Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Arsenic, ruins, and feral cattle: Cal Flyn treads forsaken landscapes.

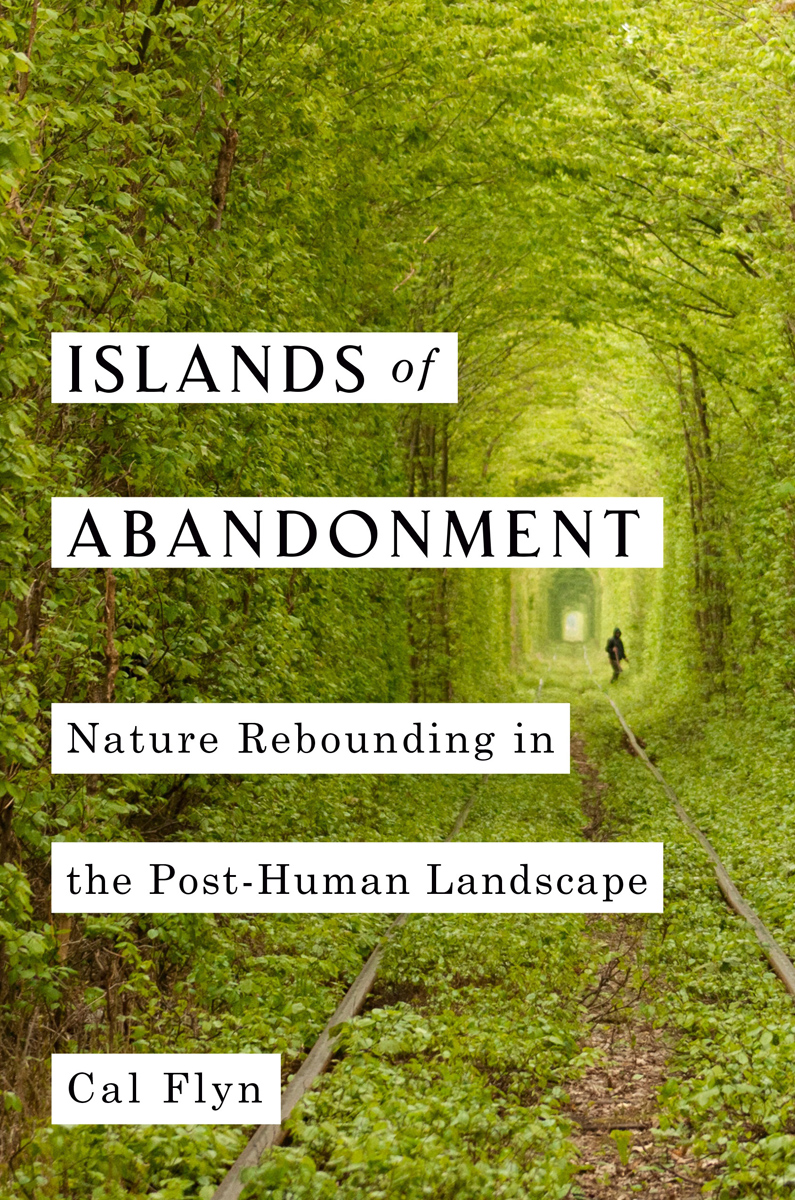

Islands of Abandonment: Nature Rebounding in the Post-Human Landscape, by Cal Flyn, Viking, 372 pages, $27

• • •

Nature is healing—it swiftly became a multipurpose joke of early-pandemic life online. But hadn’t there been a little truth in its first, unironic, deployments? Wild goats in the small-town streets of Llandudno in Wales; pumas lurking about an apartment complex in Santiago, Chile; kangaroos bouncing through the business district of Adelaide, Australia: it seemed in our absence that a kind of recovery was under way. As the Scottish writer Cal Flyn points out in Islands of Abandonment, no actual healing was going on, because there is no state of Edenic nature to go back to. These wild incursions were a glimpse, however, of something: the dialectic, half ruinous and half redemptive, that results when humans flee, neglect, or forget certain spaces. Flyn is an energetic guide to some of these dead sites and the futures they predict.

She has “spent two years traveling to places where the worst has already happened,” whether the catastrophe in question has been military, industrial, or (vexed term) natural. In West Lothian, Scotland, she climbs the Five Sisters Bing: a range of vast slag heaps created by an oil industry that thrived there from the 1860s to the 1920s. The mountains of burned shale have gradually, in a process of “primary succession,” turned fertile and life-supporting. As we also discover in Flyn’s visit to the militarized buffer zone between Greek and Turkish Cyprus, and her exploration of Chernobyl and its toxic environs, an astonishing wealth of quaintly named flora grows on the slopes of the Five Sisters. “Kidney vetch and toadflax, bluebells and plantain, yellow rattle, pearlwort, speedwell, sweet cicely.”

Such inventories alternate in Islands of Abandonment with intimate accounts of decay: the graying of window panes and softening of boards, the slow creep of moss and lichen, the way an abandoned building holds its own until the roof is breached and rain gets in—then it is doomed. In postindustrial Detroit (over-visited location for “ruin porn” in recent decades) and more widely in the US, the dereliction is called “blight.” Derived from the terminology of horticultural disease, it’s not a neutral word, but laden with implications of race and class that Flyn only briefly acknowledges when she says its use is “almost impossibly provocative.” Still, here in her book’s second part (of four) she is as much interested in the people she finds in these places—holdouts and squatters, opportunist combers of the wreckage—as she is exercised by the inhuman processes at work there. In the vacant mills of Paterson and Passaic, New Jersey, she meets loners and scavengers, the drug-damaged and homeless, eking a life at the blasted “ground zero of American capitalism.”

William Carlos Williams once called the polluted Passaic River “the vilest swillhole in all of Christendom.” In an essay for Artforum in 1967, Robert Smithson wrote that the banks of the river, bristling with pipes and derricks and highway construction, constituted a new “eternal city”—a field of modern ruins to rival the relics of classical Rome. Islands of Abandonment is picturesquely punctuated with the literature and art of rot and renewal. Flyn quotes T. S. Eliot in The Waste Land: “What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow / Out of this stony rubbish?” She notes that in 1975 the Conceptual artist John Latham proposed settling the question of what to do with the Five Sisters by simply designating the mounds as monuments or sculptures. And, inevitably, Flyn invokes the ruined but weirdly lush Zone in Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 film Stalker.

In her own imagery, and the rhythms of her prose, Flyn has to wrestle with a perennial problem in writing about ruins: all descriptions, no matter how diverse in time or place, tend to the same familiar slump, the same unhappy details. The temptation is to try and energize each example with new vocabulary, new metaphors, and new sensations. They don’t always come across. One finds oneself, like Flyn, reaching for gothic verbs and adjectives: “At every corner, where the unknown looms tenebrous and forbidding, I need to force myself forward.” Or you claim insights and intuitions that readers may not credit, as when Flyn visits a decrepit church in Detroit: “You can feel it in the air: the emotional trace of past epiphanies, crises of faith.” Really?

Islands of Abandonment is at its best when Flyn is describing dilapidated or reborn places where spectral anthropomorphism can get no purchase, where things are simply too inhuman. “If we want to do the best for the environment, what we need is a new way of seeing: a new way of looking at the land.” In Verdun, France, she travels to the Zone Rouge, where huge quantities of chemical weapons were dumped and blown up after the First World War. The resulting wasteland—one rather fears for Flyn as she steps into it—is “a world iced with arsenic and soaked in lead.” It’s a microcosmic vision of what the paleontologist Peter Ward has called the earth’s Medea tendency, the coming “death phase” before the life that succeeds us can begin. In an extraordinary final chapter, Flyn stands at the edge of California’s Salton Sea—shrunken, desiccated product of flooding and retreat in the last century—and contemplates a place become arid and sulfurous, “scoured by desert winds” that raise toxic dust.

“This should be a book of darkness, a litany of the worst places in the world.” And yet, Flyn insists, her book is “a story of redemption.” On the Scottish island of Swona, which was last inhabited in the 1970s, she sees (and keeps prudent distance from) a herd of cattle turned feral. Left to their own devices, the animals have developed complex hierarchies and rituals such as observed among elephants; they even seem to show some reverence toward their deceased fellows. Here, “abandoned” and “wild” don’t mean entropic or defunct—there is hope, just not for us.

Brian Dillon’s books include Suppose a Sentence, Essayism, and In the Dark Room. He is working on Affinities, a book about images.