Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Is Anne Carson nice or happy? Right or wrong question?

Wrong Norma, by Anne Carson, New Directions, 191 pages, $17.95

• • •

In May 2017, the New Yorker published a prose poem by Anne Carson titled “Saturday Night as an Adult.” It’s a short, incidental-seeming paragraph, but it’s also a small masterpiece of observation and phrasing, describing a mundane episode freighted and fraught with life-size disappointment. The speaker recounts a dinner date between two couples: “We really want them to like us. We want it to go well. We overdress. They are narrow people, art people, offhand, linens.” The restaurant is noisy, awkwardness follows, and then despair: “We thought we’d be Nick and Nora, not their blurred friends in greatcoats. We cover our ears inside our souls.” The tragicomic poem appears again in Carson’s new collection, Wrong Norma, but in the meantime, it has had an odd, dispiriting celebrity. In the summer of 2023, the journalist Hannah Williams tweeted a screenshot of “Saturday Night as an Adult”—Think about this a lot—and seemingly broke certain brains. What a mean and miserable woman this Carson was with her little—what? Story? Essay? Anecdote? Wow that’s crazy has the author ever thought about letting joy into their life.

Whether Anne Carson is relatable, whether she is nice, or happy: these are not questions that I suppose previously troubled admirers of her poetry’s formal and stylistic adventures, her often giddy erudition (which draws on her career as scholar and teacher of classical literature), or the emotional intensity with which she may treat her own biography or gilded and bloody lives from Greek mythology. To reduce such a complex and seriously playful writer to a kind of late-pandemic sad Karen, you would need a perfectly literal cast of mind, no? And yet. Although the angry Twitter innocents got her all wrong by reading “Saturday Night as an Adult” as direct personal gripe, there is a sense that over the past decade her work has grown more accessible. (I blinked and missed her in last week’s New Yorker, a piece this time labeled “fiction.”) Perhaps it’s inevitable when you have won all the prizes and become a source from which the rest of us plunder epigraphs. Wrong Norma, which is Carson’s first original—whatever that means—work since Float in 2016, gathers poems of widely varying intricacy, weight, and friendliness.

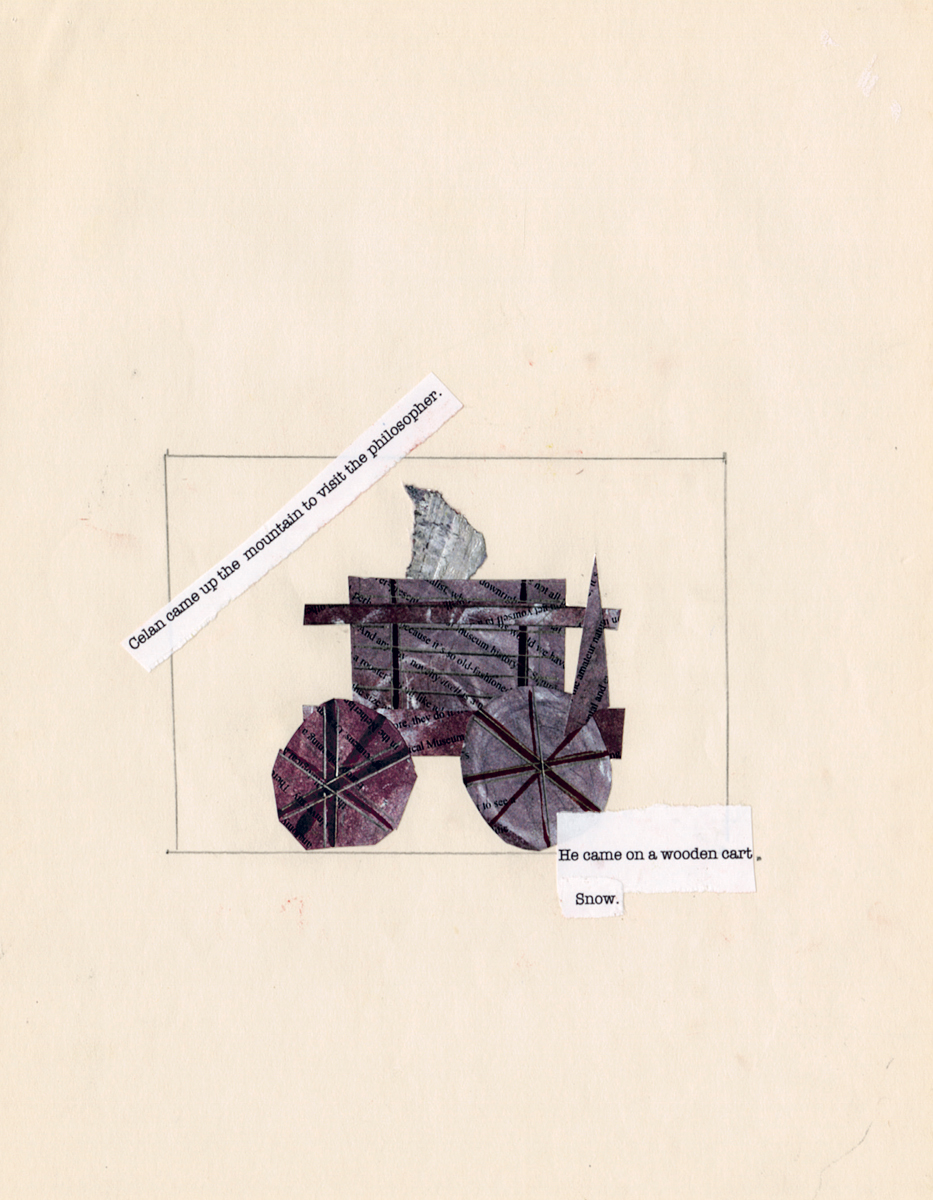

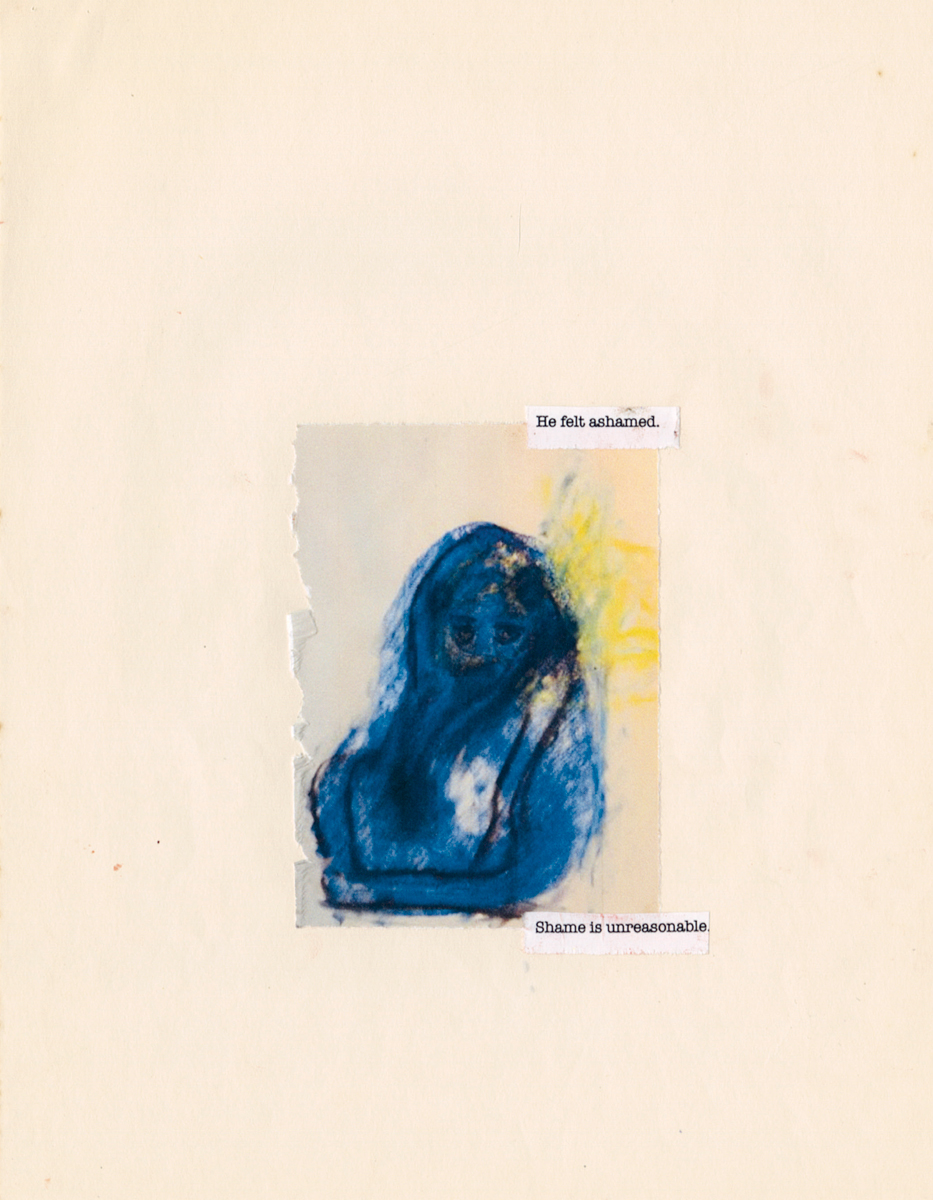

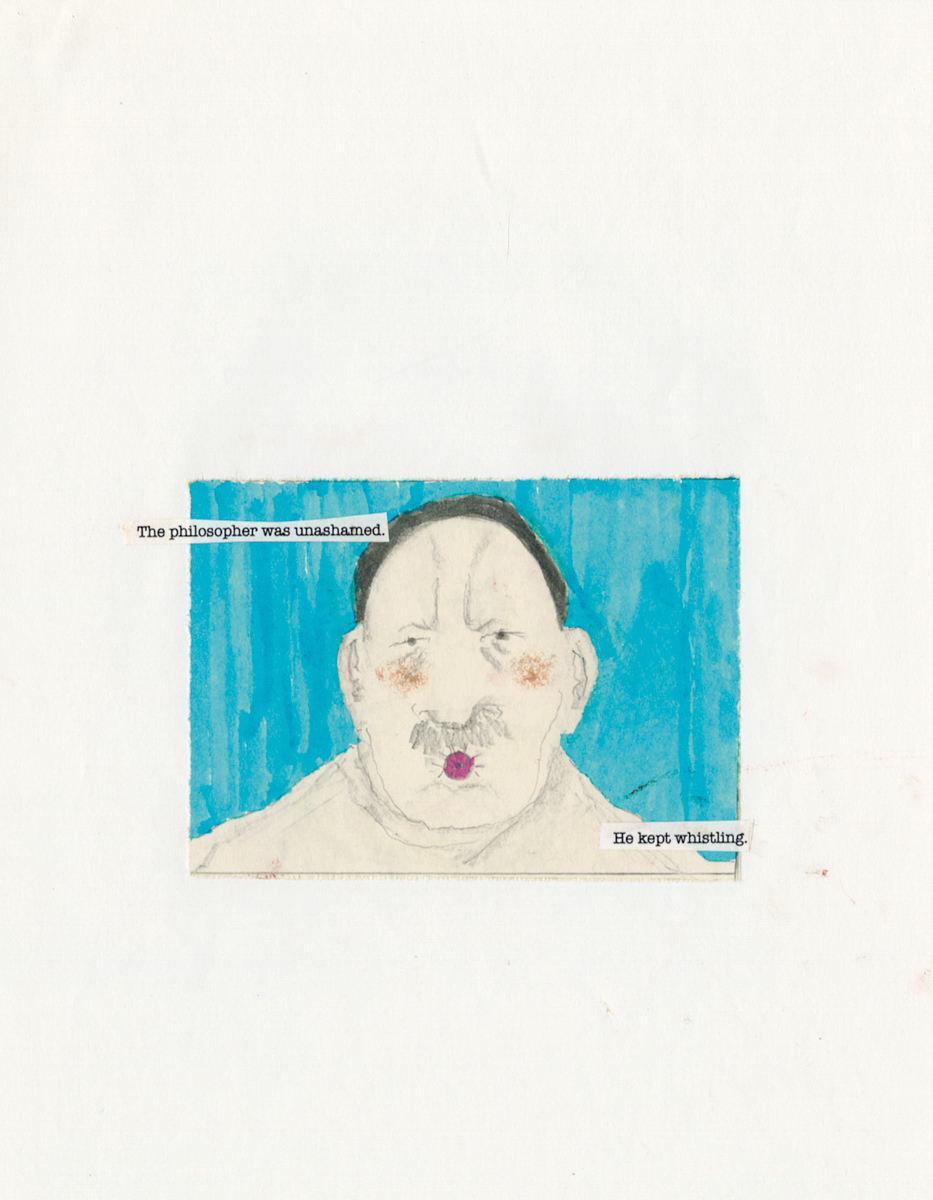

From Wrong Norma. Courtesy New Directions.

There are twenty-five pieces here, including “Todtnauberg,” a suite of drawings and collaged text about Paul Celan’s visit to Martin Heidegger’s mountain hut in 1966. (A series of more opaque images and poetic collages appears between poems.) Carson is no less learned or referential in Wrong Norma than in earlier works, such as “The Glass Essay” (1994), with its invocations of Emily Brontë; Autobiography of Red (1998), which recasts the myth of Heracles and Geryon; or The Beauty of the Husband (2001)—the story of a marriage bound up with reflections on John Keats, truth, and beauty. Reprinted in Wrong Norma is “Poverty Remix (Sestina),” first published in 2018, and its eight prose appendices. In it, Carson reflects on the poetry of Hipponax, who in the late sixth century BCE distinguished himself from others by writing about the poor. (Hipponax also stood out on account of his physical deformities. When ridiculed for these, Carson tells us, “he responded with songs so bitter his mockers killed themselves.”) “Poverty Remix (Sestina)” is a poem about shame felt by unhoused people, the speaker’s shame in her dealings with them, and rituals surrounding the ancient figure of the scapegoat—“Beat him with fig branches seven times on the genitals.” In the appendices, there are short disquisitions on the etymology of the Greek word pharmakos (both poison and cure), on dirt and purification (“Who is pure?”), on William Wordsworth’s habits of stealing lines from his sister Dorothy and making his guests pay for their supper. Carson’s six numbered stanzas, meanwhile, throw ancient scapegoating impulses into stark proximity with modern homelessness: “Poverty is a scapegoat. / We drive them out!”

From Wrong Norma. Courtesy New Directions.

Other pieces in this collection have a looser and seemingly more personal mode of address. Lecture, essay, short talk: these are the forms, or perhaps merely the labels, by which Carson has sought to differentiate between what are all essentially prose poems. This persistent nomenclature has become for longtime readers a near-invisible terminology; the mix of verse and prose, lyric voice and scholarly style—all of this is easily accepted. Which means it can feel a little excessive or uneasy when a text such as “Lecture on the History of Skywriting” signals its conceit (a lecture by the sky!) a little too obviously: “This is a lecture on skywriting. / Mine. / I am the sky. / Here follows a brief history of my life as a writer.” But the poem itself is beguiling. The firmament recalls meetings with classical nymphs, conversations with Christopher Hitchens, interviews with pebbles and small rocks, and problems ensuing from an 1802 lecture by cloud-study pioneer Luke Howard, to whom we owe the division into cumulus, stratus, and cirrus, as well as blurry intermediate conditions. According to Carson’s sky, all above is indistinct and protean, and Howard quite wrong. It (she? he?) is exhausted “hauling myself around the upper air in cloud masquerade.”

Is the sky’s complaint also a threnody for a dying earth? Or is the whole thing starting to sound whimsical? There are poems here that can seem as if Carson has aimed for the askew poise of a perfect story by Lydia Davis or Diane Williams, and slightly missed. It is possible “Saturday Night as an Adult” is one of those. “Dear Krito” is a “letter from Sokrates in gaol” (archaic spellings Carson’s own), in which the philosopher name-checks Iggy Pop and Bob Dylan and gripes about Plato: “he’ll go on about swans or gymnastics or who knows what.”

From Wrong Norma. Courtesy New Directions.

But alongside such genial poetic conceits there are also works here of abiding strangeness and profundity. The opening poem, “1 = 1,” returns us to a watery imaginary that has been present in Carson’s work from the start. Lake-swimming at dawn, with Keatsian undertow: “Perhaps involved is that commonplace struggle to know beauty, to know beauty exactly, to put oneself right in its path, to be in the perfect place to hear the nightingale sing, see the groom kiss the bride, clock the comet.” But it’s also a poem about a darker current, pulling boat-bound refugees to their deaths—passengers, and passed over. Carson can seem a rarefied, scholarly, or forbidding poet; but such moments as this, and the lament of the sky, inseparable from erudition and wit, connect her work to the world in startling ways.

Brian Dillon’s Affinities, Suppose a Sentence, and Essayism are published by New York Review Books. He is working on Ambivalence, a book about aesthetic education.