Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

In a book of art essays, Giorgio Agamben steps into his rumination room.

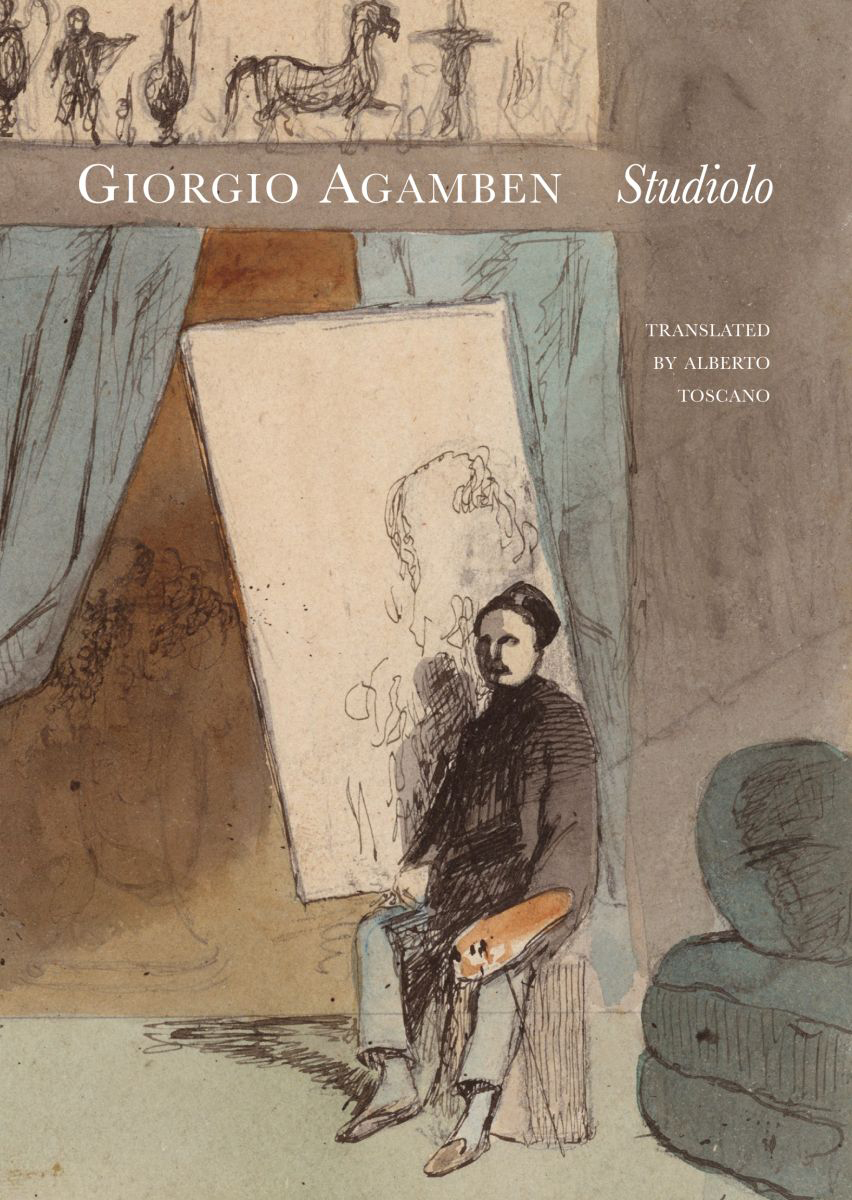

Studiolo, by Giorgio Agamben, translated by Alberto Toscano,

Seagull Books, 164 pages, $25

• • •

The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben—sadly best known right now for his extravagant pronouncements against pandemic restrictions—has long been adept at short forms: essay, gloss, note, or scholium. His books, especially those on art, literature, and aesthetics, have tended to be agglomerations of these fragments; a work such as the multivolume Homo Sacer, on the logic of biopolitical power, stands out for its sustained argument and scholarly scope. Agamben’s latest book is at the svelter end of his corpus, and contains twenty-one brief essays on twenty-one works of art. Studiolo takes its title from a private space devoted to intellectual or aesthetic contemplation. The aristocratic studiolo of fifteenth-century Italy was something like a refined, wood-paneled version of the northern-European Wunderkammer or cabinet of curiosities: a chamber, as Agamben put it in an earlier essay, “in which the scholar could measure at every moment the boundaries of the universe.”

In Studiolo, Agamben imagines a room of his own, secluded and fantastical, but giving widely onto views of art history, metaphysical thought, and religious feeling. This imaginary museum includes several painted scenes from classical literature; in Titian’s Flaying of Marsyas, Agamben discerns “an allegory of the abyssal difficulty of the painter’s imagination.” Christian iconography features heavily, but Agamben is interested in precisely those moments when it stops being iconic and starts to look too much like the world: he examines Dostoevsky’s passages in The Idiot on Hans Holbein’s faith-effacing Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb. (There is no mention in this essay of Julia Kristeva’s well-known reading of the novel and the painting in her book Black Sun—not an untypical omission on Agamben’s part.) A painting’s mundane details may acquire extraordinary significance, as in Agamben’s rumination on a pair of clogs in Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait: “Brought up close in this manner, the thing exhibits but does not communicate itself: it is, in other words, obscene. That is, it cannot be painted.”

The very possibility of art itself is this small book’s large theme; many of Agamben’s analyses of his favored artworks or images turn on questions about the limits of painting or sculpture, as if his aesthetic ideal is a space in which the work of art would sublime itself out of existence before his gaze. Perhaps this has already happened, or never ceased happening. Titian’s Nymph and Shepherd, Agamben tells us, is “almost a farewell to painting.” An untitled sculpture by Cy Twombly, featuring a quotation from Rilke, embodies beauty at the moment of collapse. And The Night by Isabel Quintanilla convinces Agamben that “Painting can represent (or better, present) reality only if it can become the painting of painting.” It seems that in the philosopher’s private study, art is always coming to an end, or self-consciously framing itself, denoting its own limits.

These are not new themes for Agamben. The argument of his essay on the Wunderkammer is partly that its historical successor, the modern art gallery or museum, stages the end of art’s unity and its purchase on the world outside; it’s henceforth a gallery-bound art about art, for better and worse. As a young scholar and critic in the 1970s, researching at the Warburg Institute in London, Agamben was a daring and learned interpreter of images. My twenty-five-year-old copy of his Stanzas (first published in Italian in 1977) is falling to pieces; I’ve gone back many times to its magnificent essays on Dürer’s Melencolia I, on the proto-Surrealist illustrations of Grandville, on medieval depictions of Pygmalion and his living statue. For a long time, it was possible to be thrilled by the alacrity with which Agamben moved between images or objects (the nativity crib, the films of Pasolini) and conclusions about metaphysics or politics.

Sad to relate, there is next to nothing of scholarly discovery or conceptual invention in Studiolo. Nor any late-style turn to a more personal tone, such as the premise of the book might signal. This is definitely not Agamben’s Camera Lucida—if only. Instead, it reads as both crankish and arbitrary, insisting that the works discussed are all about the numinous or unsayable, and at the same time refusing to countenance very much work that isn’t in the lineage of painterly realism. It’s frankly as if the artistic convulsions of the twentieth century never happened; Agamben’s choices among modern artists are mostly of a neo- or ultra-realist stripe. In the case of Gianfranco Ferroni’s painting Analysis of a Floor, Milan—bare boards, detritus, wine bottle—the work yields less-than-stunning insights: “according to the ancient aphorism, painting here is truly ‘a silent poetry.’” In fact, there is usually a venerable text for Agamben to refer to, not only as poetic or mythic source for a painting’s subject, but seemingly as a guarantee of the seriousness of his own gaze. There’s always a passage in Aristotle, Dante, or Diderot to explain what he is seeing.

Is this all we want from a philosopher looking at art? The series or pattern, collection or constellation: it’s a dream assignment (or self-assignment) for any writer with sufficient ego and curiosity. Reading Studiolo, I kept being reminded of books that have done so much more with the conceit of placing one image after another, with attendant caption or comment. Books such as David Campany’s On Photographs; or Looking at Pictures, a compendium of Robert Walser’s short writings on art, put together by Susan Bernofsky and Christine Burgin. Imagine what a writer like Mary Ann Caws or Marina Warner might have done with a similar brief: to corral a lifetime’s looking and thinking into the notional space of the studiolo or the cabinet of wonder. The purpose of the exercise would surely be to surprise yourself, to set aside the consolations of prior knowledge and reference points, to find out what the work itself knows. Everything, in other words, that Agamben has failed or disdained to do in Studiolo.

Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence and Essayism are published by New York Review Books. He is working on Affinities, a book about images.