Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Fear of the anacoluthon: Lydia Davis translates the Dutch writer

A. L. Snijders.

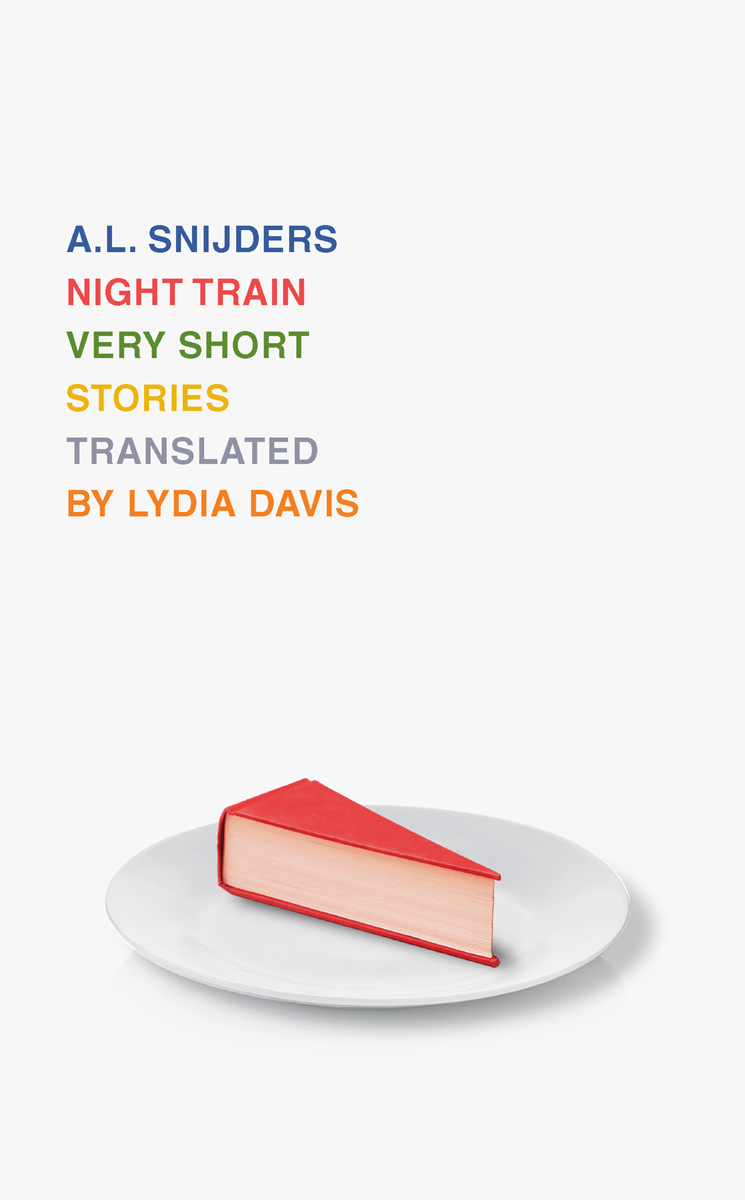

Night Train: Very Short Stories, by A. L. Snijders, translated by

Lydia Davis, New Directions, 150 pages, $14.95

• • •

The Dutch writer A. L. Snijders was born in 1937 to a bourgeois Catholic family in Amsterdam—we get brief glimpses of this milieu in a few of the stories selected and translated by Lydia Davis in Night Train. (Ninety stories in all: the longest two pages, the shortest just five lines.) Snijders had ambitions to become an artist, but instead for many years taught at a police academy; in 1971 he moved with his wife and children to rural Achterhoek: his brief and diverse fictions are populated by animals and scored in their small way to the rhythms of a quiet country life. Since the 1980s Snijders had been a widely read newspaper columnist—for a long time he insisted on publishing in his local free paper as well as the national press—but that workaday writerly calling doesn’t capture the strangeness of narrative and tone he smuggles onto the page and latterly (in his eighties) into weekly readings on the radio.

But first: his translator, and her typically sedulous but eccentric presentation of Snijders’s work. In a preface titled “The Very Short Stories of A. L. Snijders,” Davis writes that in 2011 she visited Amsterdam for the first time, on the occasion of a Dutch translation of her own very svelte stories and left feeling she must translate some small example of Dutch fiction into English. Snijders was suggested, and she set to work on “Years,” a piece composed of five compact paragraphs in which the author (or his fictional stand-in) revisits a street where, as a child, his mother once fell from a window.

That’s to say, Davis started translating “Years” while barely knowing a word of Dutch. “I chose to read it first without a dictionary, since I found I was more deeply inside it that way, figuring out what the words meant from the context, and enjoyed it more.” Aside from the ruinous envy a reader may feel at this point, Davis’s essay is a fascinating insight into her process. (Even the celebrated translator of Proust and Flaubert is apparently prey to “false friends” in a new language.) Her dictionary-free method soon gave way to a more informed approach, deepening her knowledge of the language and pursuing curios of Dutch culture: “reviewing the hours and stock of a chain store in Rotterdam or the specifications of different brands of tile stoves.” Davis’s notes to the stories give us more such detail, including derivations of Dutch idioms and sayings. But curiously she doesn’t address at any length a striking feature of Snijders’s stories: so many of them turn on certain small linguistic oddities or ambiguities.

Consider the page-long “Frisians,” in which at the outset the narrator is eating “an Italian meal with a Scottish drummer in the city of Groningen.” The drummer’s Dutch is good, but when stuck for a word or phrase he sometimes “has recourse to the Scots, as a result of which there arises a language which strict grammarians would scorn but which to my great pleasure they can’t prevent.” The narrator tells the Scotsman an anecdote about getting into an argument with a woman in the northern Dutch region of Friesland who would only speak Frisian to the monoglot visitor and complained about the dominance of the Dutch tongue. Another woman commented ruefully on the Friesland patriot: “There are Frisians and there are Frisians.” This is at the more mundane end of Snijders’s self-consciousness about language. In “Shoe” he writes about his own literary laconism. As a school and university student he was hampered by the narrowness of his writing style: “What annoyed me above all was that I could not write long sentences. I developed a fear of the anacoluthon.” His writing, a teacher told him, was “too lapidary.” But in time he learned that brevity could be a matter of deliberate technique (“few conjunctions, little explanation”) and had about it a certain substantiality—his stories, including the one in which he says this, feel dense and airy at the same time, like one of those superlight solids invented by NASA.

There are the pieces that seem like simple, almost sentimental, reflections on nature, such as “Seagulls,” with its fleeting snapshot of leaves, chickens, worms; and the narrator’s first encounter with a fox, in “Fox.” Spare but touching glimpses of family life and its tiny but aching realizations; meditations on age and wisdom, as if Snijders were a nineteenth-century diarist or miniaturist man of letters—some of these fragments read as though excised from a longer, more properly literary, body of work. As an adept of reduced forms, Snijders is quite without the melancholy of Robert Walser, but neither does he craft the crystalline peculiarity of a contemporary short-story writer like Diane Williams. Sometimes there’s a wealth of literary reference (Stevie Smith, John Fante, Jules Renard) and sometimes not at all. Davis points out that in structure and pacing Snijders’s works vary greatly; perhaps the most notable thing they have in common is a tendency for characters to appear from the distant past, wandering back into the octogenarian’s small but skewing orbit.

How much of this is Snijders, and how much fictional? Davis tells us that at first she believed, or wanted to believe, that here was a kind of autofiction, and one can quite see how the form of the journalistic column or essayistic feuilleton might encourage that assumption. Snijders told Davis that just two hundred out of his three thousand (and counting) stories were based wholly in fact. Occasionally he plays with the possibilities: in “Story (3)” he, whoever “he” is, meets a man on a train who tells him he has long been hopelessly in love with his neighbor’s wife. “I know it, I say, it’s a story by Anton Chekhov, you’re telling me a story by someone else.” The lovelorn man also knows the story: “Do you think Chekhov invented it? With writers, you never know, I say.” Elsewhere Snijders reproduces a tiny tale culled from a newspaper article from twenty years before, gives us the bones of the story and then, in a king of bravura obviousness, quotes the original article. It’s a technique that of course recalls Davis’s own appropriation of found scraps of speech and writing—while resembling, even in her translation, Davis’s fiction in no stylistic, tonal, or formal fashion.

Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence and Essayism are published by New York Review Books. He is working on Affinities, a book about images.