Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Workplace satire meets outer-space allegory in a Danish writer’s

second novel.

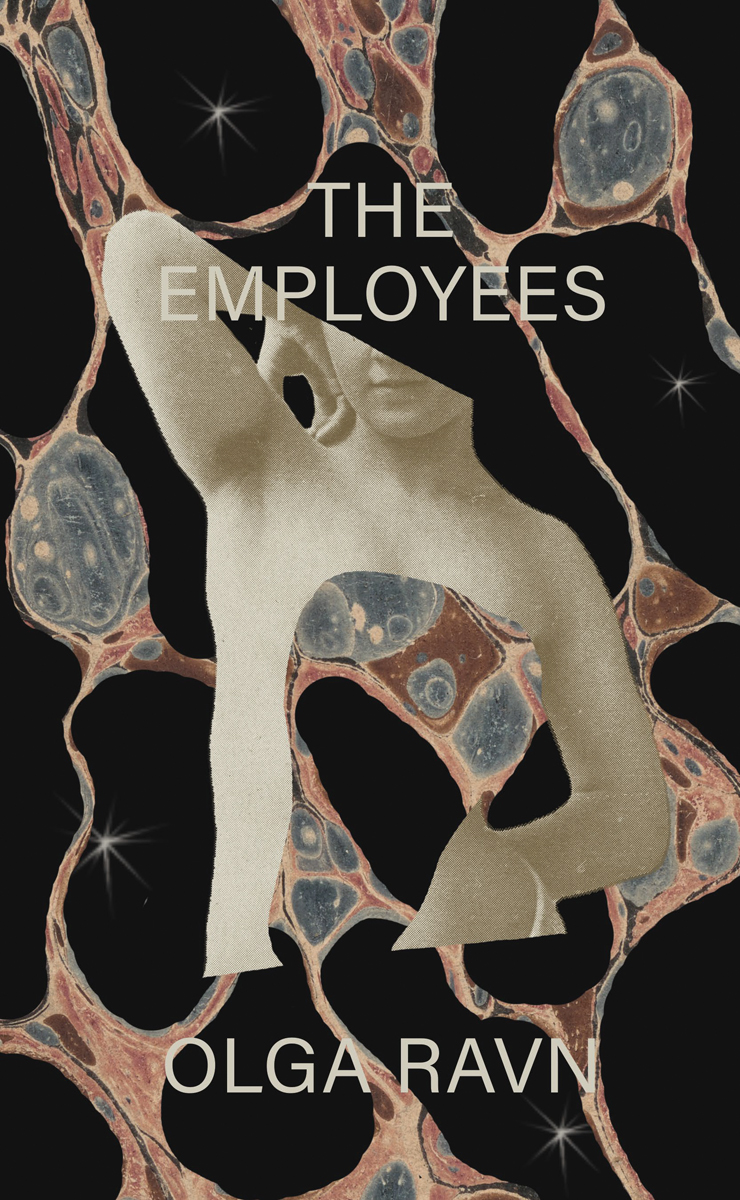

The Employees, by Olga Ravn, translated by Martin Aitken, New Directions, 125 pages, $19.95

• • •

“I want more life, fucker!” says the replicant Roy Batty in Blade Runner (1982) before he destroys the corporate scientist who made him. “Fucker” becomes “father” in later cuts of the film—unfortunate literalism. A sci-fi staple: if you invent a race of near-humanoid slaves, in time they will turn on you with vengeful intent, not to mention awkward existential questions. So it transpires in Olga Ravn’s laconic, discomposing The Employees. (It is the Danish writer’s second novel—she is also a poet, critic, and translator—and was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize in 2021.) Ravn’s plot depends too on the stock motif of a specimen-gathering spacecraft a long way from home, controls set for catastrophe. In brief numbered statements delivered by the human and nonhuman crew of the Six Thousand Ship to a shadowy committee, Ravn seeds her narrative with direct and allegorical reflections on transhumanism, disappearing nature, and the ambiguities of being embodied.

As the title implies, The Employees is at the same time a satire of the contemporary workplace; I half expected a big reveal to the effect that the action was really taking place in an all-too-earthly Amazon warehouse. An italicized framing narrator tells us in blank managerial jargon that the committee’s interviews have taken place over eighteen months and are concerned with “reduction or enhancement of performance, task-related understanding, and the acquisition of new knowledge and skills.” A sort of class structure exists between human workers and their humanoid counterparts, except the hierarchy is unclear. Which is the more precarious and temporary position? Which the more authentic? Each group seems at times to envy the other, even as they remain mutually enigmatic. What can it mean, asks a baffled humanoid when reporting a conversation with a human coworker, to believe that “a person is more than just their work?”

As for what this “work” entails, the crew is in charge of (or cares for) nineteen “objects” collected on the pastoral green planet New Discovery. Are these things alive? Sentient? Happy or sad? Interviewees report mostly details and impressions, gleaned from their visits to the rooms where the objects are kept, or imprisoned. One of the captives, decorated with long cords “spun from blue and silver fibers,” seems to be female, and has laid an egg. Another resembles a gift, wrapped in pink ribbon. The crew give unofficial names to the objects (or beings): the Dog, the Reverse Strap-On, the Half-Naked Bean. Each has its own fragrance, strangely attractive to the workers who tend it, one of whom would like permission to hold an object—as if it were a child, or the pitiful “half kitten, half lamb” in Kafka’s story “A Crossbreed.”

“You’d probably say it was a small world, but not if you have to clean it,” declares another employee about the spaces that contain the objects. The sentence paraphrases the title of a work by Barbara Kruger, who is not the only artist to have inspired The Employees. A slightly vague dedication page doesn’t quite say it: the novel was written in 2018 to accompany an exhibition by the Danish artist Lea Guldditte Hestelund. Ravn’s objects are based on sculptural elements in an installation titled Consumed Future Spewed Up as Present: an array of fringed leather halters or harnesses, a selection of more or less organic-looking marble entities, colorfully spray-painted or veined. As shown at the Overgaden art institute in Copenhagen, the original sculptures resembled torsos, organs, or tumors—offcuts from a future species that might in fact be our own. At one level, The Employees simply imagines a context for these artifacts, and for those who look at them: “Am I human or humanoid? Have I been dreamt into being?”

In Hestelund’s show, The Employees was a leather-bound volume presented as another work or aspect of the installation. Such relations between art and fiction are gifts to both artist and writer. The artist acquires a text that is sympathetic to her themes or forms but doesn’t imprison the things themselves in explication or critique. The writer gets to invent as she pleases, but with the grounding (or maybe, in this case, unsettling) knowledge that there are real objects to be described, forms and textures that demand their due, actual intentions to be divined—or ignored. Which considerations also mean this type of writing rarely escapes the airless precincts of its occasion or commission to become a “proper” novel, whatever that may be.

Its art-world origins are instructive, but Ravn’s book has a sickly, anxious energy all its own. Though the crew’s testimony is plainly stated, it’s also quite opaque: we sometimes know who is speaking (the first officer, say, or the ship’s funeral director) and at times can be sure that person is human. We never know the motives of a Dr. Lund, who seems to have invented the humanoids and to be directing the unstated “program” of the Six Thousand Ship. Ravn carefully rations plot details: the stirrings of incipient revolt, a nostalgia for Earth that has overtaken the humans, the disappearing authority of Lund and maybe also of the committee’s inquisitors. The testimonial format has to do most of the labor of characterization, plot, and suggestive imagery—it’s a feat to achieve this in short fragments without too much overt thematic semaphore.

In the end, you come away from The Employees with a series of unnerving visual moments in mind, from which something has been excised or obscured, like a migrainous blind spot or scotoma. What is the “add-on” that some of the humans describe being attached to their bodies? When they retreat to their bunk rooms to commune with a “child hologram,” what does this heartbreaking vision from the earthly past actually look like? The novel is by turns queasily exact about what is seen—skin pitted like pomegranate, an object’s furrows oozing some nameless balm—and willfully obscure. Ambiguity is everything: “I don’t know if I’m human anymore. Am I human? Does it say in your files what I am?”

Brian Dillon’s Essayism and Suppose a Sentence are published by New York Review Books. Affinities, a book about images, will be published in 2023.