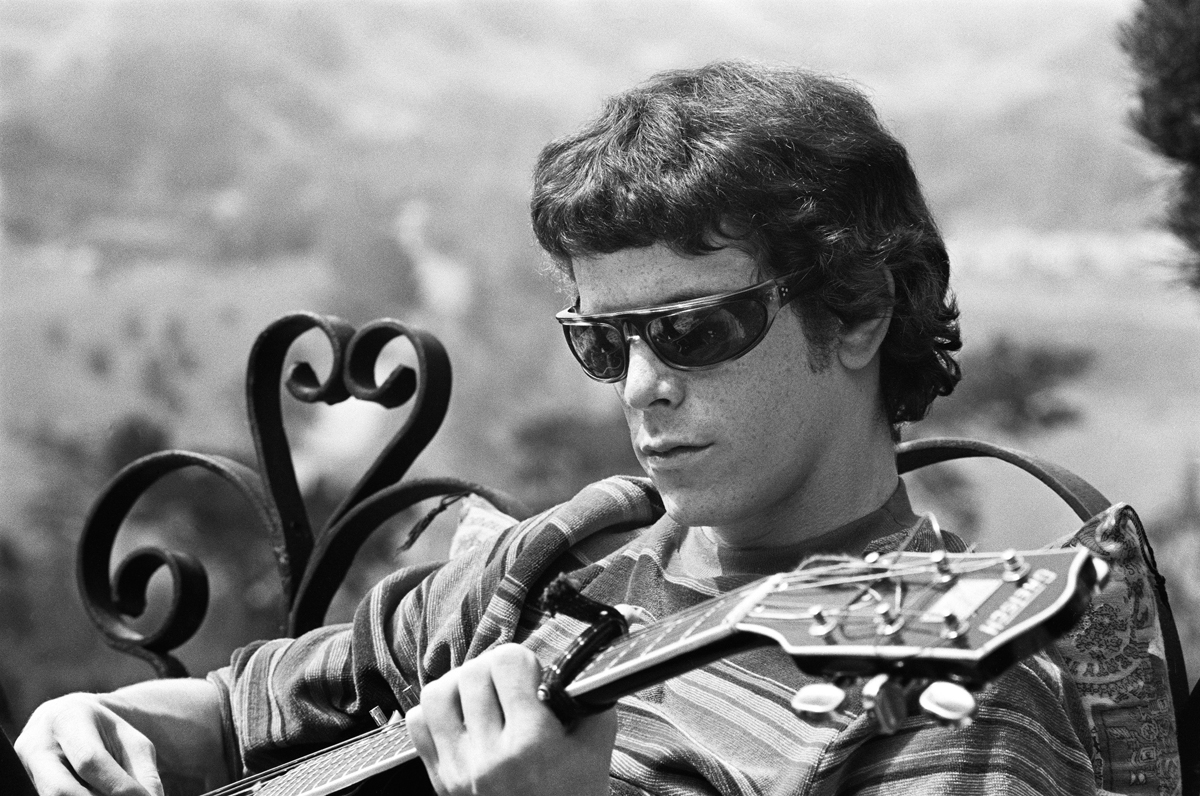

This hazy maelstrom of dreamlike imagery can also be reductive to those so often reduced, such as Nico, who has frequently been portrayed as a gauzy, enigmatic chanteuse. In the brief segment where she is discussed here, the film doesn’t do much to dispel that notion, and few specifics are divulged about her unique capacities as a musician—not only did she have a singularly melancholy voice, but she was a unique performer and a formidable songwriter. Some people are left out, such as the late Angus MacLise, the Velvets’ first drummer. Reed, meanwhile, completely dominates, even in his physical absence. There are so many moments in which other people could have been explored, but instead we are treated, for instance, to slow-motion footage of Reed eating a Hershey’s chocolate bar.

Lou Reed from archival photography from The Velvet Underground. Courtesy Apple TV+.

As the group has long been for many critics, the Velvet Underground is my favorite rock band—a deep love that began twenty-five years ago, when I was a student at MIT and happened on my first Velvets album at Newbury Comics in the college’s student center. The record was an acquired taste at first, but from then on, I memorized the group’s every song, every album, every rough demo.

Like Bowie, who also has yet to receive a truly great documentary that encompasses the total arc of his career, there is something about the Velvets that still defies interpretation. It is difficult to wrap the complexity of this band into any kind of neat package. By the end of The Velvet Underground, I was left with the same empty feeling I had when I saw Velvet Goldmine in a theater in 1998—the sensation that I had just seen a lot of flashy images and music without the connective tissue of real storytelling. Those who are already immersed in the Velvet Underground’s history and music will not learn much here that is new. But Haynes’s glossy documentary will hopefully pave the way for more movies on the band, because there is still more to unravel. The band’s enduring mystery is part of their lasting power.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.