Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Ottessa Moshfegh’s novel steps into the land of Nod (and Nembutals).

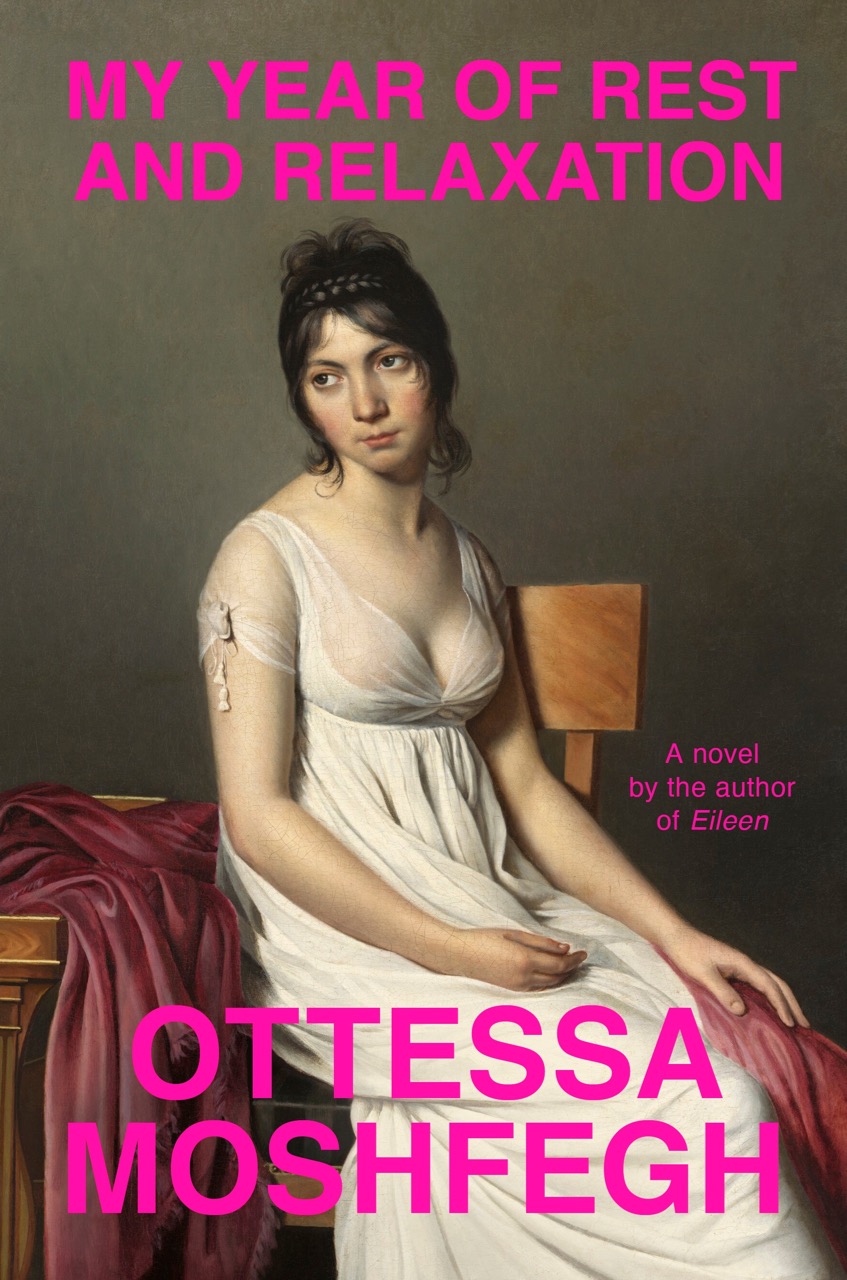

My Year of Rest and Relaxation, by Ottessa Moshfegh, Penguin Press,

289 pages, $26

• • •

“My nature is not to feel thrilled at being alive.” Interviewed by The Atlantic early in 2017, the novelist Ottessa Moshfegh made it deadpan clear she writes from intimate experience about the emotional rigors to which she subjects her characters. Depression, addiction, eating disorders, generalized feelings of entrapment and existential ennui: these have all featured in her fiction. In McGlue (2014), Moshfegh’s first novel, a man is locked up for the murder of his best friend, but does not remember committing the crime. The narrator of her second book, Eileen (2015), has been stuck in a perverse, isolating ménage with her alcoholic father. Her new novel My Year of Rest and Relaxation, Moshfegh told The Atlantic, is “a book about putting yourself to sleep in an effort to heal. But it’s also a book about waking up, and what that feels like: intolerable, but also absolutely beautiful.”

We’ll come back to beauty, and tolerance. This is certainly a book about sleep, if that is the word for the narcotized void into which Moshfegh’s anonymous protagonist slips on almost every other page. Rarely has a novel’s narrator felt less alive, less alert, less present in her own tale even as it spins. She’s not a narcoleptic, but the elective opposite of an insomniac—“I was more of a somniac. A somnophile.” Her languid tumbles are performed with the aid of a numbing pharmaceutical array; it is hard to exaggerate how many sentences in this book run something like: “So I filled prescriptions for things like Neuroproxin, Maxiphenphen, Valdignore, and Silencior and threw them into the mix now and then, but mostly I took sleeping aids in large doses, and supplemented them with Seconols or Nembutals when I was irritable, Valiums or Libriums when I suspected that I was sad, and Placidyls or Noctecs or Miltowns when I suspected I was lonely.”

The first four drugs in that list are made up, which ought to give us pause about the narrator’s reliability, but her pain is plausible enough. It is 2000, she’s twenty-seven, and she has a lot of brittle things going for her beyond youth, looks, and apparently bottomless funds: a degree from Columbia, an apartment in Manhattan, an intermittent boyfriend named Trevor, and till recently a job at a Chelsea gallery: “I was the bitch who sat behind a desk and ignored you when you walked into the gallery.” But Trevor is a self-regarding asshole, she’s been fired by the gallery for sleeping all the time, and life has shrunk to the apartment and a nearby bodega. She’s living in the affectless aftermath of her parents’ proximate deaths: her father was “eaten alive by cancer,” her mother followed weeks later with an overdose of drugs and alcohol. Try as she might, their daughter can summon no feelings about their deaths, nor about the mortal illness of her best friend Reva’s mother. All she wants to do is sleep.

You could not say that My Life of Rest and Relaxation exactly unfolds, let alone progresses, from its premise of blocked mourning and stymied emotion: any more, that is, than the narrator herself. Instead Moshfegh gives us with amazing narrative blankness—page after page, month by month, chapter upon chapter—the frictionless feeling of the depressive’s days unspooling, dissolving. “The goal for most days was to get to a point where I could drift off easily, and come to without being startled.” Reluctantly lucid, or something like it, she shuffles back and forth to the bodega, visits her criminally enabling and clearly mad doctor, fails to sympathize with Reva’s forthcoming orphanhood, phones Trevor at five a.m., and settles down to a lot of mostly awful movies on VHS. “I watched The World According to Garp and Star-gate and A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors and Moonstruck and Flashdance, then Dirty Dancing and Ghost, then Pretty Woman.” Sometimes she blacks out for days on the wrong (or right) prescription, and wakes not knowing where she’s been. Sometimes the reader feels the same.

Moshfegh’s portrait of her shallow (and shamelessly unlikeable) character’s psychic slump is at once relentless, dismal, and quite absurd. There are nice comic details in My Year of Rest and Relaxation, such as a gallery boss’s rage at too-clicky pens, and mordant set pieces like Reva’s mother’s funeral. But there is also at work here a philosophical comedy of intense boredom and pointless repetition. The narrator sneers at dudes reading Nietzsche on the subway, but she has become a cartoon instance of eternal return. She’s convinced, however, that if she can burrow even further into the void, she will emerge on the other side, if not brightened then at least, and at last, able to feel. The intensification of her project is effected by an artist called Ping Xi, who wants to paint and film her while she sleeps for three days at a time.

By this late point in the novel, all but the drowsiest readers, if it hasn’t struck them on the first page, will have noticed that Moshfegh’s narrative is edging toward September 11, 2001. Trevor and Reva both work at the World Trade Center. Will the protagonist even be awake on that day? More to the point: Will she be able to stay awake, face down catastrophe without recourse to stumbling detachment and total darkness again? What can a person tolerate, unconsoled by cheap movies or expensive drugs? And is there at the last, in extremis, while we’re actually or metaphorically falling—in the final pages of the book, the narrator swaps trashy films for 9/11 footage—something like beauty? The answers given by My Year of Rest and Relaxation are ambiguous, perhaps because (as in life) it is unclear what would constitute a clear look at disaster in the first place. At least, that seems the implication of this comically enervated novel’s ending, which comes up fast to meet us after all the longueurs that have gone before.

Brian Dillon’s Essayism: On Form, Feeling & Nonfiction is published by New York Review Books in September. He is working on a novel and a book about sentences.