Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

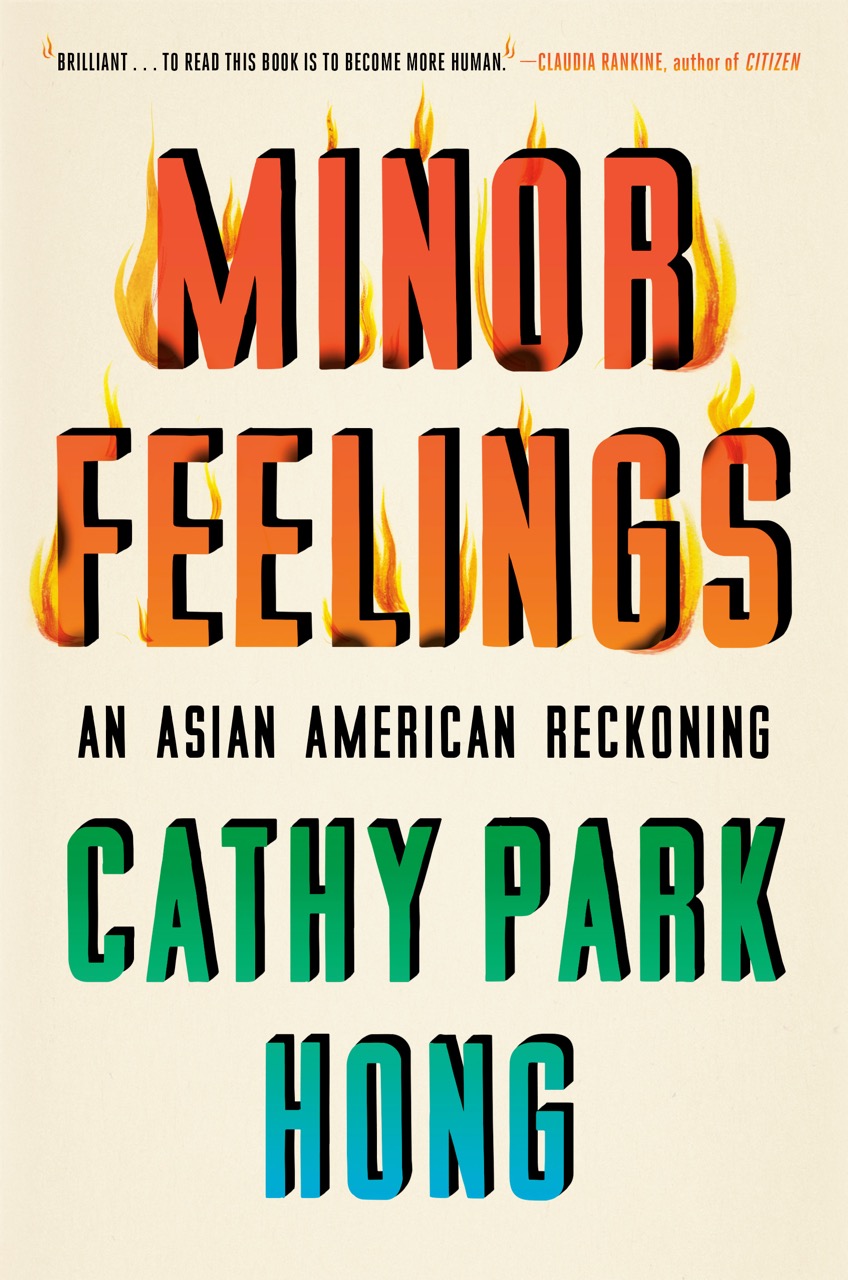

The poet Cathy Park Hong offers seven essays on the

Asian American condition.

Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning, by Cathy Park Hong,

One World, 224 pages, $27

• • •

In her celebrated book Ugly Feelings (2005), the critic and theorist Sianne Ngai gives a name and a history to those undistinguished emotions—irritation, envy, boredom, disgust—that modern art and literature have tended to prefer over sublimer affects. As the Korean American poet Cathy Park Hong notes in Minor Feelings, her furious suite of seven essays, the seemingly trivial passions are frequently involved with larger predicaments of politics and identity. Citing Ngai, she broaches “the racialized range of emotions that are negative, dysphoric, and therefore untelegenic, built from the sediments of everyday racial experience.” Hong’s poetry—in the collections Translating Mo’um, Dance Dance Revolution, and Engine Empire—is a slangy, code-switching, erudite medium that at its most energetic seems to promise a polyglot utopia. No such luck, we live in the dismal present. And Hong lives in America, where “I have struggled to prove myself into existence.”

To be Asian in the US, so racist cliché has it, is to be “next in line to be white”—or, as Hong puts it, next in line to disappear. “We have a content problem. They think we have no inner resources.” The erasure of Asian American experience takes diverse forms: from a racial designation as “Other” in surveys and polls, through widespread white ignorance of historical persecution and purges, to the very discourse that elevates one to the status of good immigrant, economic striver, happy example with which to upbraid African Americans. All of it, and much else in the way of small hostilities and large, is to blame for the abiding sense of shame that Hong details in the first three essays in Minor Feelings. Shame for her parents’ angry struggle, shame about her community’s racism toward others in her native LA, shame at her own eventual success in pleasing white readers with her poetry.

This last is more or less where Minor Feelings begins, with Hong poleaxed by a depression that manifests, on the opening pages, in a fear of the return of a facial tic she suffered in her twenties. This time, she has imagined the tic, but anxiety takes hold and reminds her of past disquiet. Despite her writing, in spite of her success, the poet is once again “the child who could not speak English.” A trip to perform a reading turns into a disaster: “It was a miracle I managed to board a plane when all I wanted to do was cut my face off.” In time, Hong claws her way back. She develops an obsession with the comedy of Richard Pryor, and finds herself devoting hours to transcribing his live performances. (Hong’s hilarious, protean poem “Notorious” borrows the trope of a terminally dull heaven for white people from Pryor’s 1979 Live in Concert film, and deposits rapper Notorious B.I.G. there: “Wrong ear-sucking heaven.”) She even starts to perform stand-up herself, in an effort to wreck her own and her audience’s expectations.

In the first half of Minor Feelings, Hong moves between her experience and a wider survey of Asian American history: from the anti-immigrant laws of a century ago to the savage treatment of Vietnamese American doctor David Dao, dragged unconscious from a United Airlines flight in April 2017. With an essay titled “An Education,” the book starts to sustain a more memoiristic, no less essential tone. Hong writes intimately about her education in fine art at Oberlin College, and about the other Asian American women who accompanied her, contended with her, became mired in a sort of wildly productive folie à trois. The names have been changed. Erin was a fearless Goth with East Coast ambitions when Hong was still unsure about her art and “might as well have worn a beret and smock.” Helen was bipolar, suicidal, obsessed with Eva Hesse, and raged in a way that recalled Hong to her own heavy-drinking father and violent mother. The description of young friends hothousing each other, artistically and intellectually, to the edge of disaster is brilliantly done, but it comes with a lesson about race and gender, half a paragraph from the end: “We had the confidence of white men, which was swiftly cut down after graduation, upon our separation.”

In the process, Hong discovered she was a poet and not an artist. “The lyric was the pure possibility of what my art could be if I had infinite resources to not merely build an object, but create a world.” Among the exemplars she found as a young writer was Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, the Korean American artist probably best known for her 1982 book Dictée. The formal range and daring of Cha’s writing—drawing together family history with the iconography of Joan of Arc and the Greek muses, moving abruptly between genres and languages—is one subject of Hong’s penultimate essay, “Portrait of an Artist.” Its other theme is the swift and then persistent forgetting of the facts of Cha’s death, aged thirty-one. Just days after Dictée was published, she was raped and murdered in New York. Why did her death not attract more press attention? Why do the scholars and curators who study and promote her work today still elide the details? Hong’s essay is at once homage, investigation (she speaks to Cha’s friends and family), and polemic against the obvious answers.

If Ngai inspired the title of Minor Feelings and its focus on the mundane interiorized nature of anti-Asian racism, Cha is one antecedent for another key term in the book. “Bad English” is what Hong calls her ravenous, engorged poetic style, in which different cultures, their languages or argots, all contend. Is it possible to concoct a bad English that would not trespass on but cohabit with the bad English of other persecuted or marginalized people? Minor Feelings, among so many other things, is an argument for a literature, or a way of life, that would acknowledge a shared “unmastering” of English—“queer it, twerk it, hack it, Calibanize it.”

Brian Dillon’s essay collection In Pieces will be published in May by Sternberg Press.