Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Bodies turn into things, things turn into bodies: a collection of “autoscopic” stories reveal the unsettling oddness of youth.

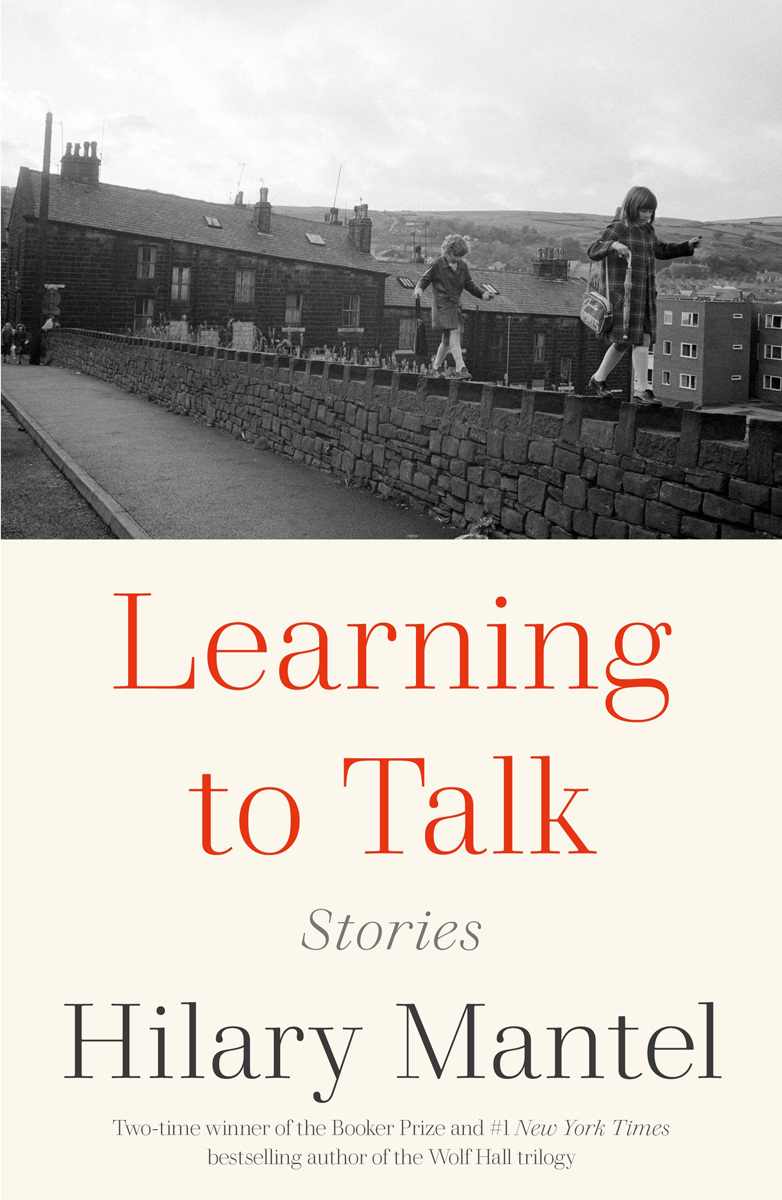

Learning to Talk: Stories, by Hilary Mantel,

Henry Holt, 157 pages, $19.99

• • •

How unexpected, how consoling, that one of the best-selling British novelists of recent decades should also be such a peculiar, stringent prose stylist—and gothic affronter of authority. Hilary Mantel is author of a celebrated trilogy of novels—beginning with Wolf Hall in 2009—about the life and career of sixteenth-century statesman Thomas Cromwell. Exactitude and luxury of detail in her historical fictions is allied to, or maybe vies with, a narrating voice both confidential and figuratively estranging. Outside of her novels, this style now and then gets Mantel into trouble. In 2013 in an essay about the royal family for the London Review of Books, she described Kate Middleton as “a jointed doll on which certain rags are hung.” Politicians lined up to condemn her, pretending not to see that Mantel’s image damned Britain’s polity and press rather than the future queen consort.

The stories in Learning to Talk—a collection first published in the UK in 2003—are mostly drawn from life. They are, says Mantel in a new preface, not so much autobiographical as autoscopic; she regards her youth from a sharpening distance. The stories’ protagonists share much with the author: born in a blackened mill town in the northern county of Derbyshire, raised Catholic, and nearing adolescence in the early 1960s. A strongly contained childhood, but with this unusual detail: “When I was about seven, my mother moved her lover into our house.” Gossip and isolation followed, a change of name and locale, maturing awareness of the necessity for and the costs of secrecy. A Jamesian question: How much does the child know? She recalls being surrounded by mother, lover, lover’s friend: “In that one moment it seemed to me that the world was blighted, and that every adult throat bubbled, like a garbage pail in August, with the syrup of rotting lies.”

Mantel evokes beautifully a place ingrained with the soot and sweat of labor, a time populated with racist landlords and “dental cripples,” when relatives were the only domestic visitors, and one’s parents seemed to have no actual friends. The 1960s have arrived, but they are assuredly going on elsewhere. No youthquake here: “There should be support groups, like a twelve-step program, for young people who hate being young.” In the title story she (or her near-fictional stand-in) attends elocution lessons, in order to rid herself of flat northern vowels—in advance of escape, and the ruefulness that comes with it. In “The Clean Slate,” the past lurks, dissolving, in the local memory of a village flooded for a reservoir. Mantel projects from the depths the image of a household at the moment of inundation, all fixtures and fittings suddenly awash, as if airborne. But it’s a fantasy: the village was demolished before flooding, and the waters anyway encroached with insidious slowness.

The drowned village is one of the larger conceits in Learning to Talk; usually, Mantel’s imagery is less allegorically freighted, less amenable. Her particular, unsettling skill lies in discovering queasy equivalents for physical sensations and emotional states—the body is always there, as metaphor, to remind us of its unmetaphorical heft and threat. In “Curved is the Line of Beauty,” two children are lost among the totemic rust-piles of a scrapyard. They have brought plums to sustain them on their excursion away from the domestic ménage, and the narrator tells us: “I carried my plum in my palm, caressing it, rolling it like a dispossessed eye.” Things turn into bodies under Mantel’s exactingly weird gaze, and bodies into things. Converse of the enucleated plum: in “Comma,” a story from her later collection The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher (not a title that endeared her any further to the British establishment), a disabled or disfigured child, seen from a distance by a young narrator, is pictured as a punctuation mark, faceless but full of meaning.

The innocent cruelty of childhood, youth’s horror at the alien predicaments of adult bodies and adult lives: Mantel conjures all this with nerveless precision. Nowhere more so than in “Third Floor Rising.” She is eighteen, and in the time between high school and university gets a job in Manchester, at a department store where her mother also works. The teenager is unprepared for life: “There was air in the spaces between my bones, smoke between my ribs.” The older women around her seem to this girl scarcely human: “a slowly rolling mass of flesh, fiercely corseted inside a dress of stretched black polyester . . . the skin with the murky sheen of carnation water two days old.” The most disturbing presence in this place, which also seems to be haunted, is a consignment of stinking sheepskin coats: “Herding them was heavy work; they exhaled with a grunt when they were touched, and jostled for lebensraum, puffing out their bulk and testing their bonds inch by squeaky inch.”

Such passages recur across Mantel’s fiction and nonfiction—what does she mean by them? Something to do with how flesh analogizes failing spirit, and vice versa. Learning to Talk ends with a singularly odd story, “Giving Up the Ghost,” that reads as if condensed from Mantel’s memoir of the same title, published in the same year, or as a review of sorts of that volume. Giving Up the Ghost (the book, that is) begins with the apparition of the author’s stepfather, Jack: or the ghost might be simply an artifact of recurrent migraine. The memoir goes on to describe years of ill health and chronic pain due to undiagnosed endometriosis. Sickness also haunts Learning to Talk: an intermittent presence in childhood, a horizon, perhaps, toward which everything is moving. It’s part of the wider project or tendency in Mantel’s work: to explore, as she does so lucidly and strangely here, the hinterland between emotional history and anxious embodiment.

Brian Dillon’s Essayism and Suppose a Sentence are published by New York Review Books. Affinities, a book mostly about photographs, will be published in spring 2023.