Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

A new biography of England’s most famous opium-eater.

Guilty Thing: A Life of Thomas De Quincey, by Frances Wilson, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 397 pages, $30

• • •

In the Romantic essayist Thomas De Quincey’s work and life—he was born in 1785, and died aged seventy-four—the contradictions were deeply rooted and little resisted. He was a freelance magazine writer with sublime literary ambitions, a ragged-trousered Tory snob, a deadline-surfing sluggard whose complete works nonetheless run to twenty-one volumes. De Quincey wrote for around forty years, but his fame rested almost solely on his 1821 autobiography of sorts, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. In that book, he contrived in elevated and digressive prose a type of personal essay that still feels inventive and candid. Saint Augustine and Jean-Jacques Rousseau had been there before him with their Confessions, but De Quincey invented the modern form of the memoir, in which the nature of the writing “I” itself is at issue.

De Quincey’s major works are notably attentive to architecture and interiors, both real and imaginary. Frances Wilson has taken his spatial preoccupations as a prompt to write a “De Quinceyan” biography. Guilty Thing follows him from the “pensive citadels” of student digs in Manchester and Oxford, through freezing hovels in London, to the Romantic idyll of Dove Cottage, which he took over from William Wordsworth and filled to bursting with books and papers. De Quincey was haunted by recollections of the rooms in which key events of his life had taken place: a sunlit bedroom where his dead sister lay, the Whispering Gallery at St. Paul’s Cathedral, where voices echoed like bad memories. In later life he had a habit of fleeing his shabby temporary dwellings, leaving only manuscripts in lieu of rent.

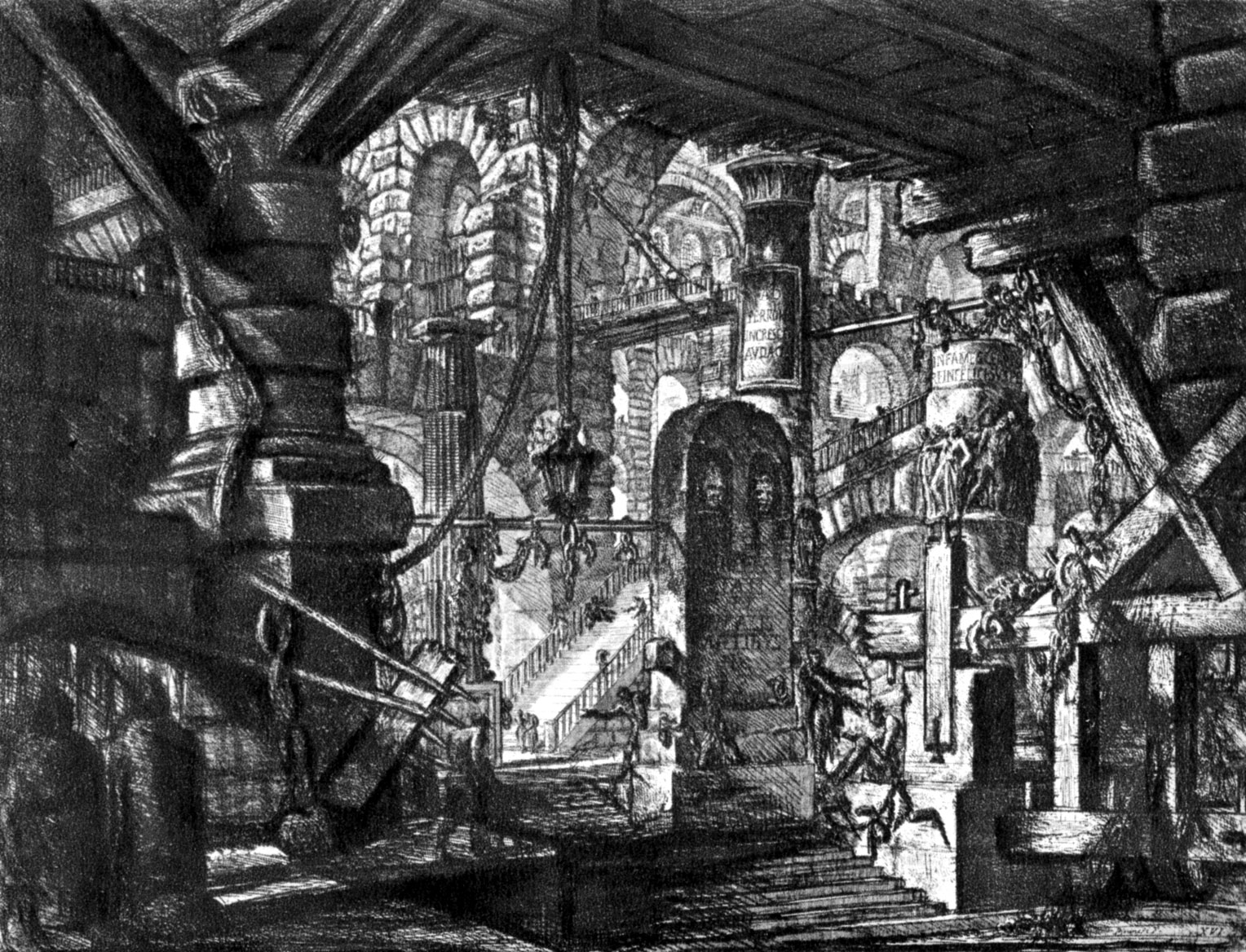

“Opium was the making of De Quincey,” writes Wilson, not without irony. According to Confessions, he began taking the drug in the autumn of 1804, after waking one day with rheumatic pains in his face. Opium was then legal and ubiquitous; it turned De Quincey into a dreamer, not a degenerate. Confessions soon expands to disclose the “tremendous scenery” unfolding before his opiated gaze: “a theatre seemed suddenly opened and lighted up within my brain, which presented nightly spectacles of more than earthly splendour.” There are visions of Egypt and China, crocodiles with cancerous kisses, labyrinthine prisons out of Piranesi. The word De Quincey liked to use about his dreams was “phantasmagoria,” and he seems to have thought about autobiography in the same terms. Confessions is a Gothic entertainment as much as unfeigned “life writing” or nascent addiction tale.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Untitled etching (called The Pier with Chains), plate XVI (of 16) from the series The Imaginary Prisons (Le Carceri d'Invenzione), Rome, 1761 edition (reworked from 1745). Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Calling himself “the Opium-Eater” or “X. Y. Z.,” De Quincey capitalized on the celebrity of his first book to become a regular (though always unreliable) contributor to literary magazines. Having followed his poetic heroes to the Lake District, he assumed the role of unofficial biographer to Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. (Out of envy, perhaps, he was remarkably vicious about both, revealing to his readers Coleridge’s own opium addiction and Wordsworth’s weak, unattractive physique.) Wilson is especially illuminating on the perplex of ambition, laziness, and anxiety in which De Quincey worked for the rest of his life, playing editors against each other as he turned in millions of words on myriad subjects: political economy, rhetoric, Shakespeare, German metaphysics, even amateur cosmology.

At the heart of all this chaotic industry was a conception of the essay—already a deeply personal form in the hands of Michel de Montaigne, Samuel Johnson, or Charles Lamb—wound to a Romantic pitch of subjectivity. Many decades before Freud, De Quincey insists that we cannot escape our own childhoods: “Of this at least, I feel assured, that there is no such thing as forgetting possible to the mind.” He was the first writer to use the word “subconscious,” insisting even at his most garrulous and self-revealing that his own character was obscure, “involuted,” hidden in a palimpsest of stories and experiences. It’s too easy to say that De Quincey is a precursor to the “narcissism” of today’s memoirists—the complex lesson of his autobiographical writings is that the subjective “I” tends to waver the more clearly we try to express it.

Having written about himself, De Quincey turned to everything else. As Wilson reminds us, his voracious curiosity was partly a matter of historical accident: he wrote at a time when the popular press was expanding greatly, and he took ample advantage of being paid by the page. He is the quintessential occasional essayist, who could work up an erudite reflection from the most fleeting and mundane material; in “The English Mail-Coach,” for example, he gives us one of the first and best accounts of a road-traffic accident. De Quincey’s prescient understanding of the essay is that it should be as capacious, vagrant, and original as the best fiction. As Virginia Woolf, who is one of the most obvious inheritors of his attitude, wrote: “He mocks; he dilates; he makes the very small very great. . . . Scenes come together under his hands like congregations of clouds.”

What he was emphatically not was a reporter. Wilson frames her biography with accounts of De Quincey’s interest in a series of murders along the Ratcliffe Highway in east London in 1811. At a stroke, in his essay “On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts,” he crystallized the related genres of true crime and the murder mystery. But he was writing at second hand, from the poetic solitude of Dove Cottage, and De Quincey could not help casting John Williams, the main suspect in the case, as a kind of Romantic hero. “On Murder,” like much of De Quincey’s output, might best be described by that irksome contemporary term “creative nonfiction.” His influence was felt throughout the nineteenth century: in Charles Dickens’s journalism, in the stories and essays of Edgar Allan Poe, in Charles Baudelaire’s very free translation of Confessions. At a moment when the memoir is well established and the essay now ascendant, his oddly generous form of self-absorption seems more engaging and instructive than ever.

Brian Dillon’s books include The Great Explosion (Penguin, 2015), Objects in This Mirror: Essays (Sternberg Press, 2014), The Hypochondriacs (Faber & Faber, 2009), and In the Dark Room (Penguin, 2005). He is UK editor of Cabinet magazine and teaches at the Royal College of Art, London. He is writing a book about essays and essayists.