David Deitcher

David Deitcher

Black life, black bodies, and a new art history at the Met Breuer.

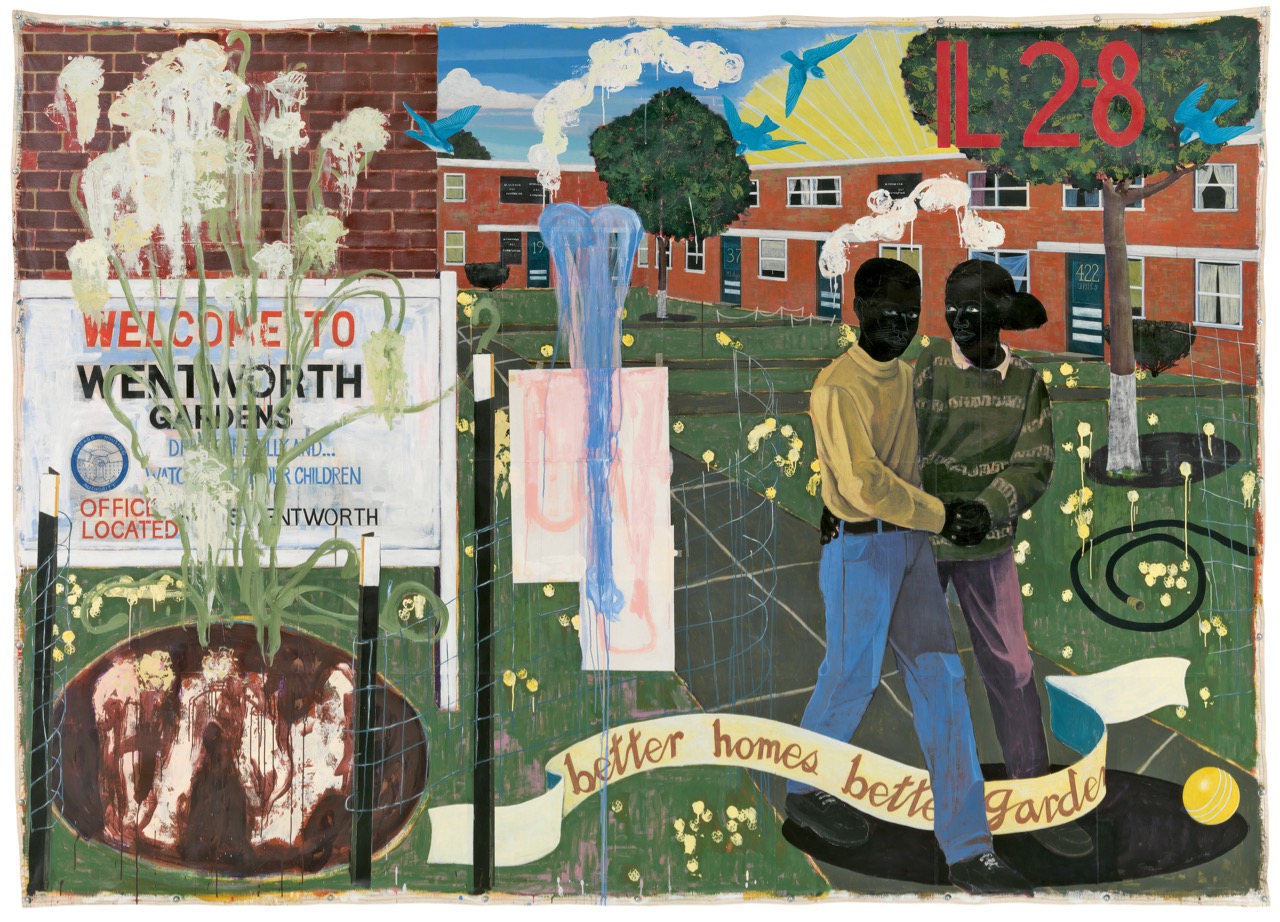

Kerry James Marshall, Better Homes, Better Gardens, 1994. Acrylic and collage on canvas, 8 feet 4 inches × 11 feet 10 inches. Image courtesy Kerry James Marshall and the Denver Art Museum.

Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, The Met Breuer, 945 Madison Avenue, New York, through January 29, 2017

• • •

“Mastry”—the subtitle of Kerry James Marshall’s sweeping survey now on view at the Met Breuer—is a disrespectful deformation of “mastery,” a word with painful connotations for anyone descended from slaves, and perhaps especially so for the African-American Marshall, who not only engages the “great masters” of painting but who arguably is one himself. In addressing “black modernism” and the Harlem Renaissance, literary scholar Houston Baker noted the correspondence between the “deformation of mastery” and the “mastery of form”—a dynamic that could also be applied today to Marshall’s modus operandi.

For three decades, Marshall has developed extraordinary technical skills, and since childhood has been immersed in art history; more specifically, in the tradition of painting that runs from the Renaissance’s celebration of the classical ideal through the historical allegories of the Enlightenment and impressionism’s depictions of the everyday life of a nascent middle-class. German artist Gerhard Richter once referred to that tradition as “the vast, great, rich culture of painting . . . that we have lost, but which places obligations on us.” For Richter this loss resulted mostly from modernist self-criticality, the progressive stripping away of representational complexity from painting. That celebrated tradition was differently lost to Marshall, who confronted the near total absence of black bodies and faces like his from this most revered of image archives.

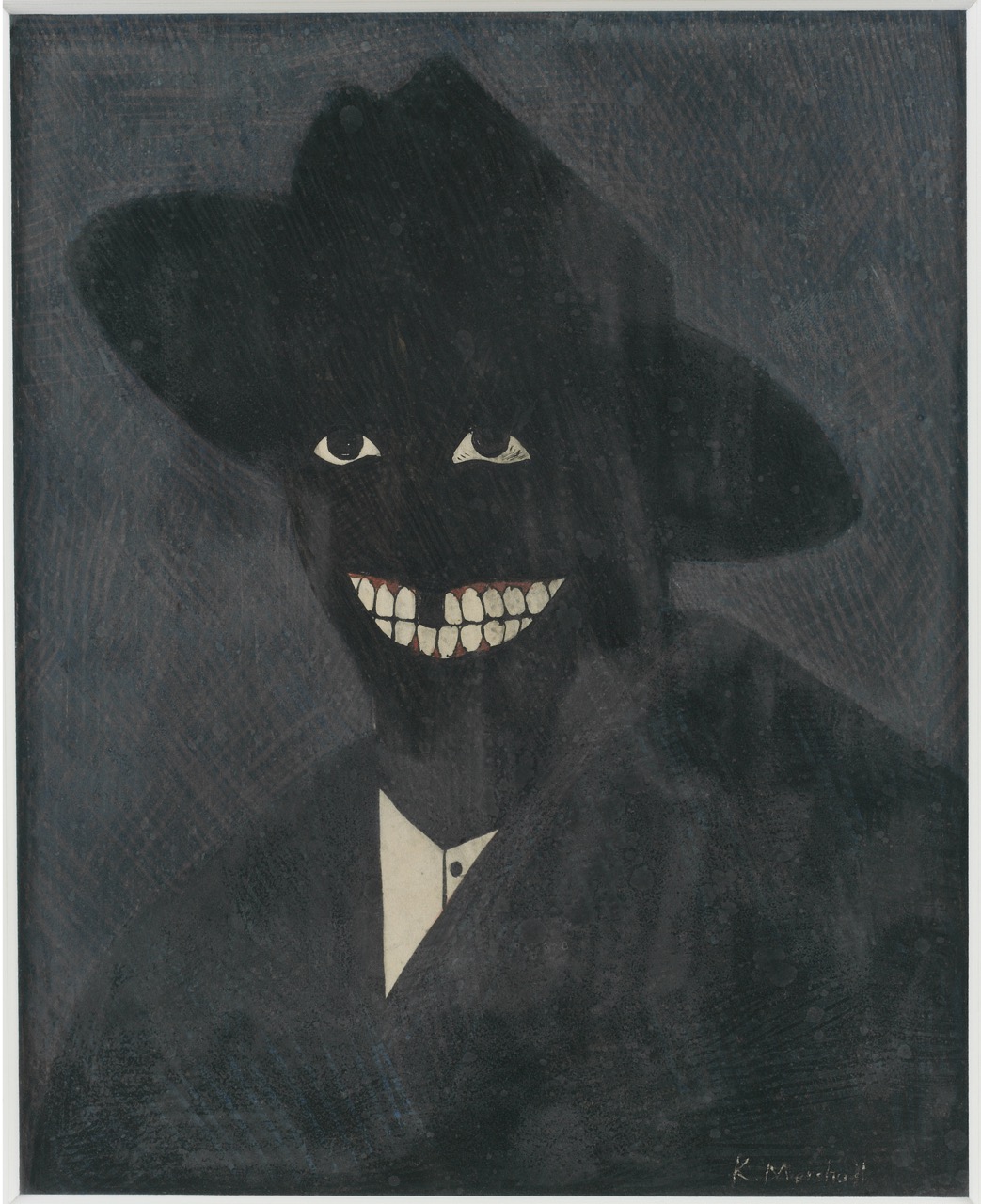

Kerry James Marshall, A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, 1980. Egg tempera on paper, 8 × 6 1/2 inches. Image courtesy Kerry James Marshall and the MCA Chicago. Photo: Matthew Fried.

“Mastry” could be imagined as an aggressive distortion coined by the protagonist of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, the 1952 novel that inspired some of Marshall’s earliest and still most affecting works. For example, A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self (1980), among the many moving paintings in the show’s first gallery. It is a black-on-black work on paper that autobiographically reiterates—exaggerating to the point of undermining—the racist stereotype according to which only the whites of a black person’s eyes and teeth show up in the dark. Notwithstanding its modest scale and paper support, this portrait demonstrates Marshall’s determination to participate fully within the exclusionary arena of high art as he resuscitates for this work the venerable but vastly outmoded technique of egg tempera. Employed in the early Renaissance prior to the common use of oil paint, egg tempera depicts forms with a velvety flatness that here enables Marshall to create a dialogue between the cruel cartoon cliché of the black figure and the icons of Christianity that egg tempera typically rendered—as unexpected an achievement as it is astounding for being so fully realized in visual and sensual terms.

Kerry James Marshall, De Style, 1993. Acrylic and collage on canvas, 8 feet 8 inches × 10 feet 2 inches. Image courtesy Kerry James Marshall and Museum Associates / LACMA.

It is widely understood that Marshall set out to rectify the absence of black bodies in art history. Take, for example, De Style (1993), its title a riff on the modernist Dutch movement De Stijl. This painting revives, as it radically revises, the antiquated genre of interiors rich in lively detail, such as the taverns painted by the seventeenth-century Dutch master David Teniers the Younger. Here Marshall lovingly pictures a barbershop interior as a center of black civic life, its rearmost plane a mirror adapted from Manet’s Bar at the Folies Bergère (1882). This mirror reverses the shop’s name in the window that gives onto the street and doubles the wealth of observed objects inside, along with the “style guide” (haircuts for customers to choose from) and the framed photograph of a boxer’s legs that both hang on the wall behind us, this last a variation on the trapeze artist’s legs that appear in a similar location in Manet’s painting. The mirror also serves as receptive surface for collaged and/or painted matter, including the framed “MASTERS CERTIFICATION” for this, “PERCY’S HOUSE OF STYLE.”

But Marshall’s works do more than appropriate from Western art history. He has portrayed fictional black artists, reflected on black romance, evoked the pain of realizing how racially stacked the decks have been in cultural constructions of human beauty, and recalled significant events in black history. During the early 1980s, when Marshall created the earliest works in this survey, some critics declared painting dead, yet again. One remarkable effect of his endeavor has been a revitalization of painting itself as an ethical, representationally complex, intensely relevant, arguably even necessary art form. The show at the Met Breuer makes plain that Marshall has accomplished all this as convincingly as Richter’s altogether different rehabilitative method, which put painting’s stylistic rhetoric under erasure.

One highlight of the exhibition is the installation on the Met Breuer’s fourth-floor landing of all nine works that constitute or relate to Marshall’s magisterial Garden Project paintings (1994–97), seen here for the first time together since their legendary debut at Documenta X in 1997. These monumental pictures critically reconsider the social promise and ultimate failure of postwar housing projects such as those that the young Marshall and his family called home, first in Birmingham, then in the Watts section of Los Angeles. “We think of projects as places of despair,” Marshall has said. “All we hear of is the incredible poverty, abuse, violence, and misery that exists there, but there is also a great deal of hopefulness, joy, pleasure, and fun.”

Kerry James Marshall, Many Mansions, 1994. Acrylic and collage on canvas, 9 feet 6 inches × 11 feet 3 inches. Image courtesy Kerry James Marshall and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Pleasure and fun are abundantly present in some Garden Project paintings. Many Mansions (1994) shows three young black men in black trousers, white dress shirts, and narrow ties gardening with the projects looming as backdrop, all under a sinuous red ribbon that paraphrases the Book of John: “IN MY MOTHER’S HOUSE THERE ARE MANY MANSIONS.” A gardener is pictured resting on one arm in an evocation of the first- or second-century AD Roman sculpture The Dying Gaul. Marshall limns his crystalline profile to convey classical beauty as black. The artist juxtaposes the men’s labor with more conventional signs of “joy, pleasure, and fun”: two cellophane-wrapped and beribboned Easter baskets brimming with teddy bears and Easter bunnies. In the foreground of Untitled (Altgeld Gardens) (1995), for neither the first nor the last time, Marshall invokes synesthesia on a warm afternoon. Emanating from the speakers of a boom box at lower right are painted musical notes and lyrics from Ruby and the Romantics’ wistful 1963 hit single: “Our day will come . . . and we’ll have everything.”

In a tragic irony, even as Marshall began his cycle of paintings that reimagine such housing projects as Chicago’s Ida B. Wells Homes, Robert Taylor Homes, and Rockwell Gardens as romantic idylls, in 1995 the proliferation of gang violence, drugs, and crime led the US Department of Housing and Urban Development to take over that city housing authority’s projects, which they soon decided to demolish. Marshall has painted black life in the United States as it has been and still is lived, both physically and emotionally. He also has pictured its amelioration, thereby bringing to mind bell hooks’s insistence that art should not only tell it like it is but imagine the way things can be.

Born in Montreal, Canada, David Deitcher is an art historian and critic whose essays have appeared in Artforum, Art in America, Parkett, The Village Voice, as well as in anthologies and monographs on such artists as Sherrie Levine, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Isaac Julien, and Wolfgang Tillmans. He is the author of Stones Throw (Secretary Press, 2016) and Dear Friends: American Photographs of Men Together, 1840–1918 (Abrams, 2001). Since 2003, he has been core faculty at the ICP/Bard College Program in Advanced Photographic Studies. He lives in New York City.